Despite impressive achievements in schooling and microfinance for women, Bangladesh still has low female labour force participation. Data from rural Bangladesh suggests that strengthening agro-processing may increase female employment and productivity.

The success story of Bangladesh in advancing opportunities for women is well known. By 2015, Bangladesh became one of the few countries to achieve gender parity in school enrollment. There are presently more girls than boys attending Bangladeshi secondary schools, and more than 30 million women in Bangladesh are clients of microcredit organisations. These advancements should result in women accessing productive market opportunities and achieving financial independence, but this is not the case. Bangladesh still suffers from low female labour force participation and a virtual absence of women entrepreneurs. While these issues are prevalent across the country, I focus specifically in this blog on rural women since barriers like social stigma against women are more prevalent in rural areas.

Female entrepreneurship in rural Bangladesh

Only 439,000, around 7.5% of 5.8 million rural enterprises in Bangladesh, are owned by women. Moreover, these enterprises are concentrated in tailoring, textiles, and bamboo and cane products – sectors which are typically not associated with high-growth opportunities. This is reflected in the small size of these enterprises. Women-owned enterprises in rural Bangladesh have 0.84 paid full-time employees while men-owned enterprises have 1.55 – almost double. In fact, 64% of women-owned enterprises do not have any full-time employees at all, indicating that these are small personal ventures rather than organised businesses.

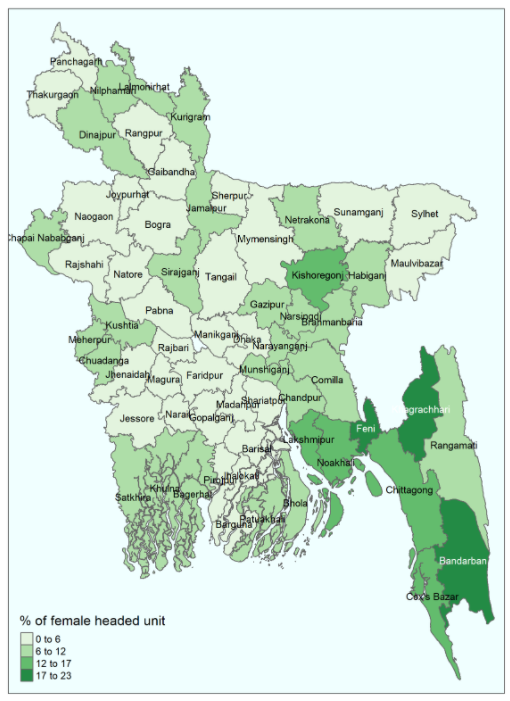

A spatial analysis of female-owned enterprises reveals an interesting trend. Among the five districts with the highest proportion of female-owned enterprises, two are from Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) region (Bandarban and Khagrachari with 21% and 17%, respectively)1. This region has suffered from political violence and usually lags behind the rest of the country in socio-economic indicators, but ranks surprisingly highly in proportion of female-owned enterprises. This may be because CHT is home to various ethnic minorities with a female-headed social structure. If so, then it follows that the social preference of men as breadwinners over women has a role to play in the stymied growth of entrepreneurship in rural areas in Bangladesh. Unfortunately, the high proportion of female entrepreneurs in CHT does not make a significant mark in the national landscape as the economically struggling area has very few enterprises relative to growth centres like Dhaka or Chattogram.

Figure 1: Percentage of female-owned enterprises by district

Labour force participation and voluntary work

The impressive schooling rate of women in Bangladesh is yet to convert into labour force participation (LFP). The LFP rate for Bangladeshi women stood at around 38% pre-pandemic compared to 84% for men. Low female LFP is endemic across major South Asian nations, with India and Pakistan lagging even further behind Bangladesh. However, Bangladesh compares poorly to the more equitable Southeast Asian nations like Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia – countries that have had female LFP at around 50% or more since 1990, and achieved relatively fast economic growth.

Another damaging trend in rural Bangladesh is the prevalence of voluntary work among rural women. Only 6.5% of all rural workers work as unpaid or voluntary family workers, but the number increases to 18% for women. It is likely women’s work goes unrecognised because of the tendency to lump women’s contribution to agriculture into household work. Analysis of the Labour Force Survey 2016-17 shows crop and animal production as the largest source of employment for women workers. However, most women working in these sectors are either working owners or non-paid family workers, with only 6% of them working as paid employees. Within the crop and animal sector, cattle and dairy is a large sub-sector comprising 5.6 million women. However, a cursory look at FAOStat data shows productivity in this sector to be far lower than the global average, and lower than neighbouring countries like India and Pakistan. This may be one of the reasons for the low frequency of paid employment in the sector.

Paid employment for female, even in rural areas, comes mostly from the Ready-Made Garments (RMG) industry, with 42% of all rural full-time jobholders working in RMG and its value chains, according to BEC 2013 data. Such dependence on a single sector does not bode well for female employment in the long-run. Importantly, the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics reported in 2019 that the proportion of female worker in RMG declined by almost 11% since 2013. This reiterates the importance of increasing female employment and productivity in other sectors.

Policy implications

Bangladesh has made tremendous strides towards female empowerment in the last three decades. However, advances in schooling or fertility rates are yet to fully translate into increased productivity. Microcredit organisations have almost universal access, but to realise their full potential, they require market integration of sectors where women work. A sector-specific approach may help the country achieve greater female empowerment. Based on the analysis presented above, expedient government focus is needed on the cattle, dairy, and poultry sector. Despite numerous people working in these sectors, Bangladesh still spent more than US$350 million on importing milk concentrates alone in 2019. In general, agro-processing should be a focus area of the government. A successful agro-processing industry ensures fair prices for farmers, thus helping the rural economy in general and women workers specifically, given their ubiquitous role in agriculture. The Sirajganj and Natore Economic Zones, which are currently under construction, will play a vital role in this regard due to their proximity to agriculturally active and poverty-prone northern region of the country.

This article is part of our gender equality series.