Women's employment during the pandemic in Ghana: A tale of vulnerability and resilience

Women have traditionally been more vulnerable in the labour market, more underrepresented and the nature of their employment less secure. While the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures to contain it hit women's employment the hardest, they were also the more resilient and rebounded much faster than men.

Editor’s note: This article is part of our International Women’s Day campaign and is based on this IGC project.

The world celebrates International Women's Day this month. This year the celebration has been eclipsed by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the threats it poses to women, particularly in the labour market. As Mary Robinson observed, "the impacts of crises are never gender-neutral, and COVID-19 is no exception". A view corroborated by a recent study, which shows that unemployment is higher amongst women than men in the United States. Beyond the vulnerability, however, there lies a sheer resilience of women even in this crisis.

The employment situation of Ghanaian women has always been a major policy challenge. Educational attainment, traditional roles and occupational segregation by gender restrict women's access to the labour market in Ghana and elsewhere in Africa (Atieno, 2006; Baah-Boateng et al., 2013). As a result, a significantly larger proportion of women than men earn their living in vulnerable[1] (80 percent vs 65.4 percent) and informal employment (54.9 percent vs 54.1) (GSS 2016). The existing evidence suggests that low and unstable income with little or no social protection characterised women's employment than men's world of work before the pandemic (Baah-Boateng & Twum, 2019).

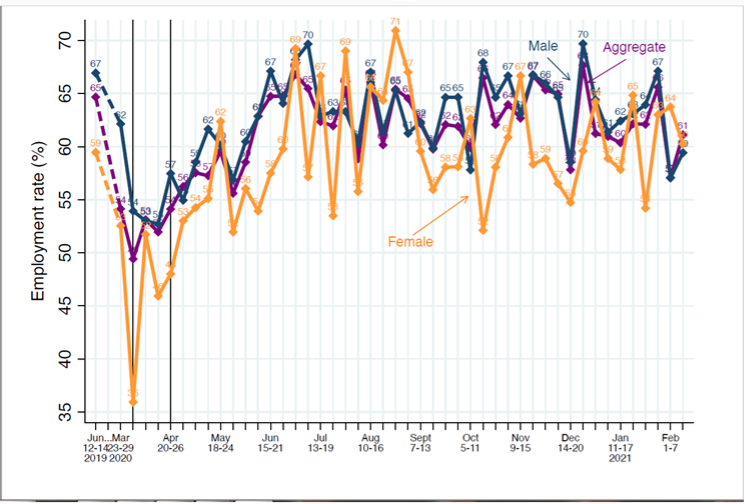

However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the policy measures instituted to contain it highlights the vulnerability of women's employment. For example, within the first week of the lockdown, women's employment rate dropped by 23 percentage points compared to the 13 percentage points drop amongst men. This is partly because the informal nature of women's employment requires that they have a day out in the market, which was disrupted during lockdown. Nonetheless, by the first week of February 2021, women's employment had fully rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, while men's employment still reels under the weights of the pandemic. This suggests that due to their low income and little or no social protection, women find innovative ways to return to work much earlier than men, on average.

Towards a data-driven policy response

In the wake of COVID-19, the government of Ghana rolled out a suite of measures, including lockdown of the economic hubs to stem the spread of the virus. Within weeks, however, it became apparent that these measures are not sustainable. As the President put it, it was impossible for the government to "… ignore the impact this lockdown is having on several constituencies of our nation, especially the informal workers who need to have a day out in the market to provide for their families."

To better inform policy response, IGC Ghana launched "the Economic Situation in Ghana" reports. Through this effort, high-frequency economic indicators were generated to help tailor policy measures to contain the pandemic and its impacts on livelihoods. The reports capture two main economic indicators: weekly employment and monthly electricity usage.

The employment data comes from an online survey of Accra and Kumasi's labour market activities. The first survey was conducted in June 2019, followed by a weekly survey from 23 March, 2020. The survey provides detailed and early signals about women's employment situation before, during, and after the lockdown.

Vulnerability of women's employment

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown, Ghanaian women were underrepresented in the labour market, as documented by the various Ghana Living Standard Surveys (GLSS7, GSS 2016). Consistent with these reports, we find that only 59% of women reported working for pay or profit during the past seven days, as of June 2019 (Figure 1). Men fare relatively better, with two-thirds having reported working.

Figure 1: Women's employment: Vulnerable but resilient

The data shows that employment rates were already declining well before the lockdown came into effect on 30 March 2020, with women's employment suffering the largest drop. By the first week of the lockdown, women's employment rate dropped significantly by 23 percentage points to 36 percent. The corresponding reduction in men's employment rate is 13 percentage points. Further, women's employment rate shows more fluctuations than the corresponding rate for men. Measured by standard deviations, women's employment fluctuates 3.6 times the volatility in men's employment (5.89 vs 1.64).

The sharp drop and the associated fluctuations in women employment relative to men are primarily driven by the larger proportion of women who earn their living in the vulnerable and informal sector (GSS 2016). These findings are consistent with the view that the lockdown had negative impacts, especially on "… the informal workers who need to have a day out in the market to provide for their families." An additional potential underlying reason is that women's employment is concentrated amongst heavily affected sectors such as hospitality, retail/wholesale, and education.

Vulnerable but resilient?

The above exposition suggests that women were in a disadvantaged position even before the first COVID-19 case was reported in Ghana. It suggests further that pandemic and the lockdown measures instituted to contain it affected women employment disproportionately relative to the rest of society.

Nonetheless, Figure 1 also reveals the sheer resilience of women's employment. For example, within the second week of the lockdown, women's employment had recovered by 16 percentage points following the initial drop, while men's employment rate suffered a further percentage dip. The pattern of rebound ran throughout the entire lockdown and post-lockdown periods. Furthermore, by the first week of February 2021, women's employment had fully recovered. However, men's employment rate is yet to attain its pre-pandemic levels.

A plausible reason for the relatively quicker rebound of women's employment lies chiefly in the need to "have a day out in the market". With no saving or social insurance to fall on (Baah-Boateng & Twum, 2019), women have to find innovative means to rebound quicker than men. An alternative explanation is that women work predominately in sectors that recovered earlier. However, this does not seem plausible. Apart from the retail/wholesale sector, hospitality and education are still reeling in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Policy pathways out of crisis should not be gender blind

The evidence implies that the pandemic and the measures to contain it hit women's employment the hardest. Yet, the subsequent labour market rebound owes much to the resilience of women. A clear policy implication is that the extent to which crisis, such as COVID-19, impact societies and how societies emerge from them hinge more on both the vulnerability and resilience of women. While this is consistent with the view that "the impacts of crises are never gender-neutral", it also suggests that the policy pathways out of crisis should not be gender blind.

The policy response to future crises and the subsequent economic recovery packages should, therefore, be more targeted. Specifically, they should consider the economic circumstances of women and other vulnerable groups in society.

[1] Vulnerable employment consists of self-employment and contributions to family work. Informal employment consists of economic activities with “the primary objective of providing employment and incomes to the persons involved” (GSS 2016).