How COVID-19 lockdowns and car-free days affected air pollution in Rwanda’s capital

Rising levels of vehicle traffic, industrial activity and urban sprawl are contributing to rising levels of air pollution across the global South. This is particularly the case in cities where urbanisation is progressing fastest.

In Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, the population has surged from less than 500,000 in 2000 to more than 1 million today. It is set to increase to nearly 2 million by 2030. At the same time, vehicle numbers in the city have increased from just 55,000 in 1999 to more than 200,000 in 2019.

Air pollution is the fourth highest risk factor for premature mortality worldwide. And there is growing recognition that even at relatively low levels air pollution can cause significant health impacts, such as heart attacks and strokes.

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) – such as dust, dirt, soot, or smoke – is 70 times smaller than a human hair and is one of the most significant contributors to urban air pollution. In Kigali, the amount of PM2.5 in the air is approximately double the level deemed permissible by the World Health Organisation. This emphasises the need for action and the scale of the potential benefit to be achieved. A challenge, however, lies in a lack of analysis on the sources of air pollution and the opportunities for action.

Using datasets on urban air pollution, we assessed the impact of car-free days – an innovative programme which encourages walking and cycling – and the COVID-19 lockdown in Kigali, Rwanda.

We found that PM2.5 was reduced by 15% on car-free days. We also found that the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020 – which reduced travel activity by over 80% – reduced air pollution by around 33%. A consequent partial lockdown, which allowed cars but not motorcycles, reduced travel activity by 41% and air pollution by around 21%.

Results from these analyses help us to understand both the causes of air pollution and the opportunities for policy action to address it.

Car-free Sundays

Started in 2016, on car-free days major roads are blocked off to provide space for collective exercise sessions to promote healthy living. Initially run once a month in 2018, the car-free days were made fortnightly and extended to secondary cities across Rwanda.

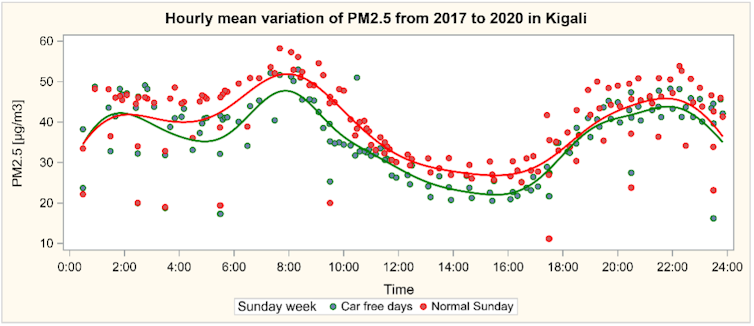

We found that, after controlling for the weather and seasonal

variability, car-free days reduced PM2.5 by about 15%. This led to a 3.7% reduction in total PM2.5 pollution in the city every year.

Air pollution on ‘normal’ and ‘car free’ Sundays by time of day.

The COVID lockdown

Lockdowns to prevent the spread of the new coronavirus also had a dramatic effect on traffic, creating an opportunity to explore its contribution to air quality. Using Google mobility data – estimates of travel activity developed by Google using mobile telephone data – travel activity was reduced by more than 80% during the full lockdown and by 41% during the partial lockdown.

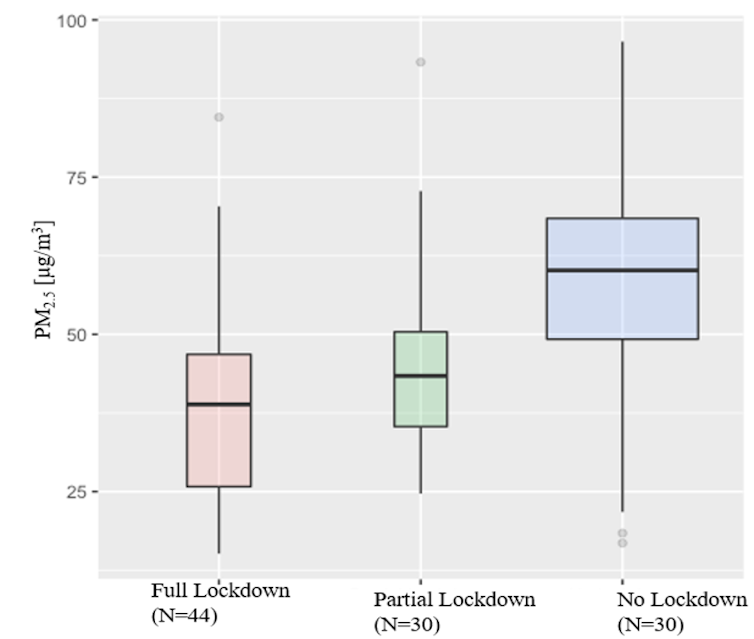

The full lockdown, which ran from March to May, required all traffic (excluding emergency vehicles) to stay off the streets. This reduced air pollution by around 33%. The consequent partial lockdown, which allowed cars but not motorcycles, reduced air pollution by around 21%.

These results emphasise the high significance of the transport sector in Kigali’s air pollution levels and the need for further action to address air pollution from the sector. In addition, with motorcycles remaining off the streets during the partial lockdown, the increase in air pollution during this period suggests that heavy vehicles and private cars, rather than motorcycles, are the main source of urban transport air pollution.

Levels of air pollution under the full and partial lockdown compared with the period following.

Next steps for policymakers

If the 20th century was the century of the car, an optimist might view the 21st as the century of multi-modal transport. Madrid, Vienna, Helsinki, Hamburg and Oslo have announced plans to become “car-free”. London, New York, Stockholm, Oslo, Singapore, and São Paulo are implementing charges on private cars that want to access certain areas of the city. And “bicycle mayors” (government officials dedicated to supporting the development of cycling) have been designated in Nairobi, Gaborone, Kampala and Cape Town.

This shift is in part a reflection of a growing awareness that air pollution is an economic growth issue and comes with substantial social, economic and environmental costs.

The analysis above and wider literature help to make the case for the comprehensive programmes of action in Kigali, and more widely.

Rwanda is one of only a few countries in Africa to have taken some positive steps towards managing air pollution. Since 2016, the Rwanda Environmental Management Authority has been authorised to carry out long term air quality monitoring. The authority also disseminates information to the public. In addition, Kigali has car zones to reduce traffic in the city and investments have been made into electric vehicles.

But more can be done. Extending car-free days across the week is not currently possible, but policymakers can support the expansion of public transport, invest in sidewalks and bike lanes, and work with the firms looking to implement shared cycling networks.

The disruptive lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 have provided policymakers with evidence to bolster efforts around car pollution. These include the enhanced testing and enforcement of vehicle standards, the implementation of bans on idling of cars (leaving cars running while stopped), and support for the growing number of firms around shared e-mobility.

![]()

This blog explores findings from this IGC project on the economic case for improving air quality in Rwanda.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.