How to reduce waste in the textile industry?

Textiles are an integral part of daily lives and the global economy, but their production and consumption often leave a global footprint of waste and pollution behind. A circular economy for textile can eliminate waste in the industry, which is a core sector of economies in the developing countries.

Textile has played a key role in world trade and global development all the way from the ancient silk routes to British imperialism, and the defining stages of industrialisation across the world. Currently, more than 60% of the world’s clothing is manufactured in developing countries. Leading with China (13%), Asia is one of the largest suppliers of textile, producing more than 32% of the world’s exports. With a total export value of over $400 million, East African countries like -Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda are also fast catching up in textile exports.

Production continuously moves to developing markets

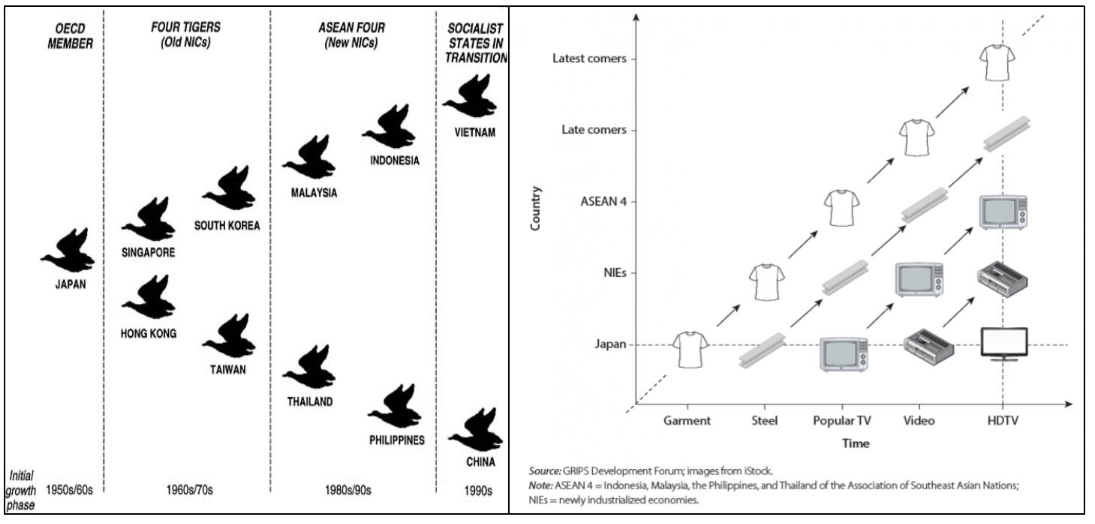

The 'flying geese model' of development popularised by Japanese economist Kaname Akamatsu in the 1960s contends that developing countries have historically succeeded by using apparel production as their first step towards industrialisation. The experience gained in light manufacturing – namely textile, clothing, leather and footwear – allowed countries to progress towards producing more sophisticated products like electronics and electric goods. Following this, the mass production of clothing that had started in western Europe during the industrial revolution (see Figure 1), had shifted to Japan by the 1950s, to Thailand and Malaysia in the 1980s and, to China in the 1990s. With each stage of industrialisation, the leading country or leader of the pack in the representative model, moved higher up in the value chain -producing more complex and durable products, while the others sequentially followed up (see Figure 2). Given textile’s past importance, it is likely that it may remain a steppingstone to further industrialisation for other developing countries in the future.

Figure 1 and 2: The ‘flying geese model' of technological and industrial development

Note: Figure 1 (left) depicts the pattern of the flying geese model of industrial development (source: The Sage Handbook for Urban Studies); Figure 2 (right) illustrates the sequential process of the model in manufacturing and trade (source: GRIPS Development Forum). *ASEAN 4 = Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines; **NIEs = newly industrialised economies.

Note: Figure 1 (left) depicts the pattern of the flying geese model of industrial development (source: The Sage Handbook for Urban Studies); Figure 2 (right) illustrates the sequential process of the model in manufacturing and trade (source: GRIPS Development Forum). *ASEAN 4 = Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines; **NIEs = newly industrialised economies.

From a linear model to a circular economy

Trends in the textile industry and its usage have changed considerably since the initial years of production. The MacArthur Foundation’s recent research suggests that while clothing production has doubled in the last 15 years, clothing usage has shrunk by more than a third – denoting the increasing growth of fast fashion and textile waste in some of the developed economies. Globally, an estimated 92 million tonnes of textile waste is created each year. By 2030, we are expected to discard more than 134 million tonnes of textiles a year worldwide. In addition, it takes a lot of water to produce cotton and other textile fabrics. It is estimated that 2,700 litres of fresh water are required to make a single t-shirt. That is enough water to meet an adult human’s recommended consumption for up 2.5 years. Textile dyeing is also known to be a major source of industrial water pollution. These environmental concerns along with the growing Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) compliance norms for major businesses in developed countries have brought the current “take-make-dispose” linear model of textile production under severe scrutiny.

Power and propagation

As a solution, many industry experts have suggested the circular economy model as the way forward. Taking its roots from industrial ecology, this model focuses on three major activities – reduction, reuse, and recycling. Following this, many global clothing brands have adopted sustainable systems in their day-to-day business practices. Similarly, multilateral initiatives like the UN Alliance for Sustainable Fashion, the Global Alliance on Circular Economy and Resource Efficiency to name a few, have been established to collectively respond to the wastage and pollution challenges of global textile supply chains.

The circular economy approach originated in the EU (a leading proponent of ESG compliance) and is currently primarily propagated by practitioners – businesses, business consultants, policymakers, NGOs and multilateral institutions. Rigorous academic or scientific literature on circular economies and its disproportionate effect on developing countries in terms of equity and climate justice is yet to emerge for broader understanding and dissemination.

How the circular economy can benefit developing countries

The current linear setup of the global textile industry takes raw natural resources (often from developing countries) transforms them into products (mostly used in developed countries) that are ultimately disposed off (primarily in developing countries). This sequence of events makes a circular economy model (that aims to close the gap between industrial production and natural ecosystem cycles) fundamental to climate justice and sustainability for the textile industries in developing countries.

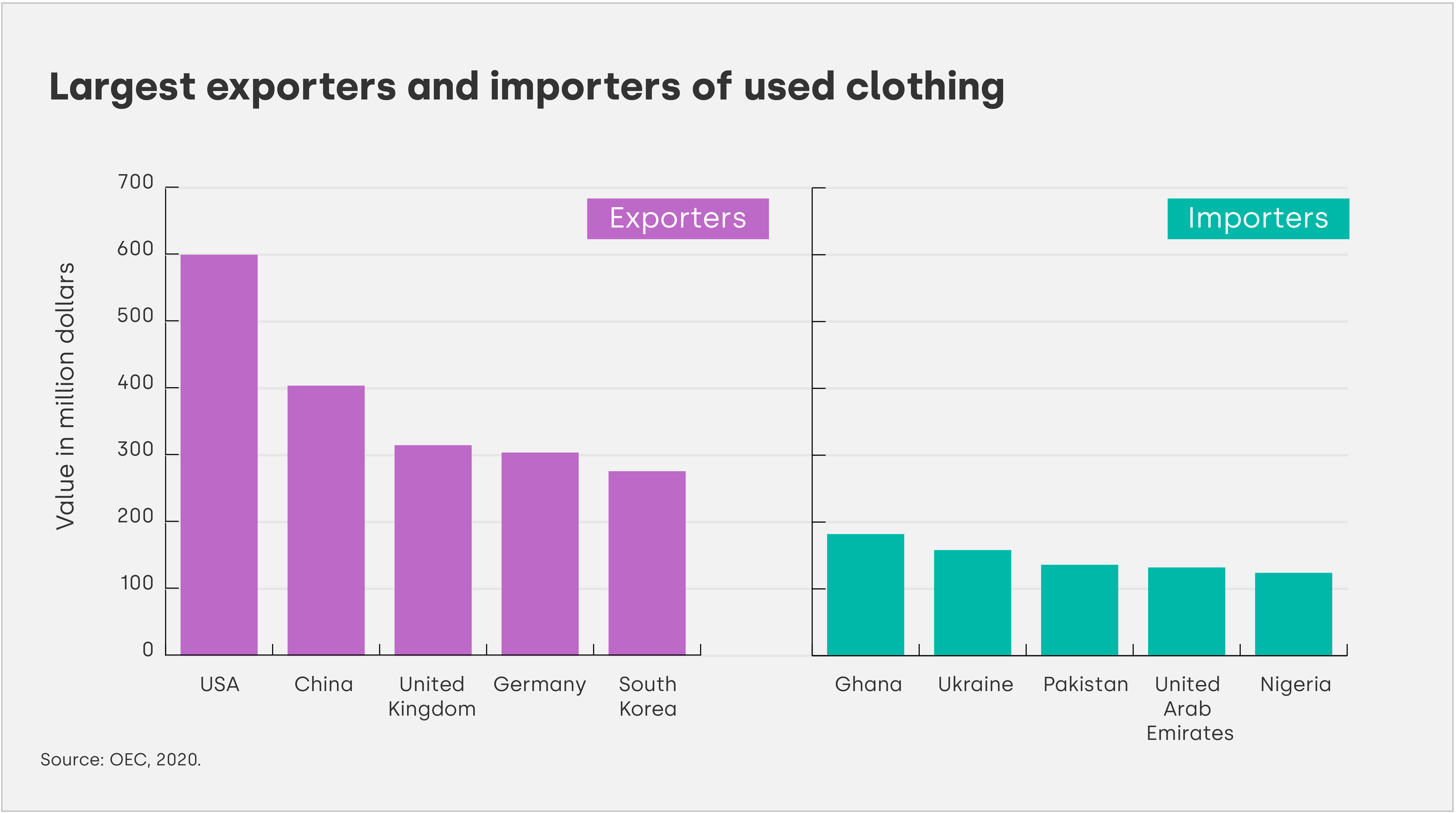

Figure 3: Leading exporters and importers of used clothing

Note: The graphs illustrate the largest importers and exporters of used clothing in the world market (source: OEC, 2020).

Note: The graphs illustrate the largest importers and exporters of used clothing in the world market (source: OEC, 2020).

1. Shifting the waste disposal burden: Globally just 12% of the material used for clothing is currently recycled. Data suggests that the US which is the largest textile importer is also the largest exporter of used clothing. Barring United Arab Emirates, the other importers of used clothing are developing countries like Ghana, Pakistan, and Nigeria. While developing countries are able to import cheap products from the US, this practice raises questions as to whether the burden of used clothing disposal is now indirectly passed on to developing countries through trade. Cheap imports of used clothing also raise questions on the impact of second-hand clothing on the growth of indigenous textile markets in importing countries and the knock-on effect on the local job market. Unless these questions are addressed in each country’s context by the requisite application of trade laws, the circular economic model may not be able to deliver sustainable development.

2. Technology transfer: The integration of developing economies into the circular economic model through technology transfer is fraught with complications around the sustainability and eco-friendliness of said technologies. Technology transfer can also help ameliorate the inherent problems that plague the textile industry – like pollution caused due to dyeing, excessive use of water, and irregular electricity supply. Dyeing of textile – one of the primary processes of textile production is known to be the second largest polluter of water globally. Textile dyes significantly compromise the quality of water bodies with toxins and carcinogenic elements. At the same time, many industries in developing countries suffer from loss of production from interrupted power supply. For technology transfer to be responsive to climate justice and wellbeing of the local population, technologies introducing cleaner production techniques or clean/renewable energy use should. However, this is often not the case as increased productivity and profitably are the main impetus behind technology transfers.

3. Promoting green investment: The financial sector can play an important role in mitigating some of the inherent in linear economic models by tying investment to the realisation of ESG requirements. However, compared to the EU and the US, a very small percentage of financial institutions in Asia and Africa currently include ESG consideration in their lending or investment decisions. In order to be a part of the green value chain, developing economies would need considerable amounts of green investments from FDI and commitments from FDI firms to observe the ESG requirements of their home countries even when they are not mandated in the destination countries.

4. Skills development: Along with green technology and green investments, there is a need for requisite capacity building and skills development in developing countries so that they can use, deploy, and maintain green technology in the global textile supply chain. Once again, this would require collective action support innovation and capacity building in the global textile industry.

Developing countries are often worst hit by the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation. While the circular economic model of production holds promises for the future, it raises many complex questions on the place of developing countries within it. There is a need to scientifically research and understand the components of the circular economic model in different contexts as well as understand the costs and benefits of its implementation.

Editor’s note: This article is part of our climate change series exploring the challenges and opportunities of promoting a low-carbon, sustainable future in developing countries.