How reforming energy systems can tackle climate risks: Evidence from Pakistan

Severe floods in Pakistan last year brought to fore the rapid, worsening effects of climate change confronting the country. At the LSE Environment Week, researchers and policymakers discussed the challenges facing Pakistan’s energy system and how it needs to be rebuilt for future climate risks.

Pakistan’s extreme flood events in 2022 affected over 33 million people and caused a 2.2% reduction in GDP. The severity of the damage caused will likely have consequential growth impacts, including limiting aggregate output and reducing worker productivity for years afterwards. Because of this impact, decisions on how to rebuild essential infrastructure–particularly in the energy sector–need to be made urgently.

Climate events damage fiscal resources and harm communities

Natural disasters are found to cause a loss in per capita GDP, and these recent floods will likely impede Pakistan’s return to its long-run, pre-flood growth trajectory. With tight resources, Pakistan has dispersed over US$ 264 million in aid to affected people, and has appealed for more funding from the United Nations to provide urgent medical care and food. The conversation on securing funding to rebuild infrastructure and invest in long-term assets has yet to begin, as immediate needs for providing medical care, shelter, and livestock are prioritised locally.

Severe time and budget constraints reduce the ability of policymakers to include transformative or innovative policies in the conversation surrounding effective policy solutions. In addition to this, Pakistan’s energy system is already saddled with pre-existing challenges to full implementation of reform. Some of the barriers are:

- scarce fiscal resources

- lack of saliency of policies with long-run climate benefits (in normal times)

- agriculture and transportation as the key drivers of emissions in Pakistan

In the policy process, reform has both winners and losers. Balancing the impacts in decision-making is both political and strategic. Energy system requires financing for improved and expanded infrastructure and increased renewable energy generation. Energy reform requires changes to the tariff structure by removing subsidies for fossil fuels and increasing transparency on payments to power suppliers to encourage more market participation. However, in a high-pressure fiscal environment, policymakers are struggling to make systemic changes.

The political and fiscal barriers Pakistan is facing have led to an energy deficit, where energy is not reaching the customers who need or want it. This is exacerbated by the flood impacts on the government’s resources and on Pakistan’s physical energy infrastructure. As a result, many Pakistanis are left with insufficient energy access – often the essential link in progress towards growth.

The energy system needs to be rebuilt for future climate risks

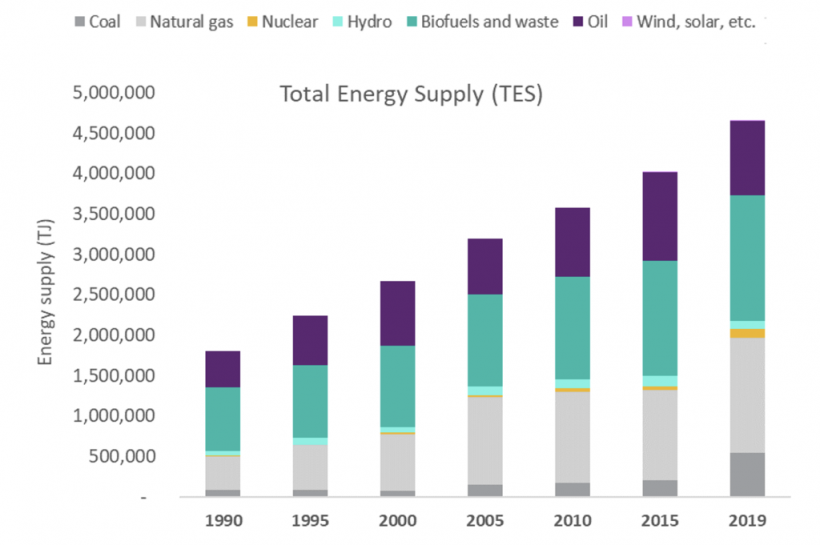

The energy system is essential to the health of the economic system. The 2022 flood events disrupted the primary river system which is responsible for 25% of the country’s energy supply. Currently, Pakistan’s grid is fuelled 63% by fossil fuels, 25% hydroelectric power and less than 6% renewable energy, as shown in Figure 1a.The current energy mix is not leveraging the estimated renewable or small-scale energy production potential.

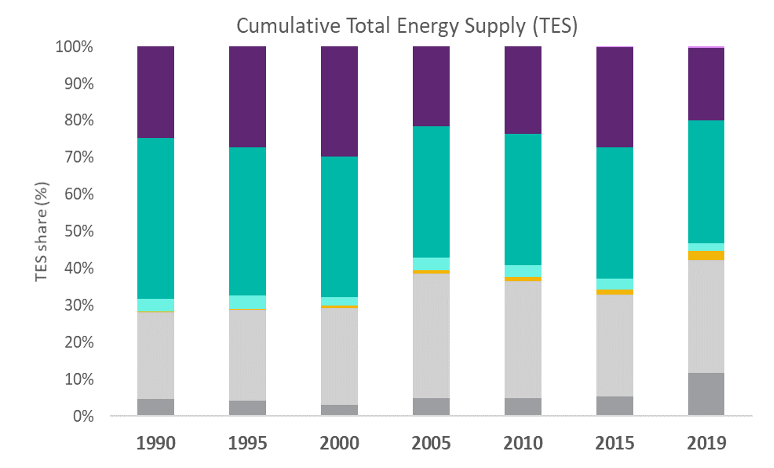

Figure 1a: Sources of Pakistan’s total energy supply (in terajoules)

Figure 1b: Cumulative shares of electricity generation by source (in percentage)

Note: Figures 1a and 1b shows the distribution of energy sources contributing to Pakistan’s energy supply. Most energy comes from natural gas, biofuels, oil, and coal.

Source: International Energy Association (IEA) 2021

The World Bank reports that 30% of energy should be renewables by 2030 in Pakistan. Recently, they approved a US$ 195 million financial agreement with Pakistan to improve electricity distribution and reform the energy market. This is a positive step towards providing Pakistan with the necessary resources to implement major renewable energy projects.

There has, however, been limited progress on developing the significant renewable energy potential of the country. Pakistan has trialled reliability-focused energy policies while also incentivising the low carbon energy sources that can provide less expensive and lower emissions energy. Net metering is available for projects < 1 MW. However, coal has grown as a share of the total energy supply (TES), and imports of natural gas from Iran and other neighbouring countries make Pakistan increasingly vulnerable to trade disruptions and price fluctuations. Pakistan is struggling to provide low cost, reliable energy services to its population– a service that is inseparable from economic development.

Increased renewable energy generation provides energy access quickly

With a few exceptional cases in the previous year, energy prices have fallen substantially. In Pakistan, the total energy supply (TES) per capita is increasing, but the per unit cost of energy to GDP is decreasing in Pakistan. More Pakistanis have access to energy and are using more on average, but the efficiency of firms’ use of energy is growing.

Pakistan now needs to identify a recovery pathway that leverages its availability of renewable energy while sustaining the growing levels of energy consumption that it has seen in the last decade.

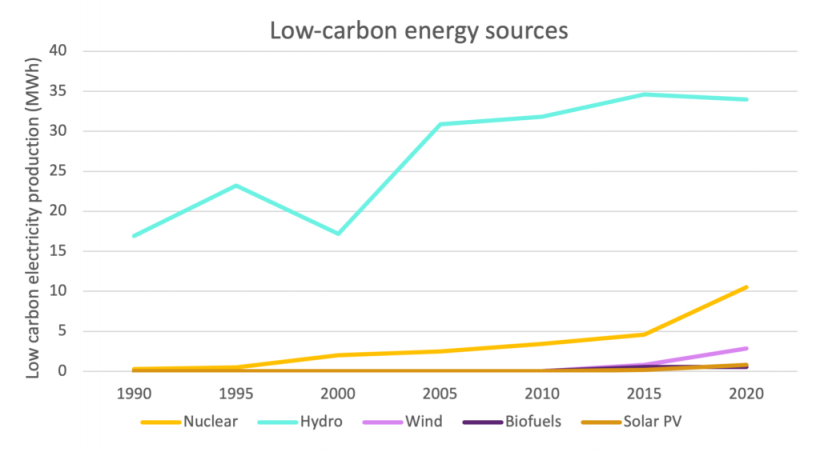

Figure 2: Low carbon energy production in Pakistan

Note: The figure shows the trends energy produced by low carbon sources in Pakistan between 1990-2020.

Source:IEA (2021)

Figure 2 demonstrates that solar and wind, although a very insignificant portion of overall low carbon energy sources, have seen an increase in installed capacity (GWh) by 260% and 280%, respectively. Even so, hydroelectric power is significantly higher despite the high year-round solar potential and the declining price. The difficult truth is that the energy system in Pakistan is suffering from low coordination, a lack of government capacity, and difficulty in regulating and pricing.

Expanding energy access requires a healthy market

Coal expansion has occurred due to variability in natural gas prices and new foreign investment in coal reserves. Pakistan has a government-managed energy system, and the price of energy must be kept low for consumers. Currently, asking customers to increase their marginal spending on climate goods is very unlikely, so the government continues to undertake investments to lower the cost of energy generation. Additionally, government subsidies are provided to compensate consumers for the difference in the standard tariff and production cost of electricity, selling below the optimal price in an effort to improve access. Unfortunately, this has led to an increase in fossil fuel based generation and creates an unsustainable and overburdened energy system.

Solutions are needed to expand energy access at a low cost, given Pakistan’s current fiscal environment. Energy reforms must also demand the integration of renewable energy, to ensure long-run, low-cost energy supply in a country teeming with potential for solar and wind. This includes:

- Taxation of air pollution: with significant political barriers to the creation of a tax, air pollution is salient, particularly in Pakistan’s cities. Taxing energy generators or industrial producers that produce associated air pollution could incentivise generators to invest in renewable sources of energy (without pollution). Industrial firms could demand low-carbon energy sources and adopt new technologies.

- Carbon tax for energy bidders: the imposition of the carbon tax for distributors at the bid-level in the market may ensure there is a pollution penalty while limiting the pass-through to consumers (all companies would have to bid at taxed prices). This could lead to generators bidding on more renewable energy sources that do not have the tax, and subsequently increase wholesale demand while generating more revenue from fossil fuel based generation.

- Improved privatisation and transparency of the energy market: this could create market incentives for producers and distributors to keep prices low. There is currently a culture of inefficient regulation and corruption that may lead to a private system with certain producers having unfair market control. Institutional reforms in tandem with the introduction of a private system could greatly improve the system.

Bridging policy and economics for decision-making

The changing nature of research in the fast-moving energy sector means that the level of importance of broadly applicable energy economics findings may not make it to policymakers in time. From the policymaker’s end, researchers are willing to work closely to overcome the specific financial constraints or other challenges which may be blocking energy reform. Some open questions still remain:

- How will the climate finance gap be filled? Much like other countries, and alongside the sentiments shared at COP27, Pakistan does not feel they are getting the promised share from developed countries.

- Loss and damage funding post-COP27 is available, but funding for revamping infrastructure and building out a sustainable energy grid is not as accessible. Will loss and damage funding include stipulation for shifting to a low-carbon system?

- Can Pakistan improve regulation and oversight of its energy market to encourage and incentivise renewable energy generation?

- How can energy system planning be conducted under deep uncertainty?

Editor’s note: To learn more about the climate priorities in developing countries discussed during the LSE Environment Week view the policy memos tabled and read IGC’s growth brief on sustainable growth for a changing climate.