How well represented are women in Pakistan's rural volunteer organisations?

Since the 1980s, Pakistan has followed a unique model of social mobilization that has contributed greatly towards rural development and poverty alleviation. This model of social mobilization and community participation involves setting up local community organizations at the neighborhood, village and union council (UC) levels.

These organizations comprise local volunteer citizens and are run like small firms with elected management bodies. Rather than address a single issue, they strive for overall community development and undertake activities in several sectors including health, education, microcredit, agriculture, infrastructure, disaster management, and conflict resolution.

The Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund (PPAF) is the apex institution managing this social mobilization process with support from local partner organizations (POs). A joint research team from the Lahore School of Economics, Oxford University, and Duke University is collaborating with PPAF to study these volunteer organizations and how they can be supported to better represent their communities and improve their activities. In the fall of 2014, the team conducted a baseline survey of 850 volunteer organizations formed at the UC level. These organizations are referred to as Local Support Organizations (LSOs) or Third Tier Organizations (TTOs). The survey gathered data through meetings with each organization’s executive body (EB) on their governance, activities, future plans and characteristics of the EB members.

Data on village characteristics and organization activity for every village were also collected from one local contact in every UC. In a randomly-selected subset of 150 UCs, a representative sample of households was interviewed to gather data on perceptions about these volunteer organizations and household-level assistance received from them. Based on this data, we found that women both benefit from and are actively involved in the governance and decision-making process of these organizations.

The main findings are as follows:

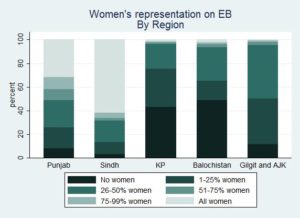

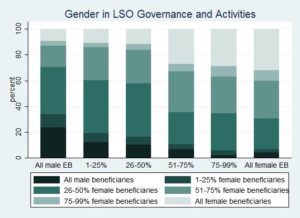

Women’s representation varies greatly. About 25 percent of the volunteer organizations have all-female EBs, while just under 20 percent of these organizations have all male EBs, with the rest having mixed-gender EBs. Gilgit-Baltistan and Kashmir have mixed-gender organizations with a significant women’s representation. Almost 90 percent have at least one woman on the EB, while half have at least 25 percent female EB representation (Figure 1). Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan – traditionally socially conservative provinces –have much less women’s representation, with more than 40 percent of organizations with no women on the EB. In Punjab and Sindh there are many volunteer organizations with only women on the EB, in part reflecting deliberate efforts by PPAF and POs in these provinces to organize women’s-only volunteer organizations in recent years.

Figure 1

Women are less active than men in governance. Women are less likely to attend EB meetings and speak less frequently when they do attend. In mixed-gender organizations, women are less represented in office than men, especially in leadership roles. At the lower management level (i.e. the general body), attendance is equally high for men and women. This likely reflects the lower commitment level required for participation in general body meetings, which occur much less frequently.

Women are more active in organizations where they form the majority. In organizations where women form the majority, the female EB members are much more likely to attend, and more likely to speak. More women in majority-female mixed volunteer organizations hold office. The greater participation of women in environments where they are more concentrated may simply reflect local culture: women in more progressive UCs are more likely to join the volunteer organization, and are also more vocal. It might also be the case that women EB members feel more confident expressing themselves and contesting office when there are more women in the group.

Women EB members come from similar or poorer households than their male counterparts. It is thought that for a woman to be represented, she must have some compensating advantage. This suggests women in volunteer organizations are mostly from wealthier households. But we do not find evidence for this. Women EB members are just as likely to live in mud-brick houses as male EB members, and in fact are more likely in Sindh and Balochistan.

Organizations with more women are less well known in the community. Based on the evidence from the household survey conducted in the UCs, organizations with the most women tend to be least well known in their communities – even among female respondents. This surprising finding might suggest that even women in leadership roles in rural Pakistan are less able than men to effectively promote their organizations’ work publicly.

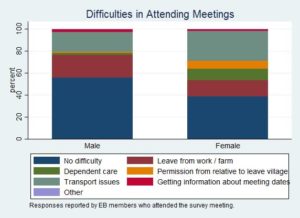

Practical constraints limit regular participation, especially for women. Significant numbers of both men and women EB members report difficulty attending due to work and transport issues, but more women report difficulties overall. Transport issues are the leading cause of difficulty for women, and are reported much more frequently than domestic responsibilities or issues with obtaining permission for leaving the village (Figure 2).

Figure 2

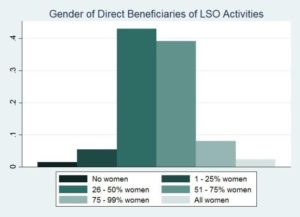

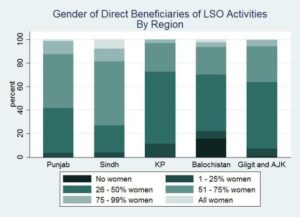

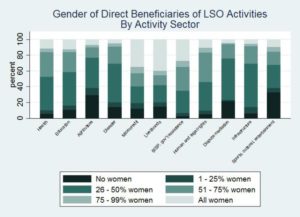

Local volunteer organizations tend to be more inclusive of women (and girls) as beneficiaries than in their governance. For almost 90 percent of volunteer organizations, women comprise at least 25 percent of their direct beneficiaries. Around 45 percent have a majority of women as their beneficiaries (Figure 3). The regional patterns of beneficiaries match gender representation in governance: the activities of organizations based in KP and Balochistan tend to directly benefit men more, while activities in Punjab and Sindh are more directed towards women (Figure 4). Microcredit and livelihoods programs are most heavily targeted at women, which in part is because of rules imposed by PPAF itself. Agriculture, dispute resolution and sporting/cultural activities more often target men.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Local volunteer organizations with more women in governance do more work targeted at women. Local volunteer organizations with more women on their EBs have more women as direct beneficiaries (Figure 5). Part of this occurs through project choice. EBs with more women’s involvement are also more active in health, education, microcredit, livelihoods, and human and legal rights. Those with only men’s involvement are more involved in infrastructure, sporting, cultural, and entertainment activities.

Figure 5

Figure 6

These findings provide a useful, detailed snapshot of the level of women’s inclusion in volunteer community organizations formed at the UC level across the country. However, these findings do not imply causal relationships that are important for policy making. For example, we know that organizations with more women on the EB serve more women beneficiaries, but we do not know whether encouraging EBs to include more women would necessarily increase the number of women beneficiaries.

An ongoing research project will help address these and other questions useful for engaging PPAF with TTOs. Through a randomized control trial, organizations in treatment groups are asked to submit regular reports on either active participation of women in EBs and general bodies, or on the women beneficiaries of their activities. Some volunteer organizations will be offered the opportunity to be publicly recognized if they improve the most in terms of women’s inclusion and other performance measures. The findings from this research will hopefully help guide PPAF practices in the future, build on the existing foundation of TTO organization and achievements, and better serve some of the poorest communities in Pakistan.

This blog was originally published on "Developing Pakistan - Where insights meet clarity on Pakistan's development".