Improving Tanzania’s power quality: Can data help?

For many Tanzanians, the sun sets and it’s pitch black – in fact, according to government data at least two-thirds of Tanzanians don’t have access to electricity. For those who do, many experience problems with reliability and quality of service – i.e. power cuts, and fluctuations in power supply that can damage equipment. This affects people’s daily lives and can be particularly damaging for businesses – from small village enterprises to larger manufacturing industries.

The World Bank Enterprise Survey showed that power outages in Tanzania cost businesses about 15% of annual sales. In contrast, a more reliable electricity supply often means higher income and more jobs.

The good news is that the gap in electricity access is closing through grid expansion by national provider Tanzania Electric Supply Company (TANESCO) and private ‘mini-grid’ service providers (such as Mwenga Hydro Power, Ensol, Power Corner, and Rafiki Power).

But reliability is still a big issue. Generating more electricity is important, but it’s not always the answer to the power problem. In Dar es Salaam for example, many reliability issues are caused by the distribution network – for example old cabling or unreliable transformers – rather than problems with the actual supply.

At the same time, customers increasingly want answers on why their energy needs are not being met. People on the streets in Dar es Salaam are asking whether the power supply is fair. Is it more reliable in affluent areas? Do business customers receive a better quality service than domestic households?

Can data provide the answers?

Granular data may shed some light. In Dar es Salaam, the Hivos/IIED Energy Change Lab is piloting the Electricity Supply and Monitoring Initiative (ESMI)to gather independent data on the quality of customer supply by placing monitoring devices strategically in homes and businesses across five city districts. This helps customers, electricity service providers and regulators understand where the blockages are.

After 8 months of data gathering across 25 locations in 5 districts across Dar es Salaam – namely Temeke, Ubungo, Kinondoni, Ilala and Kigamboni – we have found some interesting trends both on distinct usage and power outage patterns as well as identifying customer behaviour.

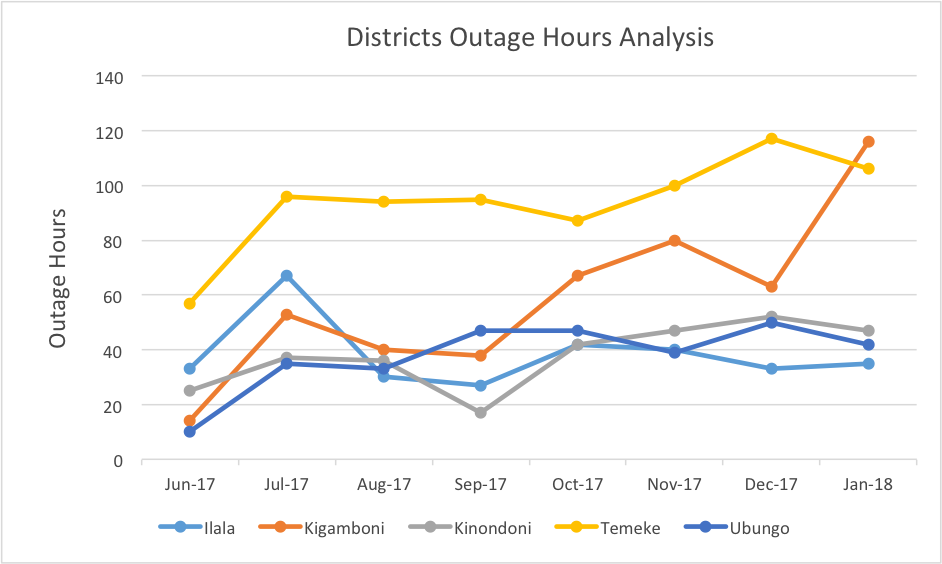

We measured ‘blackouts’ (Figure 1) as the total number of power outage hours per month.

[caption id="attachment_28185" align="alignnone" width="942"] Figure 1: Power outage hours per month across the 5 districts[/caption]

Figure 1: Power outage hours per month across the 5 districts[/caption]

In areas like Temeke, with comparatively high rates of power outages, widespread businesses such as hair salons, restaurants, and medical facilities are often forced to resort to other forms of fuel, such as diesel-powered generators. This has significantly increased the cost of operation that can potentially affect growth of businesses and discourage industrial activities in districts subject to power outages, such as Temeke.

In addition to Figure 1, which shows overall number of power outage hours per month, we measured percentage time where evenings had more than 6 hours power outage between 17:00 hours and 23:00 hours. Again, Temeke took the lead at 26%, with other districts as follows: Kinondoni at 25%; Ubungo at 22%; Illala 14%; Kigamboni at 12%.

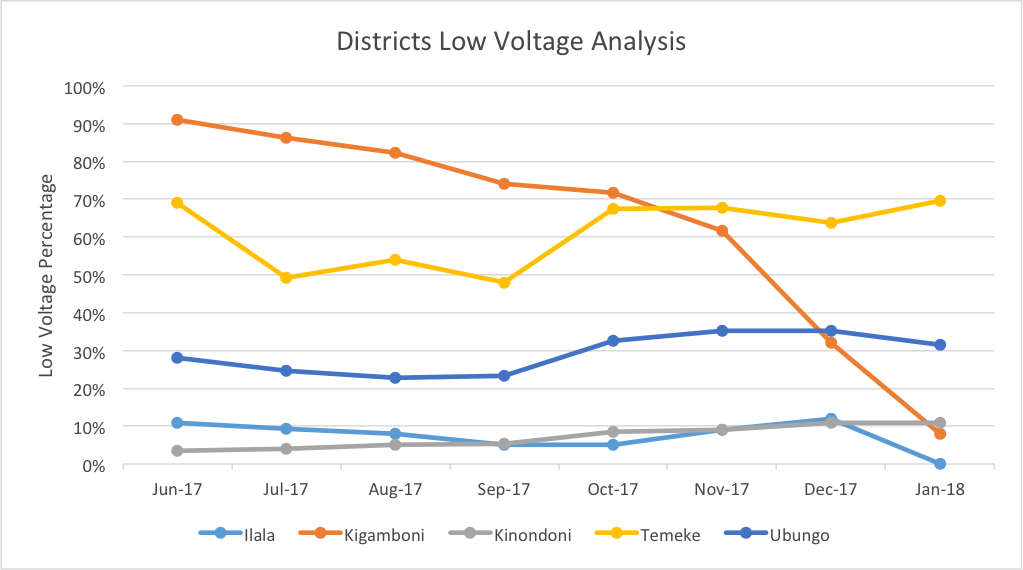

[caption id="attachment_28186" align="alignnone" width="1023"] Figure 2: Low voltage brownouts (% of power-on time with a brownout) across the 5 districts[/caption]

Figure 2: Low voltage brownouts (% of power-on time with a brownout) across the 5 districts[/caption]

When it comes to brownouts, Temeke was again the worst performing, with a brownout rate of 30%. Other districts performed as follows: Kinondoni 23%; Ubungo 23%; Kigamboni 13%; Ilala 11%. Data collected during this period shows a significant improvement in Kigamboni over time.

For businesses, revenue loss is due to more than just ‘downtime’ during blackouts: the combination of blackouts and brownouts can damage equipment and production-line restart costs for goods that are being produced are incurred during the power blackout or brownout.

More data, so what?

But how is ESMI data being used? Examining the pilot in Tanzania and in other locations including Indonesia and Kenya, we found the data is being picked-up in three ways.

- Raising awareness of the serious power problem. Availability of quality energy data helps to start a more informed discussion on improving customer perceptions of electricity service quality – prompting service providers to improve customer relations and perceptions about their services. Journalists whose beat includes power supply are making good use of the data for their stories. ESMI data has also been presented at multi-stakeholder energy sector workshops – for example in March in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania – as well as meetings convened by energy regulators. This has helped re-emphasise to regulators and others the value in monitoring power quality, particularly at the customer-level.

- Enhancing advocacy. The data strengthens customers and advocacy groups’ efforts to lobby power companies for losses and damage caused by poor power quality. For the first time, advocates have hard evidence of the availability, reliability, and quality of supply.

- Supporting research by decision-making institutions: regulators, parliamentarians, and power companies. In India some state level regulators are using the data to monitor utility performance. In Indonesia, staff from the national power company PLN have spot-checked power outages reported by their regional offices based on discrepancies the ESMI data identified. In Kenya, the ESMI pilot is being designed to support the World Bank’s efforts to assess availability, reliability, and quality of service to track progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 7 on energy access.

Next steps for Tanzania and beyond

A recent study in India by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) that looks at ESMI as well as other types of publicly available data, found little evidence of impact of the data on government accountability, effectiveness, and efficiency, in environmental stability or social inclusion.

We need a more deliberate process for using the data to influence change. For example, a strategy for greater public or political pressure, or strategically building capacity in individuals who can champion changes in how utilities and regulators function. These strategies will need to be sensitive to the political context.

That is not to undermine positive and progressive steps – India’s ESMI data is being used by multiple stakeholders and is forcing political debate about supply quality to be based on evidence, rather than just polemic arguments. But the biggest lesson so far is that achieving change is difficult, and takes time.

As part of the ongoing conversation the Energy Change Lab is having with the state utility, our aim is to actively involve TANESCO to aid in collection of more accurate data by working with them to have future ESMI devices installed at the transformer-level instead of having the devices at the household-level to enable the devices to cover a much wider area.

The Lab is also keen on engaging TANESCO to validate accuracy of the data we have collected in comparison to their own data to identify areas that might need immediate attention. We also hope this pilot and model of data collection will inspire other operators in off-grid areas to understand the challenges facing technologies they use, and potentially, it will help improve customer perceptions about their services.

Currently, we are in talks with TANESCO, exploring the possibility of conducting a much bigger ESMI pilot in Tanzania, we have also shared the ESMI reports with key energy actors and in March 2018, we convened a feedback workshop with key actors to cross-check our findings and suggest cross-sector recommendations.

Further, some issues are not inherently linked to better data or improving the way the service providers engage with customers. According to ODI, understanding why power outages happen in India calls for examining why distribution companies suffer losses (electrical and financial) and rely repeatedly on government bail-out packages. The report points out that – to keep costs down – distribution companies sometimes do not buy sufficient power from the power generation companies “which explains why many places in power-surplus India suffer so many power outages.”

National level processes like Better Power may provide a safe space to help identify and come up with solutions for some of these root causes.

Acknowledgements

The Electricity Supply Monitoring Initiative (ESMI) was pioneered by the Prayas Energy Group in India and championed in the global space by the World Resources Institute (WRI). The Tanzanian pilot of ESMI is led by the Energy Change Lab, a programme led by IIED and Hivos. Financial support for this Tanzanian pilot is provided by WRI, the International Growth Centre (IGC), and the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this post was first published by The Energy Change Lab.