The inflationary impact of the grain procurement policy in India

To smooth volatile grain prices, the Indian Government procures additional grain quantities, creating agricultural commodity buffers, often redistributed to poor households. This policy can produce a demand shock, triggering increased inflation. This blog looks at new IGC research to model the distortionary effects of such policies and potential monetary policy responses.

Introduction

Understanding monetary policy design in emerging markets is a growing area of research. One aspect missing in the literature is how distortions in the agriculture sector amplify the impact of a variety of shocks on output and inflation dynamics. In an ongoing International Growth Centre (IGC) project, a model was developed of the Indian economy to understand how a major distortion in the agricultural sector in the procurement of grain by the government affects inflation and output dynamics. The project provides a framework to understand these dynamics and in turn determine what the appropriate monetary policy response should be.

Grain procurement policy in India

Many developing countries, like India, have large agriculture sectors, which are inherently volatile. In India, the combined agriculture sector (agriculture, forestry and fishing) comprises 17% of gross domestic product (GDP). The employment share of the agriculture sector in India is also large: 47% (2013-14).

The Indian government periodically intervenes in the agricultural sector, especially in the food grain market, by directly procuring grain from farmers to create a buffer grain stock to smooth price volatility, and for redistribution to the poor. As part of the procurement policy, the government announces minimum support prices (MSP) before every cropping season for a variety of agricultural commodities. MSPs are the prices at which a farmer can sell the agricultural commodity to the government, and this is typically set above the market price. The procured commodities are then stored in Food Corporation of India (FCI) warehouses, from where parts of it are distributed to poor households. The rest of the produce remains in warehouses and serves as a buffer stock to offset future supply shocks.

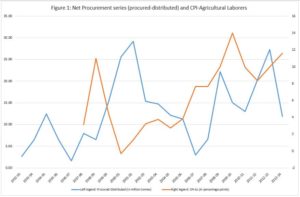

Net grain procurement per annum

The blue line in Figure 1, above shows the net grain procured (procured – distributed) of rice and wheat in millions of tons by the government of India. The average amount of net grain procured per-annum was approximately 13 million tons during the 1992 – 2014 period (8% of total production), while gross procurement averaged at 23.5% during the same period. The red line denotes inflation corresponding to the Consumer Price Index for Agricultural Laborers (CPI-AL).

As can be seen, in the last twenty-five years, net procurement trends upwards and has become increasingly volatile. CPI-AL measured inflation also trends upwards in the same period. Figure 1 suggests that by acting like a demand shock, procurement increases the open market price for grain because it creates a shortage in the open market. This leads to the question: are grain procurement shocks inflationary?

Figure 1 suggests that by acting like a demand shock, procurement increases the open market price for grain because it creates a shortage in the open market. This leads to the question: are grain procurement shocks inflationary?

The project: Terms of trade shocks and monetary policy in India

The IGC project, entitled “Terms of trade shocks and monetary policy in India” (see Ghate, Gupta, and Mallick; 2016), a three-sector (grain, vegetable, and manufacturing) closed economy model was developed of the Indian economy to understand how a major distortion in the Indian agriculture sector - the procurement of grain by the government - affects inflation and output dynamics.

The analysis is motivated by a host of other policy questions: should grain procurement shocks - by being potentially inflationary - affect monetary policy design? What is the inflationary impact of a procurement shock? What is the mechanism through which procurement shocks affect resource allocation in the Indian economy? It then calibrates the model to India to discuss the role of monetary policy in such a setup.

The main contribution is to use frontier level research to identify the mechanism through which procurement shocks – by leading to changes in the inter-sectoral terms of trade – get transmitted to the rest of the economy by leading to changes in aggregate inflation, sectoral output gaps, sectoral labour resource allocation, and the economy wide output gap.

Model description

A multi-sector model has the advantage of allowing one to understand the transmission of sectoral shocks across the economy. To this end, the model has both standard and non-standard features. There are four entities in the economy: a representative household, firms, a government, and a central bank. Households consume open market grain, vegetables, and manufactured goods. They also supply labour to all three sectors.

Labour is assumed to be perfectly mobile across sectors and the labour market is assumed to be frictionless. There is a manufacturing sector (M), which is characterized by staggered price setting and monopolistic competition, and an agricultural sector (A). The agricultural sector, which is also monopolistically competitive, is further disaggregated into a grain (G) and a vegetable (V) sector, which are both characterized by flexible prices. The reason for this disaggregation in the agriculture sector is to incorporate additional imperfections in the agricultural market that are specific to the Indian economy.

The model structure is most closely related to the seminal work by Gali & Monacelli (2005) and Aoki (2001). However, the paper features an explicit agriculture distortion – procurement – which is not a feature in these models.

The transmission mechanism: procurement, labour and inflation

The theoretical framework leads to new insights on the inflationary impact of procurement shocks, and the mechanism through which inflation gets generalized. When the government procures more grain, this increases the mark-up that grain producers charge over their marginal costs of production. This leads to higher prices in the open grain market, and inflation in the grain sector.

When the government procures more grain, this increases the mark-up that grain producers charge over their marginal costs of production. This leads to higher prices in the open grain market, and inflation in the grain sector

At the same time, the increase in the price of grain reduces the real marginal costs of production in the grain sector, inducing farmers to produce more grain, and hire more labour in the grain sector. The higher demand for labour in the grain sector pushes up nominal wages as labour gets pulled out of the other two sectors in the economy (vegetables and manufacturing), leading to an increase in nominal wages in these sectors as well. Confronting higher nominal wages, vegetable producers and manufacturing firms revise their prices upwards, leading to inflation in these sectors as well. This is how a procurement shock gets transmitted to the other sectors in the economy and leads to generalized inflation.

Confronting higher nominal wages, vegetable producers and manufacturing firms revise their prices upwards, leading to inflation in these sectors as well. This is how a procurement shock gets transmitted to the other sectors in the economy and leads to generalized inflation

Costs, prices and output

Because the costs of production (nominal wages) have risen in the vegetable and manufacturing sectors of the economy, procurement acts as a negative cost push shock in these sectors, reducing output. It is assumed however that the manufacturing sector is characterized by sticky prices: only a fraction of firms can revise their prices. Due to price stickiness in the manufacturing sector, actual output, falls by less than its natural level (the level of output if prices were completely flexible in the economy). This creates a positive output gap in the manufacturing sector on impact, as well as the economy wide output gap. Because the central bank responds to this increase in inflation and the positive output gap by an increase in the nominal interest rate, adjusted for the one period increase in expected inflation, the real interest rate rises. This dampens economic activity, and brings the economy back to the steady state over time.

A given output gap is now associated with higher inflation because of the distortion created by procurement. The response of the real economy to changes in the real interest rate decreases with higher values of steady-state procurement, thus requiring a stronger monetary response for a given output gap. The procurement distortion therefore affects the responsiveness of the economy to changes in the interest rate, which affects the monetary policy response.

The procurement distortion therefore affects the responsiveness of the economy to changes in the interest rate which affects the monetary policy response

Empirical evidence

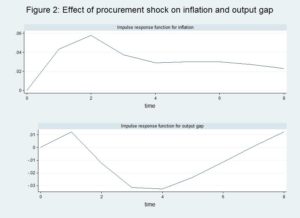

While the results are preliminary Figure 2, below, shows the response to procurement shocks on inflation (general-CPI), which is on the top, and the output gap, on the bottom. To run the model, quarterly data from 2004-Q2 to 2016-Q1 for these variables is used. As shown in the figure, on impact, the procurement shock increases inflation across all sectors. Although inflation starts falling after two quarters, it remains positive for about six to seven quarters after that. The effect of procurement on the output gap on impact is also positive.

Policy Contribution

Central banks in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) grapple with understanding the inflationary impact of procurement shocks because the precise link between the agriculture sector and the rest of the economy may not be well understood. In this project, a framework is developed to understand how the Indian government’s grain procurement policy in India can be inflationary, and determine what the appropriate monetary policy response should be. The analysis will be useful to both the Reserve Bank of India, and other EMDE central banks who want to understand how distortions in the agriculture sector amplify the impact of a variety of shocks on output and inflation dynamics in the economy.

References

Aoki, K (2001). ‘Optimal monetary policy responses to relative price changes’. Journal of Monetary Economics, 48 (1), 55-80.

Galí, J. & Monacelli, T (2005). ‘Monetary Policy and Exchange Rate Volatility in a Small Open Economy’. Review of Economic Studies, 72 (3), 707--734.

Ghate, C., Gupta, S. & Mallick, D (2016). Terms of Trade Shocks and Monetary Policy in India. Deakin University Economics Working Paper No. 7.