Insights from Nepal’s Abortion Legalisation

Are abortion and modern contraceptive methods substitutes? This blog explores the impact of the legalisation of abortion provision in Nepal.

The World Health Organization estimates that at least 13% of maternal deaths worldwide are linked to unsafe abortions. In trying to reduce those numbers, how much emphasis should policies place on making the procedure safer and more accessible within a well-regulated legal system, versus making contraceptives cheaper and more available? Addressing that question requires an understanding of the extent to which abortion and contraception are used interchangeably – namely, whether the use of one reduces the use of the other.

Background

In our recent paper Population Policy: Abortion and Modern Contraception are Substitutes we use Nepal's legalisation of abortion provision to study how the use of modern contraception (such as pills, condoms, sterilisation and injectables) changes in response to the availability of safe, affordable abortion centres.

Prior to the 2002 law that made the opening of these abortion centres possible, Nepalese women could be charged with infanticide and imprisoned for terminating their pregnancies. Under the new policy, senior gynaecologists from central and regional hospitals, as well as from some NGOs and private clinics, were trained to perform abortions and teach other doctors how to perform the procedure.

Registered abortion-providing health centres expanded rapidly in response, rising from zero to 141 by 2006, and to 291 in 2010. By 2010, the number of registered abortion providers per capita in Nepal was nearly twice that of the United States.

Notably, the new legislation only affected abortion; it did not affect the price or availability of contraceptives, make changes to other health services, or expand the health care workforce. An isolated change such as that observed in Nepal is atypical in heath policy, and affords researchers a rare opportunity to parse out causality.

one way to reduce expensive and potentially unsafe abortions may be to expand the supply of modern contraceptives

We use data on more than 32,000 women aged 15 to 49 from four waves of the Nepalese Demographic and Health Survey before and after the legalisation to obtain a detailed picture of fertility regulation practices and women’s fertility histories between 1996 and 2011. Combining these data with an official census of all legal abortion centres to track abortion availability, we are able to isolate how contraceptive use changes with abortion access.

Trends in contraception and legal abortion supply

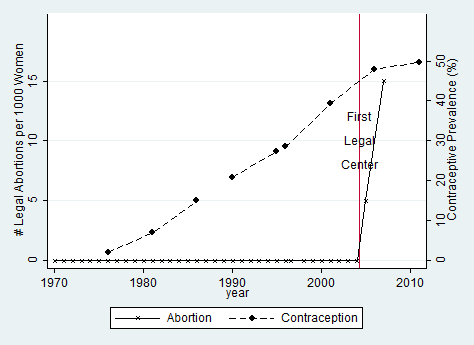

Let’s look first at the trends of contraceptive prevalence and abortion rates in Nepal over time. Figure 1 shows that there was a rapid and sustained increase in the use of modern contraceptives from the late 1970s until the mid-2000s (from only 2% to 48%). The break in trends appears to coincide with 2004, the year Nepal legalised abortion. From 2004, contraceptive prevalence plateaus. The rapid rise of abortion prevalence among women in Nepal appears to move in tandem with the plateauing of contraceptive usage. This co-movement is consistent with substitution.

Figure 1: Abortion and contraception trends in Nepal

Sources: Sedgh et al. (2011); Contraception: 1970-1987 from Mauldin and Segal (1988), 1990-1995 from United Nations (2004), and 1996-2011 from MOHP (2012).

Aggregate trends may, however, reflect changes in contraceptive use unrelated to the legalisation of abortion. Simply put, contractive prevalence may have plateaued for any number of reasons other than the change in abortion policy. A better test of whether or not the plateau is linked to legalisation of abortion would be to exploit district-level variations in the magnitude of abortion supply.

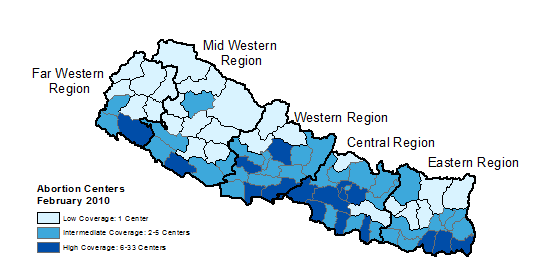

Figure 2 maps the concentration of legal abortion centres across Nepal’s districts. Splitting Nepal’s 75 districts into terciles (ordered thirds) illustrates that there is, in fact, substantial geographic variation in concentration across districts.

Figure 2: District-level Coverage of Abortion Centres

Source: Technical committee for implementation of comprehensive abortion care (2010).

Source: Technical committee for implementation of comprehensive abortion care (2010).

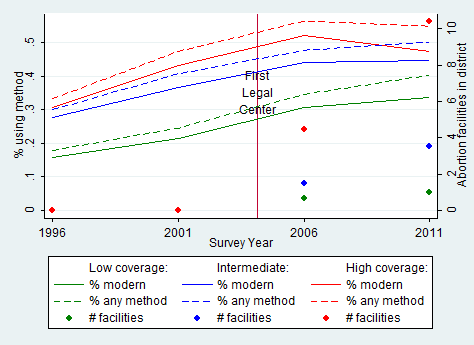

Using variation in abortion centre variations across districts, Figure 3 shows that the effect on plateauing of contraceptive prevalence is indeed greater in districts with higher concentrations of legal abortion centres. As access and availability of legal abortion increases in a district, contraceptive usage decreases.

Figure 3: Impact of district-level concentrations of abortion centres on contraceptive usage

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Demographic and Health Surveys of Nepal (1996-2011) (contraception) and Technical Committee for Implementation of Comprehensive Abortion Care (2010) (abortion facilities).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Demographic and Health Surveys of Nepal (1996-2011) (contraception) and Technical Committee for Implementation of Comprehensive Abortion Care (2010) (abortion facilities).

Methods

In order to implement a formal test of whether the opening of a legal abortion centre in a woman’s district indeed decreases the probability that she uses contraception, we use a ‘difference-in-difference’ approach. This approach controls for baseline differences in contraceptive use between districts and time trends common to all districts. This allows us to estimate the difference in the change over time in contraceptive use in districts where more legal abortion centres opened relative to the change over time in contraceptive use during the same time period in districts where fewer abortion centres opened.

An increase in the number of legal abortion centres in a given district is interpreted as a decrease in the full price of abortion (which includes direct and indirect monetary costs as well as psychological and physical health costs).

Findings

We do find evidence that abortion and modern contraception are substitutes for one another. Results indicate that when an abortion facility opened in a woman’s district, her odds of using contraception fell by nearly 3%.

On average, legalisation of abortion led to a fall in contraceptive use by 2 percentage points by those who are sexually active – compared to a baseline prevalence of 35%, and to an average annual increase of 2 percentage points before legalisation. Most of this decrease was among women who stopped using reversible methods of birth control, such as pills or injections. The effect on the use of more permanent contraception such as female sterilisations is less clear. The greatest shift in contraceptive use was by women aged 15-19 and 30-34.

Policy implications

This research shows that one way to reduce expensive and potentially unsafe abortions may be to expand the supply of modern contraceptives. That would mean making the full price of birth control cheaper (e.g., by reducing its monetary cost or making it more socially acceptable).

Conversely, policies that reduce the cost of abortions should also seek to reduce the cost of contraceptives if policymakers want to prevent abortion from being used as an alternative to birth control.

This relationship in family planning options also has important implications for foreign aid. The U.S.’s Mexico City Policy for example, prohibits international NGOs from receiving federal funding from the United States if they perform, advise, or endorse abortions. In related work on the Mexico City Policy, Grant Miller finds that the reduction in funding for family planning – as some international organisations elected to forgo U.S. support – reduced contraception access and inadvertently drove up abortion rates as women relied more heavily on abortion in the absence of contraception.