Line, tanker, tube well: Water and the politics of hybrid service delivery in Karachi

The distribution and sources of water in Karachi vary due to the numerous state and non-state actors involved. This has impacts on the burden on expenditure for water relative to income. It also affects blame-attribution and credit claiming for access to water, especially along the lines of ethnicity.

Water provision in Karachi is complex and layered. Individuals access water for domestic consumption through a hybrid system of private vendors, the illegal water mafia, and state-provided pipes. News reports regularly highlight the scarcity of water and the multifaceted politics—legal and illegal, state and non-state—around water provision. This makes both credit-claiming by party and state actors, as well as claims-making by citizenry, difficult.

In a new study including data from an original city-wide survey and focus groups, we map the distribution of water across Karachi. We examine variation in who citizens hold responsible for water scarcity, given the hybrid nature of water provision in the city. We find that while higher income groups tend to have better access to state-provided water overall, this is not an entirely linear relationship. Some districts have greater infrastructure for line water. While overall trust in state institutions like the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board (KWSB) is low, respondents vary—partly along ethnic lines—in who they hold responsible for water problems in the city. This, in turn, affects who they turn to for their resolution.

Variation in sources and expenditure burden of water relative to income

Water tankers in Karachi have a reputation for servicing primarily the ‘elite’ of Karachi. We find that almost everyone buys water from private vendors. These vendors might be the large KWSB-licensed vehicles trawling the city or small Suzuki pickup trucks with a large tanker at the back. While 55% of our respondents said that their primary source of water for bathing and cleaning was line water, 25% said they rely on tube wells, and an additional 20% reported primarily using tanker water. These percentages varied somewhat by income but there does not appear to be a linear relationship between income and reliance on tanker water. Rather, as table 1 depicts, low-income households and high-income households both relied on tanker water more than did middle-income households.[1]

Table 1: Sources of water for bathing and cleaning |

|||

| Line water | Tanker | Tube Well | |

| Overall | 54.9% | 20.2% | 24.6% |

| Low-income | 50.8% | 24.1% | 24.6% |

| Middle-income | 55.8% | 19% | 25% |

| High-income | 55.6% | 23.5% | 20.3% |

Note: The table describes the proportion of water coming to households from three different sources: line water, tanker, and tube well. These proportions vary according to the income level of the household.

Across the city, Districts Central, East, and South had more access to line water overall. District West and Korangi have the least access to line water. These spatial differences suggest that life is very different for the urban middle-class and the urban poor depending on where in the city they live. A low-income household in District West is much more likely to spend more on buying private water than a low-income household in District East or Central, which has a higher chance of having access to line water. Across the city, wealthy households are likely to have either some access to line water or be able to afford private water for domestic use.

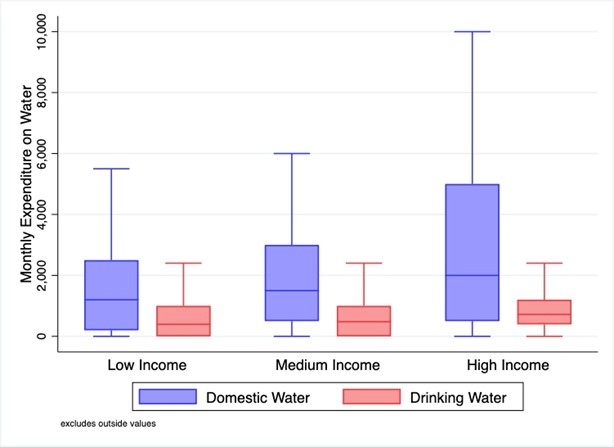

On average, people report spending about Rs. 2500 on domestic water, and an additional Rs. 736 on drinking water, every month. Figure 1 shows these values across three income categories: low, medium, and high. The average cost of monthly water expenditure per household varies significantly across income groups. However, the jump between low income and medium income is small. This suggests that wealthy families consume and pay more in absolute terms for water. It also suggests, however, that the relative burden of water expenditure is significantly higher for poorer individuals—a low-income family may spend up to 12% of their monthly income on water, whereas a middle-income family spends about 6%. Wealthiest families spend the least as a fraction of their income on water: just about 4%.

Figure 1: Water expenditure by income

Note: The figure shows the variation in water expenditure relative to income, i.e., the burden of water consumption for low-, middle-, and high-income households.

Credit-claiming and blame-attribution for water provision

Given the hybrid nature of water supply, who do citizens hold responsible for the scarcity of water provision? Field interviews conducted in summer 2021 highlight the multifaceted nature of political access to water and how this affects both credit-claiming and blame-attribution. During elections, for example, electoral candidates regularly make claims of improving access to water which would allow them to solve community water issues. During the 2021 by-election for NA-249—a constituency in the water-scarce Karachi West—newspapers reported that all the candidates “made water scarcity the core issue of their respective campaigns”.

Members of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) say that its links to the provincial government and oversight of KWSB give it access to state-provided line water. The Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) which has long retained control over Karachi city claims that its reach is at the local level—with activists and strongmen—and with mid-tier engineers (executive engineers, colloquially called XEN) which allows them access. For the MQM, many of these linkages are based on shared ethnicity. The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI), which won the 2018 national elections (including several key seats in Karachi), is also not above coercive pressure. A video from the Provincial Assembly proceedings in 2018 showed a PTI MNA from Karachi making an impassioned speech about water scarcity in his constituency. Yet, in 2021, multiple news reports suggested that the same politician “beat up” linesmen who were responding to complaints of water theft. In an interview with another senior politician from the PTI from 2019, it is evident that the party’s leadership in Karachi felt that they needed to “play dirty” in order to provide services to their constituency.[2]

Claiming credit for water provision while avoiding blame for the existing scarcity of water thus requires a careful balancing act. Opposition parties frequently accuse the incumbent PPP of profiting from bulk hydrants that service private tankers: according to one former National Assembly member, selling public water to tankers is “the easiest racket in town.” Meanwhile, the KWSB suffers from low levels of trust – their linemen are suspected of playing favorites and of being influenced by political power.

Variation in blame across ethnic lines

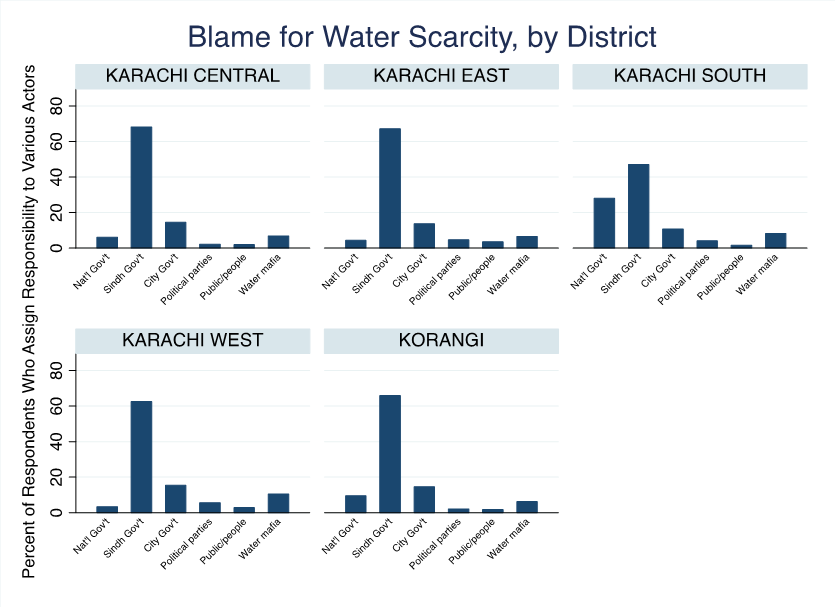

When asked who they held responsible for water scarcity in Karachi, the majority of respondents blamed the Sindh government. Sizeable percentages also held the city/municipal government, national government, and water mafia responsible. It is worth noting differences in blame-attribution across districts within Karachi, with Karachi South significantly more likely than other areas to hold the national government responsible, and Karachi West the water mafia (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Who respondents hold responsible for water scarcity, by district

Note: The figure shows the variation in blame attribution for water scarcity across different districts in Karachi.

Such variation exists along ethnic lines as well. Muhajir respondents were significantly more likely to hold the Sindh government responsible relative to other ethnic groups in the city. This finding is consistent with the fact that the PPP has dominated the Sindh government. Sindhi respondents, meanwhile, were much more likely to hold the national government responsible over other ethnic groups, and less likely to hold the Sindh government responsible. Finally, Punjabis were significantly more likely to hold political parties responsible.

Implications of variation in access to water

This study marks one of the first attempt to measure water consumption at the household level. It is crucial that a water ‘census’ be regularly performed by the city to assess how much access citizens have, particularly vulnerable groups such as women and low-income households. As with other bureaucracies, the Water and Sewage Board must be empowered to rationalise the distribution of water and collect payments for it. The massive shortfall in billing for state-provided water is a key contributor to its overuse, and the lack of incentives to curb unlicensed sale of this scarce resource.

Ensuring sustainable access to water across class and income groups in the city will require agreement on a basic level of water provision. The over-use and segmentation of water across rich and poor households is ripe for capture, as we see people blame entities such as the water mafia and the provincial government for siphoning off water. Disputes over water have already resulted in instances of inter-group violence. A major period of scarcity can lead to inter-ethnic violence and further exacerbate ethnic tensions.

[1] We categorise respondents as low-income if they report that their households receive Rs. 20,000 or less in income per month (n=557), middle-income are those between Rs. 20,000 and 50,000 per month (n = 710), while high-income are those with Rs. 50,000 or more per month (n=153).

[2] Haider interview with PTI MNA Ramzan Ganchi, February 2019.