Mobilising local leaders to rebuild the social compact

The social compact between citizen and state, whereby a citizen pays taxes and receives public goods and services, is a critical link in political accountability and the development process. This link is especially salient in the context of local governments and a significant metric on which they are judged. In many developing countries, however, this link is broken.

In many developing countries, citizens do not receive, or indeed even demand, high-quality services. This is, in part, because of limited local government spending resources given low levels of local tax revenue. Citizens, in turn, have low willingness to pay taxes due to a perceived, and at times real, disconnect between tax payments and services received, and a broader lack of trust in the State and the political process. On top of this, politicians may have low incentives to improve service delivery given various informational constraints limiting citizens’ ability to hold them accountable for service provision. This can create a vicious cycle where citizens do not receive high-quality services because resources are limited by low local tax revenue, and the low quality of services leads to a lower willingness to pay taxes, as well as a broader lack of trust in the State.

Breaking the cycle

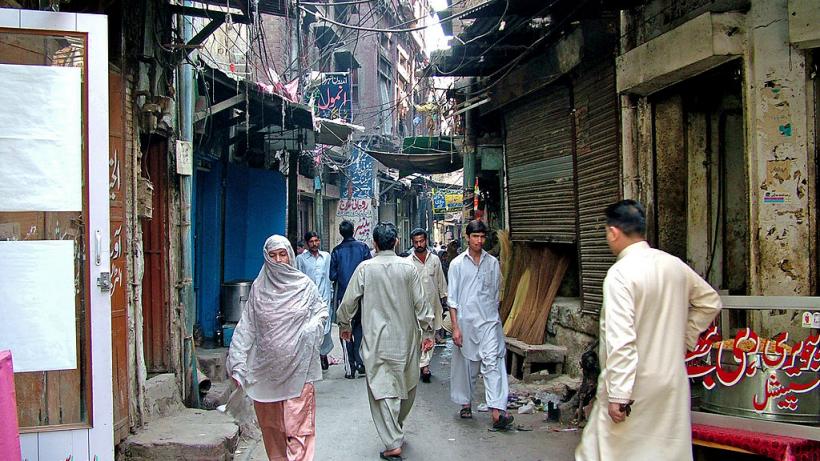

Our study seeks to examine how to break this cycle by mobilising local politicians to strengthen the link between the provision of local services and local property tax collection in urban Pakistan. With poor levels of urban service provision and tax collection and a weak social compact between citizens and state, Pakistan presents an excellent setting in which to address these challenges.

Our main focus is on whether mobilising local politicians on strengthening this link enhances:

- Input from citizens;

- Tax morale;

- Tax payments, and;

- Service provision.

We also go one step further and analyse the impact on political attitudes and the behaviour of citizens and local politicians.

To do this, we leverage an on-going randomised controlled trial taking place in neighbourhoods in Lahore and Faisalabad, in collaboration with the Government of Punjab, Pakistan, in which local governments are required to allocate tax revenue according to citizen preferences for local services. In Punjab currently, revenue is collected from administrative tax units and transferred to local governments that allocate these to city-level services. However, there is no linkage between taxes paid and services received at a lower and likely more salient geographical unit i.e. the neighbourhood (a contiguous set of typically 100-400 households).

Motivating local politicians

We motivate elected local politicians to encourage taxpayers in their constituencies to provide preferences for desired services when taxes are collected and encourage citizens to pay taxes so that these services are financed. In an effort to rebuild trust in the political process, the politicians take ownership of service delivery. They select the location of service expenditures within neighbourhoods and hold public events to inaugurate new services.

Specifically, each neighbourhood is assigned to one of three interventions described below:

- Local allocation. Local governments commit to allocating a portion of property tax collected from a neighbourhood to that same neighbourhood.

- Voice. Tax staff inform citizens of the tax-service linkage and give them a more direct voice in how their taxes are utilised by soliciting citizens’ preferences on which types of local goods and services should be prioritised in their neighbourhood. The results of this preference elicitation are shared with the local government in an effort to improve the allocation of

- Voice-based local allocation. This intervention combines the previous two. By both eliciting citizen preferences and requiring local governments to allocate a portion of property tax collected from a neighbourhood to that same neighbourhood, it seeks to make the tax-services link even more salient and credible. Citizens are informed of this earmarking, and the subsequent service expenditures are carried out in their

But how can we rebuild trust initially?

A key challenge in implementing these interventions, however, is credibly rebuilding trust in the system. To the extent that citizens do not trust the State, they may not even provide their desired preferences, let alone pay taxes in anticipation of better future service provision. Local politicians can play a critical role in building, or indeed hindering, the initial trust level required to give this process a chance. We, therefore, go one step further by including a local leader treatment. This involves assigning a local politician to coordinate taxpayer mobilisation efforts in his constituency.

Local politicians selected for this intervention are allowed to intervene at different stages, according to the following:

- In Voice and Voice-based local allocation neighbourhoods, local politicians introduce the intervention to taxpayers during town hall meetings;

- In Voice and Voice-based local allocation neighbourhoods, local politicians monitor tax staff as they collect taxpayer preferences;

- In Local allocation and Voice-based local allocation neighbourhoods, these politicians monitor and facilitate service delivery, using existing channels to pressure service providers and assist them in selecting service locations, and;

- In Local allocation and Voice-based local allocation neighbourhoods, local politicians hold public events to inaugurate new services and reinforce the link between taxes and

The mobilisation efforts aim to increase awareness of the interventions, encourage taxpayers to submit tax payments punctually and accurately, and remind taxpayers of the link (established by the scheme) between taxes paid and services delivered.

Progress report: Local leaders enthusiastic

We have completed the first round of interventions in all neighbourhoods and are in the process of implementing a second round. Our initial results suggest that:

- Local leaders were successfully trained about the link between taxes and services;

- Many local leaders were enthusiastic about the interventions being implemented in their constituencies, and;

- Some local leaders closely monitored and facilitated service delivery in Local allocation and Voice-based local allocation

Midway through the first round, however, the incumbent government of Punjab replaced the structure of local governments instituted under the Punjab Local Government Act 2013. A bill passed in the provincial assembly of Punjab (Punjab Local Government Bill 2019) proposed a new structure of local governments across the province and dismissed all locally elected officials. Until elections are held under the new system, bureaucratic administrators will conduct local affairs. We plan to train these administrators to continue implementation of the Local leader intervention.