The multiplier effect of Mozambique’s natural gas discovery and FDI bonanza

In the two years following the discovery, FDI inflows, driven by new projects in new industries, increased by 58%. There was also strong growth in manufacturing, retail, business services and construction, accompanied by substantial job creation.

Natural resources and growth

Natural resources are often thought of as a curse, slowing economic growth in resource-rich developing countries (Venables 2016). Yet a recent study by Arezki et al. (2017) pointed out that discoveries themselves may provide short-run economic booms, before windfalls start pouring in. This is because giant and unexpected oil and gas discoveries act as news shocks, driving the business cycle.

In new research (Toews and Vézina 2017) we show that giant oil and gas discoveries in developing countries trigger foreign direct investment (FDI) bonanzas in non-extraction sectors, in line with the insight of Arezki et al. (2017). Discovery countries, much like boomtowns during a gold rush, are inundated with injections of capital (Jacobsen and Parker 2014).

The study

Mozambique's offshore natural gas discoveries in the Rovuma basin since 2009 have been nothing short of prolific, with a discounted net value around 50 times its gross domestic product (GDP) (Arezki et al. 2017). While these fields are still under development as of October 2017, fDiMarkets data suggests that foreign firms moved in right after the first discovery in a multitude of industries, creating around 10,000 jobs in the following three years, across the country. In 2014 alone, it attracted $9 billion worth of FDI.

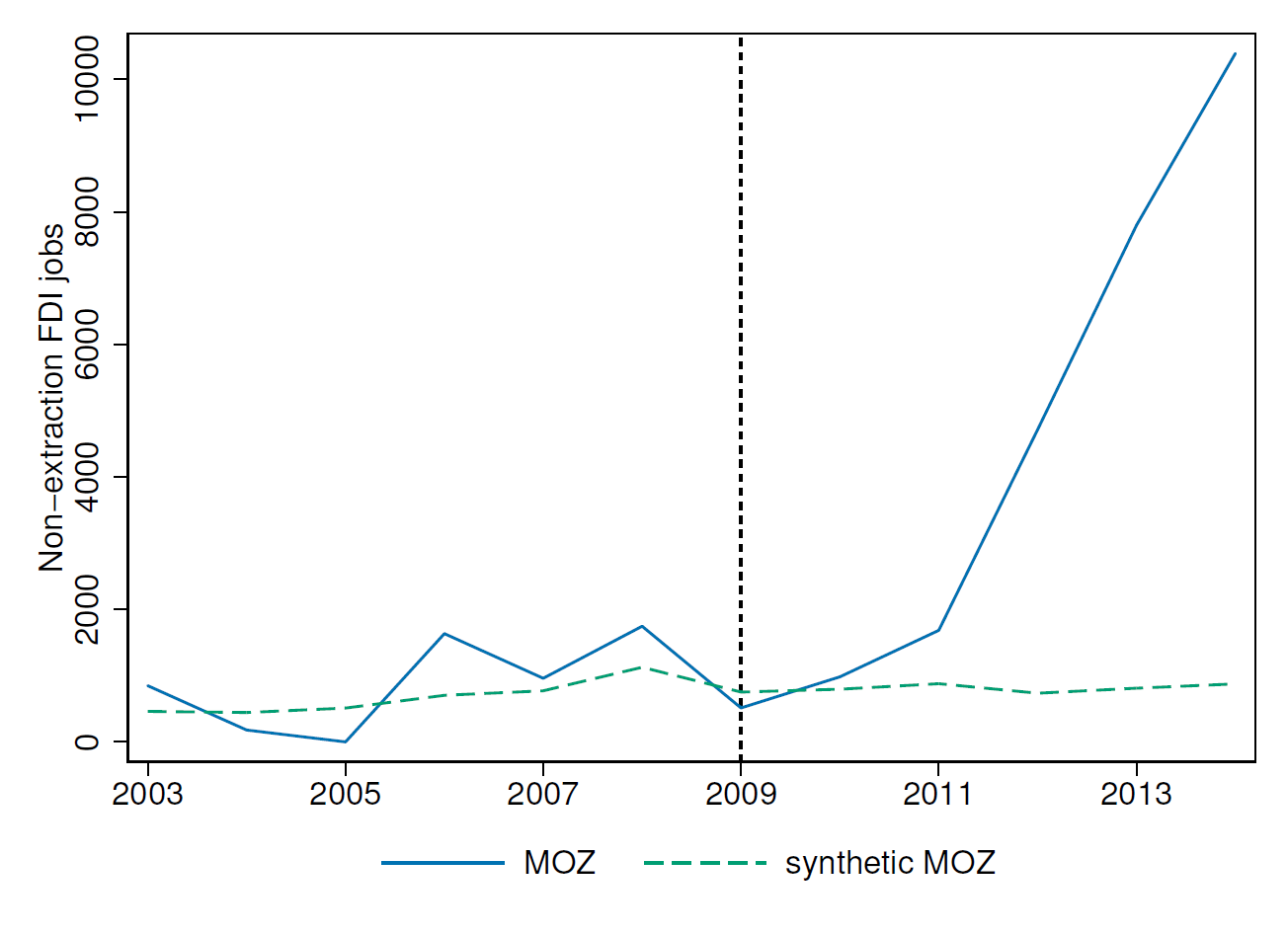

A counterfactual analysis suggests that none of this would have happened without the gas discovery. Indeed, the number of jobs created by non-extraction FDI in a synthetic control, a weighted average of FDI jobs in non-Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries with no discoveries that mimics Mozambique before 2010, remains flat around 1,500 jobs per year (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. The FDI effect of the Mozambique gas discovery

Note: The MOZ line is the estimated number of jobs created by FDI projects, as reported by fDiMarkets. Synthetic MOZ is a synthetic counterfactual, i.e. a weighted average of FDI jobs in non-OECD countries with no discoveries that mimic Mozambique until its first large discovery in 2009.

Findings: The local multiplier effect of FDI

To gauge the direct as well as indirect job-creation effect of the Mozambique FDI bonanza, we link FDI projects from the fDiMarkets database as well as data on firms from the 2002 and 2014 firm censuses (CEMPRE) to employment outcomes across districts, sectors, and periods, using data from two waves of Household Budget Surveys, also from 2002 to 2014. This allows us to estimate the FDI local multiplier.

- In this setting, we expect FDI jobs to have a multiplier effect due to two distinct channels. First, the newly created FDI jobs are likely to be associated with higher salaries (Javorcik 2015). In the context of Sub-Saharan Africa, Blanas et al. (2017) have shown that foreign-owned firms not only pay higher wages to non-production and managerial workers, but they also offer more secure (i.e. less-temporary) work.

- These newly created jobs are likely to increase local income, and in turn, demand for local goods and services. For example, the multinational employees might increase the demand for local agricultural goods such as fruit and vegetables, as well as for services such as housing, restaurants and bars. Such an increase in demand will be met by local firms by adjusting production, creating more jobs and reinforcing the initial increase in demand. Hence, the increased demand for local goods and services pushes the economy to a new equilibrium by multiplying the initial number of jobs directly created by multinationals (Hirschman, 1957; Moretti, 2010).

- Additionally, backward and forward linkages between multinationals and local firms might increase the demand for local goods and services (Javorcik 2004). Newly arrived multinationals might demand services such as catering, driving and cleaning services, as well as services from local law firms and consultancies that are more experienced with the economic and legal environment.

- Our baseline estimate suggests that for each new FDI job, an extra 6.2 are created in the same sector in the same district.

- Our results suggest that around 55% of the extra jobs created are informal rather than formal, around 65% are women jobs rather than men's, and that it is only workers with at least secondary education that benefit from the wave of job creation.

A thought experiment: Assessing the impact of FDI projects on job creation

On top of adding to our understanding of local multipliers (Moretti, 2010) these findings add to our understanding of the effects of FDI in developing countries (e.g. Atkin et al., 2015). To better grasp the magnitude of our multiplier we proceed with a thought experiment. If we removed all FDI projects from Mozambique in 2014, how many jobs would disappear? This includes all the jobs directly associated with FDI firms (131,486 jobs in 2014) but also all the non-FDI jobs due to the multiplier.

Findings:

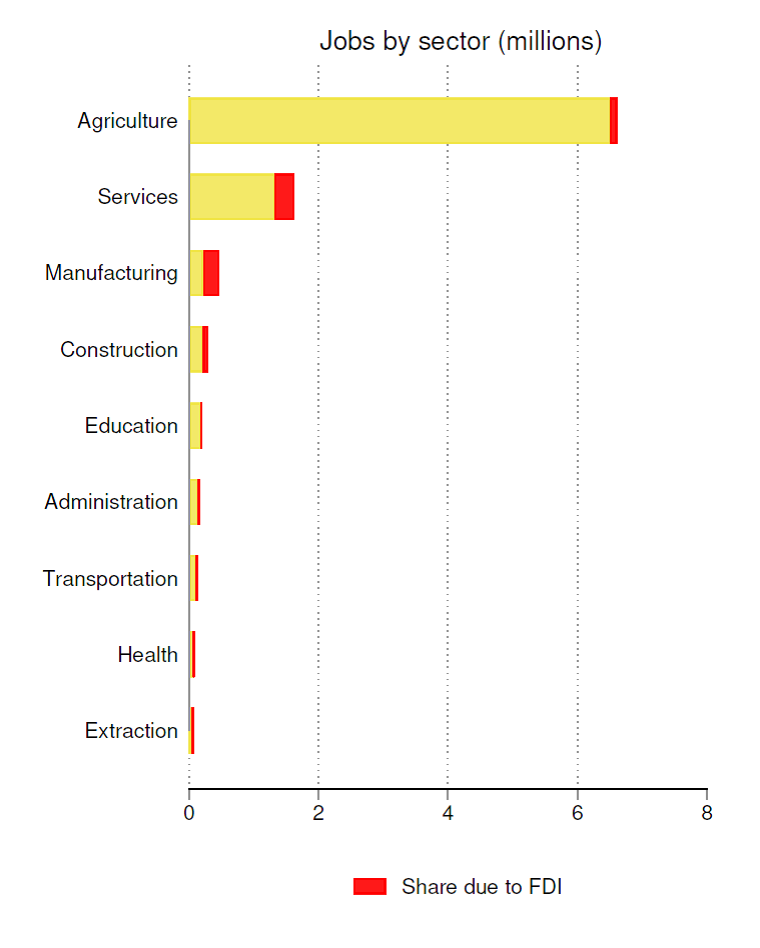

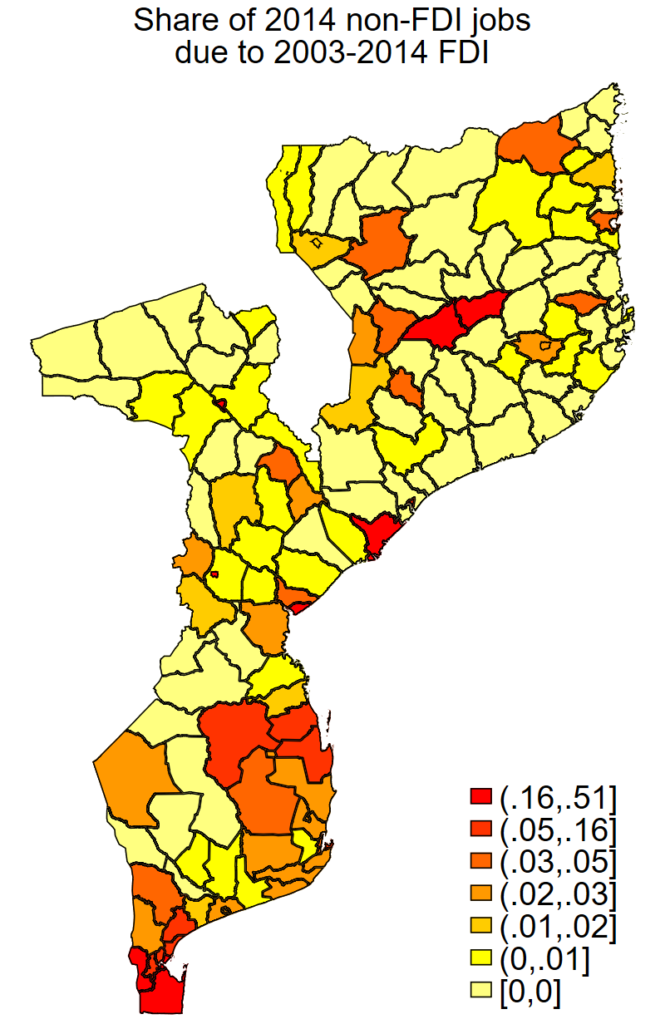

We simulate this drop and present the results by district and sector in Figure 2:

- There would be almost 1 million less jobs, out of around 9.5 million total jobs in Mozambique.

- The drop would be especially acute in manufacturing and in Maputo city, where more than half the jobs would disappear.

- In general, urban districts would see the largest drops.

- The number of jobs in services and even agriculture would also drop substantially, given the large number of people employed in these sectors.

In another back-of-the-envelope calculation, we can estimate the number of jobs that are due only to the FDI caused by the discovery:

- Based on the fDiMarkets job numbers and the counterfactual exercise in Figure 1, 21,500 jobs out of the 25,500 created by FDI in the five years following the first giant discovery in 2009 can be thought of as caused by the discovery.

- Hence, based on our multiplier estimate of 6.2, at least 133,300 extra jobs were caused by FDI projects that would not have happened if it were not for the discovery.

FIGURE 2. FDI projects and job creation in 2014

Note: The dark red part in the bar graph indicates the number of jobs due to FDI as per our multiplier estimate of 6.2. The heat map gives the share of non-FDI jobs due to the same FDI multiplier by district.

Conclusion

Our research suggests that FDI bonanzas triggered by giant natural resource discoveries can have large job-creation effects, notably via a multiplier effect. Giant oil and gas discoveries act as news shocks, creating expectations of future income and driving an influx of diversified investment, which in turn has the potential to provide an opportunity for a growth take-off.

Growth and diversification do not automatically follow from a large discovery. The Mozambique FDI bonanza occurred while the government accumulated an unsustainable level of debt and many of the FDI projects may only have short-run effects. According to O Pais, the FDI boom in Tete in northern Mozambique, went from Eldorado to nightmare when a coal project failed to materialise. Even so, FDI bonanzas do provide a growth opportunity and the FDI effect needs to be considered when analysing the effects of natural resources on economic development.

References

Atkin, D., Faber, B. and Gonzalez-Navarro, M. (2015), “Retail Globalization and Household Welfare: Evidence from Mexico”, Working Paper 21176, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Arezki, R., V. A. Ramey, and L. Sheng (2017): “News Shocks in Open Economies: Evidence from Giant Oil Discoveries,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Blanas, S., Seric, A. and Viegelahn, C. (2017). Jobs, FDI and Institutions in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Firm-Level Data, Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development Working Paper Series, WP 4 , United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. Accessible: https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/WP_4_0.pdf

Jacobsen, G. D. and Parker, D. P. (2014), “The economic aftermath of resource booms: evidence from boomtowns in the American West”, The Economic Journal.

Javorcik, B. S. (2004), “Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers Through Backward Linkages”, American Economic Review, 94, 605-627.

Javorcik, B. S. (2015), Does FDI Bring Good Jobs to Host Countries?, World Bank Research Observer, 30, 74-94.

Moretti, E. (2010), “Local Multipliers”, American Economic Review, 100, 373-377.

Rodrik, D. (2016), “Premature deindustrialization”, Journal of Economic Growth, 21, 1-33.

Toews, G. and Vézina, P-L. (2017), Resource discoveries and FDI bonanzas: An illustration from Mozambique, International Growth Centre, Working Paper. Accessible: https://www.economics.ox.ac.uk/materials/jm_papers/887/jmp.pdf