New era for aid: Is community driven development the answer?

If you missed the 2016 IGC Growth Week Conference, held at the London School of Economics, get caught up through our blog recaps looking at research highlights and policy insights. This post forms part of our blog recap series, looking at the challenges facing fragile states, and lessons from Afghanistan's experiences of rebuilding state capability. See here for other growth week recaps

Evidence on what does and doesn’t work in fragile states is unclear, and the impact of foreign aid, the most common solution propagated by international actors, on economic development has been heterogeneous. At its core, fragility is derived from state illegitimacy. This is reflected, symptomatically, in resource, institutional, and capacity deficits, all of which render states fragile and unable to deliver basic public services. Efforts to re-build institutional and resource capacities must first tackle the root causes of fragility and work to re-establish state legitimacy and reinforce state accountability to its citizens.

Traditionally, interventions in fragile states have attempted to rectify symptomatic resource deficits through foreign aid transfers targeted to gaps in capacity, revenues, and service provisioning. Not only has this proven ineffective but, in some cases, aid has further destabilised states.

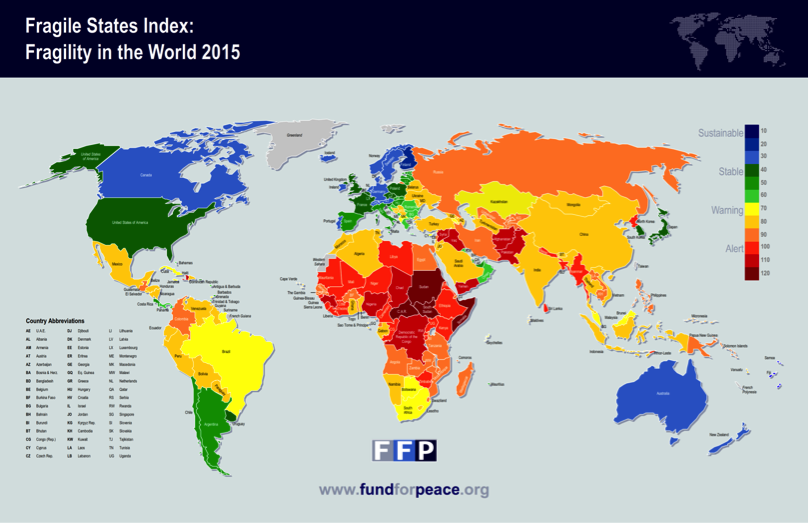

The IGC works in 14 countries, across Africa and Asia, nine of which are commonly classified as ‘fragile’, with an additional two that are neighbouring fragile states.

Source: Fundforpeace.org

As a framework for conceptualising future research needs on fragile states, Professor La Ferrara emphasised the central importance of citizen engagement for successful reforms and state rebuilding. Without engagement and citizen participation driving reforms, policy changes are unlikely to be sustainable.

Building upon this framework was a discussion by Mohammad Qayoumi, Chief Adviser to the President of Afghanistan which contextualised the framework in Afghanistan’s experience of reforms after the collapse of the Taliban regime.

In the case of Afghanistan, Dr. Qayoumi argued that foreign aid to Afghanistan has failed to acheive significant impacts due to a failure by donors to simultaneously build state capacity, and invest in human capital. Kabul, like all rapidly urbanising cities, faces a myriad of challenges, the biggest of which Dr. Qayoumi argued is its limited infrastructure. On the back of more targeted infrastructure investments, Afghanistan could rapidly expand access to energy, water, food, and housing for it's population. Transport and connectivity infrastructure has the potential to radically expand Afghanistan's opportunities for regional trade. For long-run growth, an effective Afghani state must overcome its pervasive security challenges and improve regional trading and connectivity for growth.

On fragility – New research and emerging ideas

The new wave of development research on fragile states has instead shifted towards initiatives that strive to increase state capacity through legitimacy. The challenge remains understanding re-engage citizens and re-establish trust in government. This means tempering social or ethnic divisions and eradicating inefficiencies and corruption endemic to fledging political and economic systems.

On-going research is categorised by one of four main approaches:

1. Participation

This most commonly manifests as Community Driven Development (CDD) - drawing heavily on direct citizen participation to ensure policies more strongly align with and represent citizen interests. Despite the potential for CDD to spur greater local development, CDD also runs the risk of elite capture. Programmes in Sierra Leone, Liberia and the DRC have tested CDD to varying degrees. Evidence from Sierra Leone suggests that CDD could be a model for local development and public goods delivery, albeit on a small-scale. Deeper changes to decision-making structures and social norms however, were not evident. Similarly, in Liberia and the DRC CDD appear to produce some gains to social cohesion and greater transparency around community spending, but larger shifts in power structures and community dynamics were again, absent.

2. Information provision

Access and availability of information on political performance of politicians is a defining feature of developed democracies. Barriers to information are prevalent in fragile states and reduce voters’ abilities to effectively screen politicians. Remedies typically provide either ‘ex-post’ information, such as scorecards, evaluating historical political performance or ‘ex-ante’ information, such as pre-election debates to evaluate candidate quality.

3. Transparent elections

Free and transparent elections remain the cornerstone of legitimate state authority. Emerging research has focused on voter education programmes, challenging social acceptance of vote-buying and on the impacts of new technologies such as mobile phones on detecting election fraud. Impacts of the latter have been mixed with some positive outcomes on voter turnout in Mozambique vs. and some negative outcomes related to election violence in Nigeria.

4. Legal or judicial reforms

Weak institutional capacity is a well-accepted feature of fragile states, but of particular importance to inclusive growth and poverty reduction is the quality of a state’s legal institutions. The poor in particular, are disproportionately disadvantaged in systems where they lack awareness of their rights or may struggle to afford formal counsel. Low security depresses economic activity by making doing business harder for firms, driving away potential foreign and local investors.

The bottom line is not that foreign aid flows should be halted, but instead that greater caution and consideration should be applied. New models of aid and engagements with fragile states must incorporate both transfers and capacity building initiatives. Additionally, new approaches by donors should work to ensure that fragile states are strengthened in a manner that is sustainable, even after aid transfers end.