“None of the above”: Protest voting, voter turnout and electoral outcomes in India

Indian voters can vote for “none of the above” in national and state elections. This option has raised voter turnout and provides insight into the behaviour of protest voters in elections that do not have an explicit protest option.

In 2013, the Indian Supreme Court set out to increase political participation with an unusual policy: it mandated the introduction of a “None of the above” (NOTA) option in all national and state elections. Votes cast as NOTA are counted and reported separately and have no impact on the results of elections. The winner is still the candidate who receives the highest number of votes.

The Supreme Court believed that NOTA would give voters more ways to express themselves at the polls, and that voters would respond by turning out in higher numbers, stating:

“Democracy is all about choice. This choice can be better expressed by giving the voters an opportunity to verbalize themselves unreservedly… [This policy] will accelerate the effective political participation….” (PUCL v Union of India, 2013, 44).

The study: Voter turnout and electoral outcomes

In our paper (Ujhelyi et al., 2018) we first ask whether the Supreme Court’s prediction that NOTA would increase turnout was correct. We focus on the elections of Indian state legislatures between 2006 and 2014. We use a variety of methods to estimate voter behaviour and ask how NOTA changed voter’s actions both in the aggregate and at the individual level.

Methodology

An important feature of our approach is that, for the electoral data, we do not rely on voter surveys but instead use only official administrative data from the Election Commission. To relate the constituency level returns to individual behaviour, we use an estimation framework from the Industrial Organization literature, where, by analogy, market level information is used to infer individual consumer choices.

Findings:

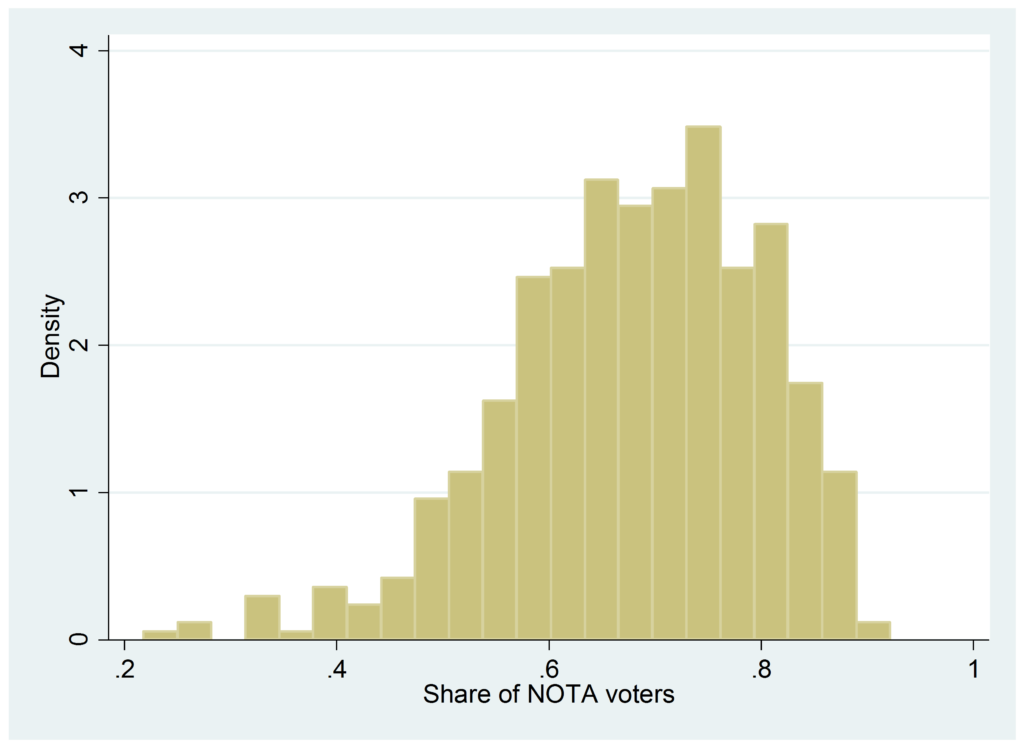

- Voter turnout: NOTA increased voter turnout by approximately 1-2% of the eligible voting population. This turns out to be close to the actual number of NOTA voters in the data. Indeed, we estimate that most voters choosing NOTA are new voters who showed up at the polls specifically to choose this option and would have abstained otherwise (Figure 1).

Clearly, many voters valued the option to express that they did not want to vote for any of the candidates listed on the voting machines. This appears to confirm the Supreme Court’s prediction that NOTA would increase voter turnout, by giving those who wanted to protest the option to do so within the electoral system.

Figure 1. Share of NOTA voters representing new voter turnout. The horizontal axis shows the estimated share of NOTA voters who would have abstained in the absence of NOTA (1 minus this share are the NOTA voters who would have turned out and voted for one of the candidates). The distribution is across 520 constituencies holding state legislative elections in 2013 in the states of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, and Rajasthan.

Figure 1. Share of NOTA voters representing new voter turnout. The horizontal axis shows the estimated share of NOTA voters who would have abstained in the absence of NOTA (1 minus this share are the NOTA voters who would have turned out and voted for one of the candidates). The distribution is across 520 constituencies holding state legislative elections in 2013 in the states of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, and Rajasthan.

Electoral outcome:

It is instructive to look more closely at the group of NOTA voters who would have turned out even in the absence of NOTA. These voters, making up about a third of NOTA voters, switched from one of the candidates to NOTA once this option became available. In principle, this could have affected the electoral outcome: in our sample, the vote share of NOTA was larger than the vote margin of the winner in about 8% of the constituencies.

Despite this, our findings indicate that the introduction of NOTA changed the electoral outcome in less than 0.5% of the constituencies. We estimate that, in the absence of NOTA, NOTA voters who still turned out scattered their votes across many candidates rather than coordinating on any one in particular. As a result, in most constituencies their choices had no impact on the election.

Protest parties

The findings beg two further questions:

- Which parties would NOTA voters choose in elections without a NOTA option?

We can identify several parties whose voters include relatively more protest voters (that is, voters who chose NOTA once it became available). These are typically small parties with radical platforms that never win a single constituency in our data.

- Do most of these parties’ voters choose them to express their protest against other candidates?

Our results indicate that most voters who choose these radical parties are not protest voters. Most of these voters appear to choose radical parties for other reasons than simply as a substitute for NOTA. In other words, while there are many protest voters, there do not appear to be any protest parties.

Many recent elections around the world saw an increase in the strength of non-mainstream, sometimes extremist candidates and parties. Some observers think that this is driven by voters protesting against traditional parties, rather than the inherent appeal of the radical platforms. At least in one setting our findings call into question such an interpretation.

References

Ujhelyi, G., Chatterjee, S. and Szabó, A. (2018). None Of The Above, working paper, University of Houston.