Preparing for urban floods in Mozambique: Can risk communication help?

Climate change has increased the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, and small- and medium-sized low-income cities are particularly vulnerable. In a recent project, I study if communicating risk can help prepare urban households for inevitable shocks affecting their livelihoods. Early results show that an easily scalable video intervention increased flood risk awareness and willingness to manage and mitigate flood risks in a Mozambican coastal city.

Information dissemination can be a powerful tool to guide, educate, and capacitate households in preparation for natural disasters. However, risk information and accurate forecasts do not always lead to their desired preparedness actions from communities at risk. Common reasons for the failure of risk communication include design and delivery flaws, lack of trust in authorities, and misunderstood risk perceptions. A post-disaster report on the 2019 Cyclones Idai and Kenneth in Mozambique concluded that even with accurate forecasts and warnings, many failed to fully comprehend the storms’ potential intensity and impacts. In addition, many lacked knowledge on how to take concrete actions.

Getting urban households to prepare for bad weather

In a new working paper, I use a randomised field experiment to evaluate a disaster awareness campaign addressing the challenges associated with risk communication. The setting is the Mozambican coastal city, Quelimane. This city is experiencing rapid urbanisation and is vulnerable to a variety of climate threats. During the wet season from December to April, Quelimane experiences floods from excessive rainfall and extreme winds.

For this experiment, I conducted in-person surveys with randomly sampled residents in the months preceding the 2021-2022 wet season. As part of the surveys, I showed videos about flood risk and how to prepare. The effect of the videos on risk perceptions and the intention to prepare is measured against a control group which watched a placebo video.

The content of the intervention videos was motivated by the idea that risk information is particularly effective if bundled with practical information on protecting against floods. I designed the videos to be easily understandable, by using non-technical language and visuals of flooding events and mitigating actions. Also, I guaranteed their inclusiveness by inviting both male and female speakers. Moreover, the videos were available in both the national language (Portuguese) and the local language (Chuabo). This turned out to be important, as 31% of the sample opted to watch the video in the local language. The two interventions covered the same information, but differed in the people speaking and featured in the videos:

- Public officials: One might expect that the inclusion of local government officials would increase the credibility and acceptance of the message. However, a potential lack of trust in institutions posed a threat. This intervention is relevant from a policy perspective because any large-scale information campaign will be associated with the official authorities.

- Flood victims: Featuring Quelimane residents with recent flooding experience may be more persuasive because of proximity to the viewer. The personal dimension of the message may make it more salient and trigger peer learning.

Risk perceptions and intentions to prepare increase after watching the public officials video

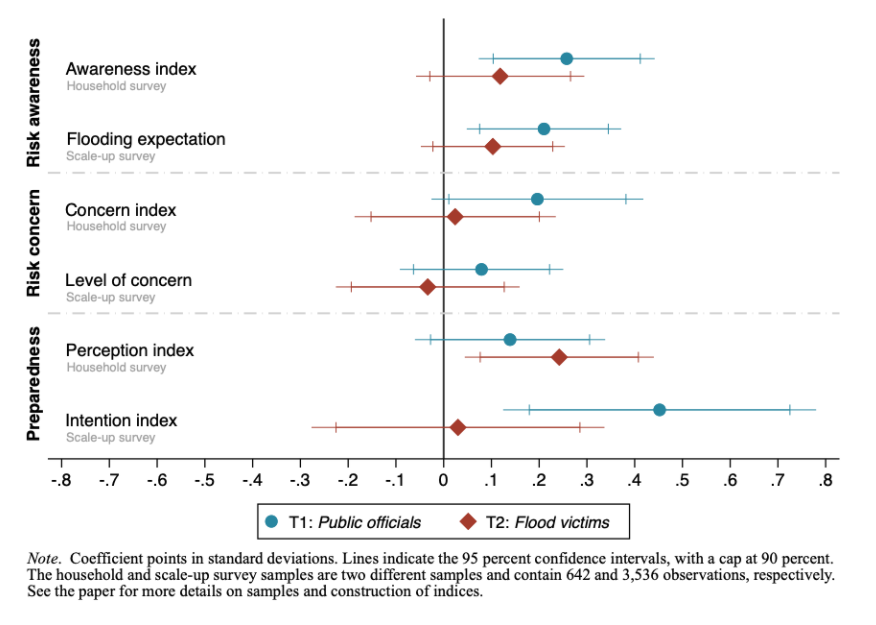

Figure 1 summarises the paper’s main results. After watching the public officials video, the respondents were more aware about the flood risks they faced. They also report a higher likelihood for implementing preparedness actions than respondents exposed to the flood victims and placebo videos. Taken together, these results suggest that it was not necessary to raise concerns or fear about flooding to increase the intention to prepare. The flood victims video did raise the perception that others would approve of taking preventive measures, thus influencing social norms regarding flood preparation.

Figure 1. Treatment effects on risk perceptions and preparedness intentions.

Recent flooding experience matters for awareness but not for preparedness

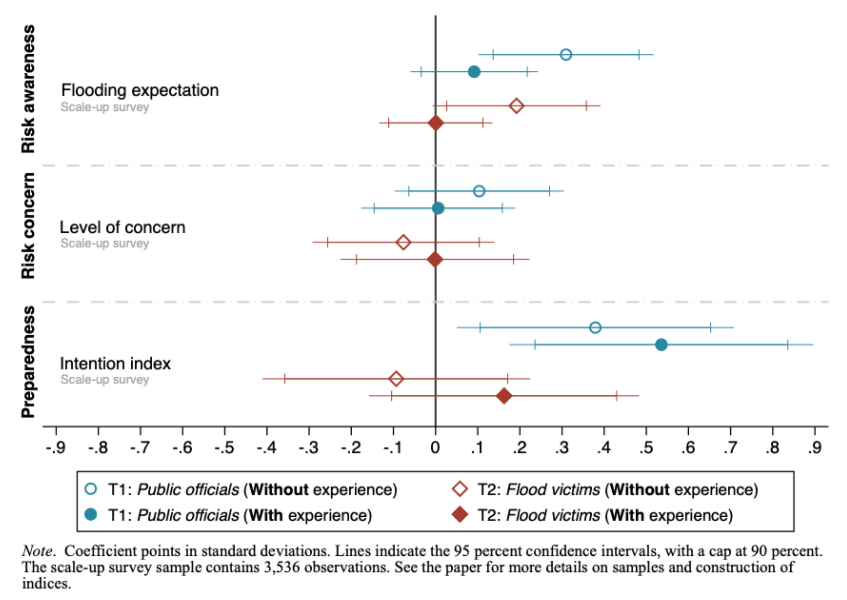

There is an emerging literature showing that past experiences raise risk awareness, risk aversion, and preparedness action. See, for example, studies about floods in Europe, cyclones in the Fiji Islands, and violence in Afghanistan. In line with these studies, households with recent flooding experience in Quelimane were already more aware and therefore their perceptions were not affected by the interventions. Figure 2 provides an illustration. In contrast, flood experience did not matter for the effect on the intention to prepare. This result highlights the importance of including examples of actionable mitigation measures in risk awareness campaigns because even experienced households might not yet be familiar with these measures.

Figure 2. Treatment effects depending on recent flood experience

Gender-responsive disaster risk management

A recent World Bank report shows that women and other vulnerable groups are more susceptible to disasters due to pre-existing inequalities and gender gaps. It is therefore crucial to systematically collect and evaluate gender-disaggregated data to promote and inform gender-responsive disaster risk management policies and interventions. In the paper, I show that the public officials intervention did not change the perceptions and intentions of men more than women. Moreover, scaling up the intervention through door-to-door visits or television would not penalise women in the studied context. Indeed, women were twice as likely to be home during the day and access to a television is balanced (around 73%).

Key insights for risk communication

Providing contextualised and easy to understand risk information to urban households before the wet season may present large benefits. Risk awareness can be improved even in a city where climate risk is extremely prevalent. Moreover, risk awareness campaigns should include examples of actionable mitigation measures. Households with recent flooding experience are more aware about risk but are not necessarily familiar with effective mitigation.

The results of this evaluation support both local and national policymakers in optimising disaster risk management strategies. Continued measurement during and after the 2021-2022 wet season will provide further insight on the persistence of these results.

Editors’ note: This article is based on this IGC project.