Prospectus of city growth: Rethinking planning in Amman

City administrations worldwide found themselves grappling with urban development issues that became more pressing during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Greater Amman Municipality conducted a retrospective assessment effort to better understand its early response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The IGC hosted a webinar examining the city’s self-assessment experience, which identified a suite of urban growth issues that are becoming more pressing by the day.

The COVID-19 pandemic has both highlighted and exacerbated the need to reassess urban planning approaches. The pandemic has brought to fore the shortcomings of the built environment and spurred a fresh reflection on urban planning at the city and neighbourhood levels. Cities like Amman, that struggle between aspirations of controlled urban development and realities of informal development, find themselves asking: what can be done to enhance the resilience of the physical built environment?

Exposing neighbourhood-level vulnerabilities in Amman’s built environment

Following the enactment of the National Defence Law in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Jordan entered a national lockdown. With austere restrictions imposed on people’s movement for a period surpassing two months, the lockdown was described as one of the strictest in the world. Jordan’s capital Amman—home to 40% of the country’s population, or four million residents, and 80% of its economic capital—was heavily impacted.

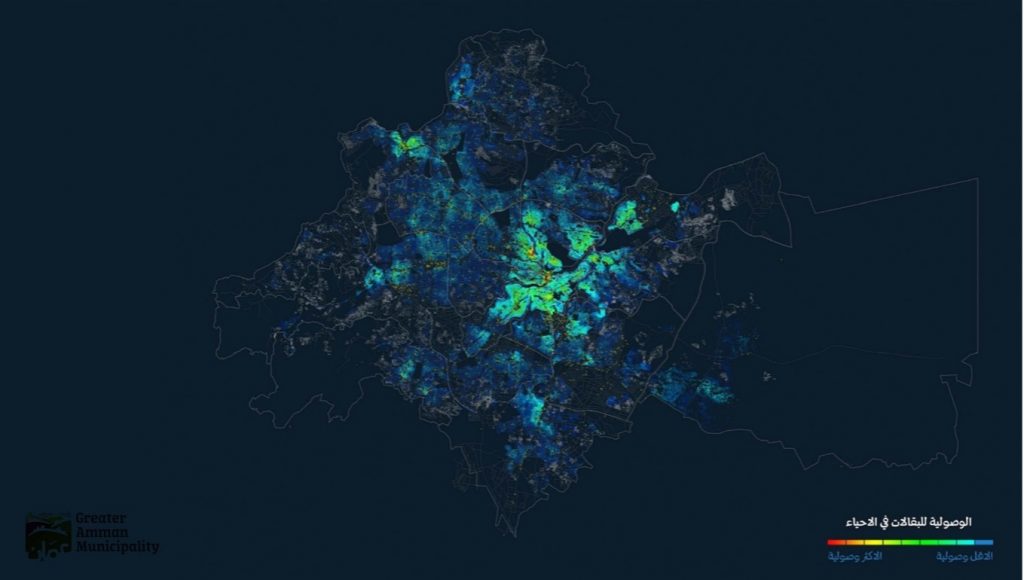

To better assess the city’s response to the pandemic and to identify neighbourhood-level vulnerabilities, the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM) prepared a report titled Amman City’s Institutional Performance and COVID-19 Resilience. The report, in part, analysed data on mobility, access to services, and air quality, where analytics revealed that most neighbourhoods have weak access to daily services such as groceries and healthcare. This became apparent when the lockdown restricted all non-motorised movement. The city’s design fuels low public space provision and weak access to local healthcare services, limiting the self-sufficiency of individual neighbourhoods and negatively affecting quality of life and resilience.

Figure 1: Accessibility to grocery stores in Amman’s neighborhoods. Spectrum of scale: Blue indicates low accessibility and red indicates high accessibility.

Source: Greater Amman Municipality

Rethinking planning in modern times

While exposing the lack of basic services at the neighbourhood level can trigger focused ideas for urban planning, city-wide land use presents its own dysfunctions. Healthy planning practices are key to ensuring reliable access to public facilities and land use compatibility.

Amman’s prevalent planning approaches and land use practices that affected accessibility during lockdown are, in part, the residue of years of successive initiatives.

One of the recommendations made in the city’s report calls for the preparation of a new master plan. However, despite the adoption of at least two master plans in the interim, the same urban challenges have persisted for more than forty years. This implies that a new master plan is not the ideal solution for said challenges. Rather, Amman’s urban challenges may be attributed to weak implementation of previous plans or perhaps even to the inappropriate actions proposed in them altogether.

Since the establishment of Transjordan in 1921, a series of planning initiatives have been initiated in Amman, with varied focus on land development and parcelling and signalling the city’s openness to planning. Though some planning exercises followed the 1955 master plan, the first comprehensive master plan prepared at the metropolitan level was not completed until 1988. Apart from spin-off projects, the plan was largely unimplementable. In 2008, the most recent master plan sought to depart from traditional planning by having a more strategic outlook. Still, its implementation remained limited and urban challenges attributed to the lack of proper implementation have persisted.

The development priorities and challenges expressed by the city planners today appear to be the same as those cited in the two master plans. The challenges include incompatible land use, poor walkability, shortage of public spaces, limited access to public facilities, and poor public transportation, among others. The persistence of these challenges suggests that planners in Amman should be asking key questions—Why are plans not implemented? What does this tell us about the planning process?—with promise to unravel significant issues.

The geopolitical context of the city certainly effects plan making and implementation. Still, planners have latitude within which they function outside the political environment. Amman’s master plans were informed significantly by the planners’ own ideological commitments, which are proving to be obsolete as COVID-19 continues to expose the built environment’s vulnerabilities.

Accordingly, and within this latitude, the planners now have an opportunity to depart from dominant practices and seek ways to make planning more effective and implementable. There is no quick fix that can prepare planners for this, but the process begins with the realisation that the current planning system, and the planning models it adopted over the years, did not function properly in the past, and are not fit for the current crisis.

Targeting density and crowding

Another shortcoming the pandemic highlighted is the speed of pathogen spread among crowded neighbourhoods. Planning for healthy neighbourhood densities thus becomes crucial.

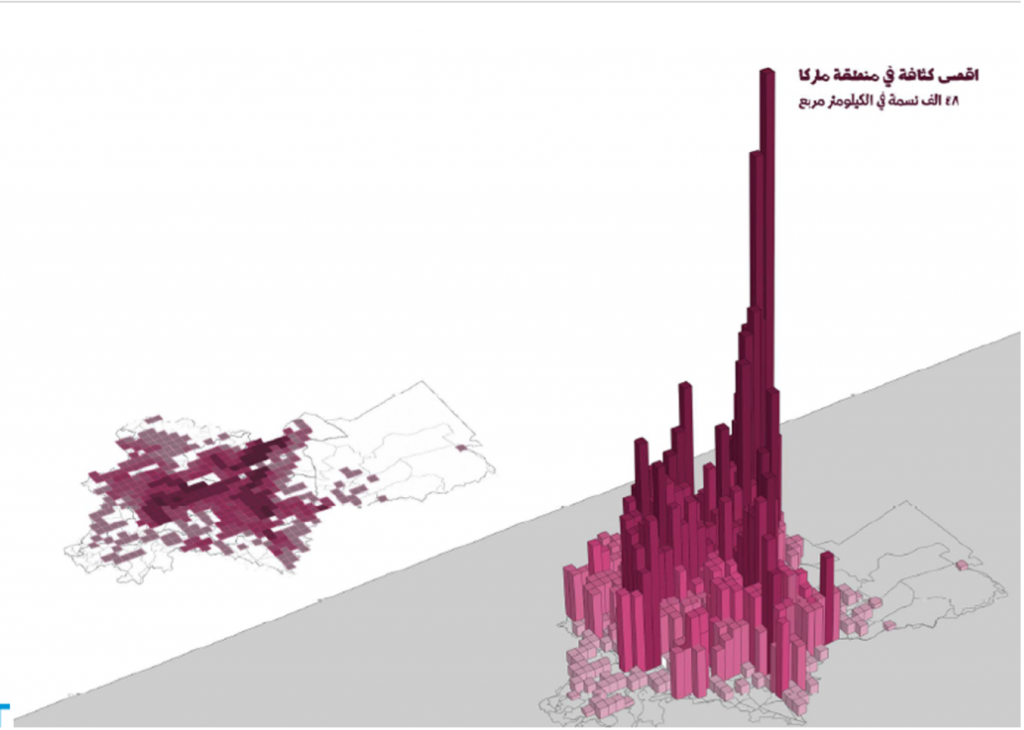

Traditionally, density has been viewed as a measurement tool of how many people occupy any given area of land. However, the pandemic has pointed us towards rethinking density by considering the type of density in place. Factored into this typification of density is the concept of crowding: the amount of internal space available to influence intensity of contact between a group of people over a certain area of land. Density does not necessarily reflect crowding. For example, Singapore and Mumbai have almost the same density, but people in Singapore have almost ten times as much built-up area per person. While Amman’s metropolitan density in 2017 averaged at 260 persons/km2, some of its neighbourhoods, like the Marka neighbourhood, surpassed 48,000 persons/km2.

City administrations should revisit densification plans by understanding crowding and land use across residential, commercial, and office zones and in public spaces.

Figure 2: (Left) Density map for Amman’s Neighborhoods (Right) Maximum density in Marka neighborhood at 48,000 persons/km2).

Source: Greater Amman Municipality

What can be done?

The general planning vulnerabilities exposed by the pandemic, combined with GAM’s useful diagnostic exercise, provides an opening for effective urban planning. A heavier reliance on localised analytics can help understand how well the current built environment functions by measuring the distance between plan aspirations and resident’s lived experiences. The mainstreaming and integration of these evidence-based analytics within GAM will be important for the day-to-day work as well as medium- and longer-term planning efforts. Importantly, revisiting the overall planning approach is critical for the city more broadly if it is to successfully implement post-pandemic planning initiatives.

Below is a list of suggested avenues for GAM’s consideration:

- Investigate the whole planning system to understand why planning has not worked and plans are not implemented, including:

- analysing what aspects of the master plans were materialised and what were not

- reconfiguring the practices that contribute to undermining master plan implementation

- re-examining land use distribution in vulnerable neighbourhoods

- investigating the reasons for success and failure

- Immediately put in place recovery plans that strategically focus on community planning as a substitute for comprehensive planning endeavours.

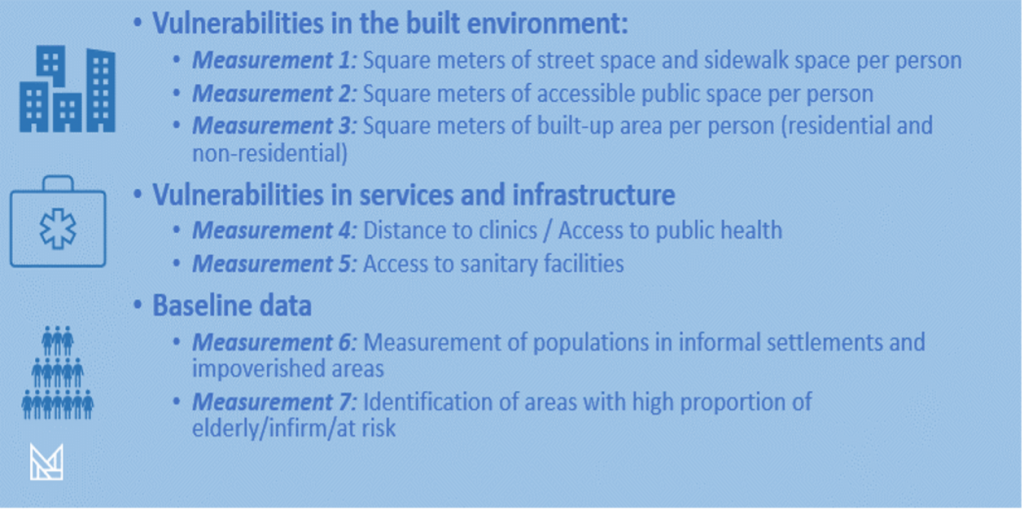

- Further deploy data analytics to understand vulnerabilities around density and crowding, including neighbourhood level measurements (Figure 3) that can be deployed to understand vulnerabilities and operationalise healthier levels.

Figure 3: Measurements for density and crowding

- Consider new approaches to public space design, with emphasis on resilience; this would require ensuring the healthy design and distribution of public spaces to strengthen accessibility in neighborhoods and provide for open-air leisure activities for well-being, cushioning lockdown effects.

- Increase public space provision. As public space provision has implications, including less corridors for cars, it will require effort to reduce the number of cars in the city and development a better transit system. Achieving this outcome promises to reduce crowding, increase efficiency, and enhance wellbeing by reducing the risk of infections and increasing freedom of movement.