A renewed South Africa?

Following an ultimatum from his own party, Jacob Zuma resigned as the President of South Africa on 14 February 2018. There is a sense of relief that the Zuma era is over, and optimism at the prospect of new leadership. However, cleaning out the deep corruption that’s taken root in South Africa will be no small feat. What lies ahead?

This past week has seen a notable shift in South Africa’s leadership, involving the resignation of president Jacob Zuma, and his replacement with Cyril Ramaphosa, a successful businessman, anti-Apartheid activist, and politician. Ramaphosa took over the African National Congress (ANC) presidency in December 2017 and is believed to have been Nelson Mandela’s favoured choice of successor.

Zuma’s resignation as president of South Africa, on the evening of 14 February 2018, ended an acrimonious few days during which the ANC’s national executive committee had attempted to recall Zuma. Zuma allegedly refused to step down, stating that he wanted a three-month notice period. He reluctantly capitulated after being informed that the ANC would table a vote of no confidence against him if he did not resign within 48 hours.

Although Zuma has faced, and survived, a number of votes of no confidence in the past, this would have been the first supported by his own party.

Corruption and no confidence

Zuma must have realised that the game was finally up. There was no way he could survive a vote of no confidence brought by the ANC. Additionally, hours before his resignation, heavily armed police raided the Gupta family’s luxury Saxonwold compound. The Gupta’s are close Zuma allies implicated in government corruption and state capture in South Africa. The home of Duduzane Zuma, Zuma’s son and close Gupta associate, was also reportedly raided. It was becoming clear that the winds were no longer blowing in Zuma’s favour.

It is thought that the raids on Duduzane Zuma’s home and the Gupta compound are connected to the Vrede Farm scam – a dairy project meant to provide assistance to indigent farmers, which instead defrauded the Free State provincial government of almost R150 million (some GBP 9.2 million). Following the raid, a number of Gupta associates have been arrested and charged with fraud and money laundering. Police are reportedly still on the hunt for Duduzane Zuma and at least one of the Gupta brothers.

Market implications

The financial markets have welcomed the news of Zuma’s exit. As news of the raids and Zuma’s resignation broke, the South African rand surged to 11.56 against the USD, the strongest it has been in three years (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: United States Dollar to South African Rand

Source: XE Currency Charts

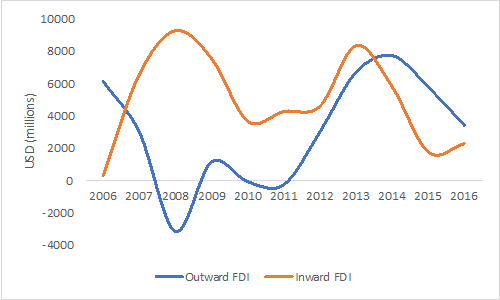

Investor confidence had waned under Zuma, affected by stringent black ownership targets, slow economic growth, political uncertainty, and the country’s declining credit ratings, which plunged into junk status in April 2017. Both inward and outward FDI suffered; inward FDI declined sharply upon Zuma becoming ANC president in December 2007, and is yet to recover to pre-Zuma levels (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: South Africa’s inward and outward FDI

A Ramaphosa resurrection?

Ramaphosa’s business background and pro-industry approach gives investors hope that he can improve South Africa’s investment environment and economic prospects. His talk of potential economic reform at Davos was cheered by financial markets. Indeed, his first days in office have seen him stave off legal action from the Chamber of Mines and others by giving assurances that a new Mining Charter will be developed in a consultative manner with all stakeholders, reflecting the interests of the industry and the country.

In his first major speech on Friday, Ramaphosa vowed to clamp down on corruption in public institutions. Righting South Africa’s ship will, however, take hard work and political will. Zuma’s watch saw corruption become deeply entrenched in the government. There have also been systematic attempts to erode the independence and functionality of many public institutions, including the national prosecuting authority and independent investigatory agencies. Ramaphosa will need to act fast to show that he is both serious about rooting out corruption and capable of doing so.

Indeed, he is expected to soon purge the Cabinet of Zuma cronies and others tainted by corruption allegations. For example, Mosebenzi Zwane, the current Mineral Resources Minister, was the Free State’s agriculture head at the time of the Vrede Farm scam. He was also purportedly the instigator of the Vrede Farm scam, which is indicative of the level of corruption within Cabinet. In the same vein, Ace Magashule, ANC Secretary General (and National Executive Committee member) is Free State Premier and similarly tarnished by the corrupt dairy plan.

A new ANC for a new South Africa?

Ramaphosa and the ANC are now in rebranding mode. Ramaphosa undoubtedly hopes to shelve the blame and scandal that has followed him since the Marikana mine massacre in 2012. As a shareholder in the Lonmin company, the mine’s owner, he had called for police action to end an unprotected mine strike, resulting in the deaths of 44 mine workers, 34 of whom were shot by police. Successfully reforming South Africa’s leadership would help temper his reputation.

The ANC is taking credit for ridding the country of Zuma, but has so far failed to also take responsibility for having defended Zuma in numerous votes of no confidence, and having stood by as he opened up South Africa’s public institutions to corruption and state capture. Nevertheless, if the ANC’s rebranding efforts succeed, opposition parties stand to lose, as a reformed ANC promises to undercut opposition parties’ electoral gains in next year’s general election.

For now, South Africans can breathe a sigh of relief that Zuma’s presidency is over and be tentatively optimistic that Ramaphosa’s leadership may bring much-needed reforms. The next general elections, to elect national and provincial legislatures, will be held in 2019. The ANC have maintained a legislative majority since 1994, although the 2016 municipal elections saw the ANC losing control of several major metropolitan areas, including Johannesburg and Nelson Mandela Bay, to the opposition Democratic Alliance. Continuing to cultivate a viable opposition and an active electorate will be crucial to ensuring greater accountability and political competition at all levels of South Africa’s government.