The resilience of informal labour markets: Insights from Uganda

While the lockdown in Uganda resulted in a large but temporary shock to SME activity, mature labour relationships were highly resilient to the lockdown, and a large share of workers were able to temporarily engage in alternative income generating activities during the lockdown.

On 30th of March 2020, the Government of Uganda implemented a hard lockdown for a 14-day period: all non-essential businesses were temporarily closed, public transportation was halted, and curfews were imposed. Lockdown restrictions were further extended through a series of (unforeseen) extensions on April 21, May 4, and May 18. These measures were partially eased from May 26 onwards, when shops were permitted to reopen, although restrictions on mobility continued to be in place until July of that year.

The stringent restrictions through April-June 2020 significantly impacted the informal economy, where workers are especially vulnerable given the lack of access to formal contracts, employment benefits or protection. While firms were shut down, there were reports of workers leaving cities, traveling back to their home villages, and turning to alternate income sources such as farming. This raises the concern that the impact of the lockdown might have been particularly severe in informal labour markets. Through phone interviews with a representative set of firm owners and employees, we study the impact of the economic shutdown on employment relationships in the informal economy.

Our starting point is a representative survey of 1,115 small and medium-sized firm owners, and their informal employees in urban and semi-urban Uganda that we conducted in 2018-19. Our survey covered firms in carpentry, welding, and grain-milling. As we had phone contacts for both firm owners and employees, we re-surveyed this sample in late 2020 to construct a labour force panel survey that allowed us to track each firm and worker relationship over the lockdown period. This data allowed us to study which pre-existing relationships were disrupted and why. For instance, if a worker was not rehired, we examined whether this is because the firm did not have enough work or hired replacement workers. Documenting the resilience of informal labour relationships and the extent to which informal workers were recalled by their employers after the lockdown ended is crucial to understanding the aggregate social and economic impacts of the lockdown, and formulate policy responses to aid the path to recovery, such as considering subsidies for firms versus income support for unemployed workers.

The lockdown was a large but temporary shock to SME activity

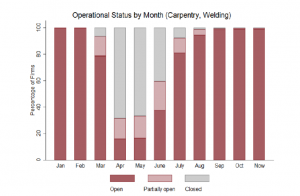

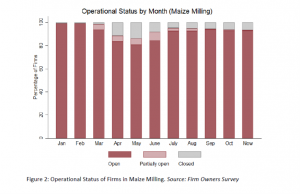

Consistent with policy restrictions in Uganda, Figure 1 shows that most firms in the carpentry and welding sectors closed operations between April and June 2020. We observe heterogeneity in patterns of temporary firm closure by sector as the grain milling sector was not required to halt operations during the lockdown period since it was classified as an essential sector (see Figure 2). Notably, we find that 98.7% of firms that shut shop during lockdown have now resumed operations. The extent of firm closures during the lockdown, coupled with the resumption of business reported since the easing of restrictions, suggests that the lockdown was indeed a large but temporary shock to SME activity in Uganda.

Figure 2: Operational status of firms in carpentry and welding

Figure 2: Operational status of firms in maize milling

Source: Firm Owners Survey

Mature labour relationships were very resilient to a large economic shock

The panel survey of employees allows us to track firm and worker relationships with precision before, during and after the lockdown period. It should be noted that these relationships represent a selected sample of higher tenure employees who have remained employed at the firms in our sample since we first interviewed them in 2018-19. Consequently, our findings from the employee panel (for example, employment status, worker earnings) are representative of relatively high-tenure employees, rather than of the average employee.

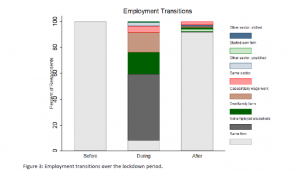

We used the employees survey to document the extent of disruptions, separations and re-matching after the lockdown. Figure 3 confirms that the lockdown provided a large shock to labour relationships – approximately 92% of those employees who we surveyed in 2018-19 and who were still employed at the same firm in March 2020, were let go by firms that closed operations during this period. This raises potential concerns related to income losses, potential scarring, and human capital depreciation over periods of inactivity/alternate unskilled employment. However, we observe that of the employees that were let go, almost half found alternative income sources through casual/daily wage work or agriculture during the lockdown, and 91% were hired back by the same firm after the lockdown. We also observe that workers find employment in similar sectors (shown in red) both during and after the lockdown, which further suggests that human capital deterioration is not a predominant concern in our setting.

Sample: Employees surveyed in 2018-19 who were employed at the same firm before the lockdown. The figure shows the evolution of these relationships over the lockdown period.

These results confirm that mature labour relationships were highly resilient to the lockdown and highlight how a large share of workers were able to temporarily engage in alternative income generating activities during the lockdown.

Using data from the firm owners’ survey, we find that the retention rate of all workers within a firm (not just higher tenure ones) is 76%. This implies that labour relationships are resilient overall, with resilience being particularly strong amongst mature (higher tenure) firm-worker matches.

Firms and workers have experienced a significant drop in earnings

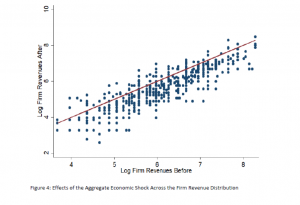

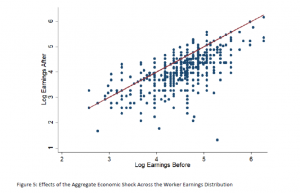

The aggregate shock from the lockdown resulted in a significant change in the economic environment for both firms and workers. We find that: (i) firm size decreased by 3.8% on average, and (ii) both monthly firm revenues and worker earnings are still down by 30% compared to their pre-pandemic levels. These trends are consistent with the general economic downturn and drop in consumer demand in Uganda. Trends in the distribution of the log of firm revenues and worker earnings before and after the lockdown are shown in Figures 4 and 5, respectively. The two scatter plots (and 45-degree line shown in red) demonstrate that the impact of the economic shock has affected firms and workers across their respective earnings’ distributions.

Figure 4: Effects of the aggregate economic shock across the firm revenue distribution

Figure 5: Effects of the aggregate economic shock across the worker earnings distribution

Conclusion and future research

Informal labour relations in small and medium enterprises are strong. A lack of formal contracts does not hinder the reemployment of workers who found alternative sources of employment or moved to their home villages during the lockdown. These relationships appear to be valuable for both firms and workers. Through further data collection and analysis, we aim to study the drivers of firm and worker attachment – for example, to disentangle whether relationships survive due to the strength of relationship capital (firm-specificity of skills, teamwork, communication) or simply because it is too costly to recruit replacement workers due to search and information frictions. Answers to these questions are informative for policy as they speak directly to the efficiency of informal labour markets, and the incentives of firms and workers to invest in skills.

This blog explores insights from this IGC project.