Should electricity be a right?

The question ‘is electricity a commodity or a public utility?’ is thought provoking. A related question is if electricity should be a right and what does it mean. Does it mean people have the right to use as much electricity as they want and at what price? Or should a basic minimum quantity of electricity be available to all irrespective of their ability to pay?

The discussion of the theme “Should electricity be a right?” was held at the IGC India Research Conference on 10 September 2019. The panellists included Robin Burgess (Director, IGC and Professor of Economics, London School of Economics and Political Science), Anant Sudarshan (Executive Director-South Asia, University of Chicago), Michael Greenstone (Milton Friedman Professor of Economics, University of Chicago), and R. Lakshmanan (Executive Director, Rural Electrification Corporation Ltd). The discussion was moderated by Rahul Tongia (Fellow, Brookings India).

Should electricity be a right?

Introducing the issue, Rahul Tongia remarked that thinking about whether electricity is a right is relevant in framing how the electricity is regulated and governed, which then determines how cost effective it is. This tension – about how we govern, regulate, price, control, and ration it – is really at the heart of a lot of issues of development.

The event was held in New Delhi ─ by most natures, the richest state in India ─ which provides among the highest tax-payer subsidies for electricity in the country. A month back the government announced free electricity up to 200 KW hours per month.

The consequences of viewing electricity as a right

Robin Burgess’s ideas broadly revolved around arguing that electricity is not a right. Electricity is needed however to operate any modern productive activity thus having direct links to growth. Lack of access or very patchy supply of electricity constraints anybody’s ability to take part in any productive activity.

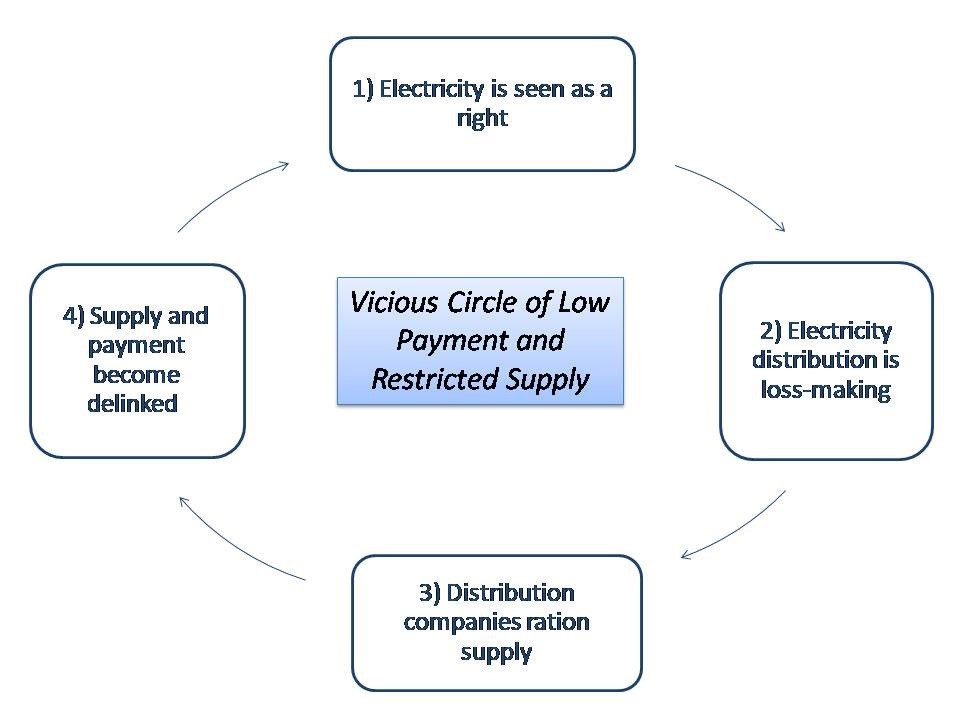

In developing countries like India, the distribution companies face losses due to several reasons including – transmission & distribution losses, people not paying for their electricity, and people stealing electricity. He believes the root cause of this is that people view electricity as a right. Due to this, a ‘vicious cycle of low payment and restricted supply’ is formed as shown in the figure below.

The losses that electricity distribution companies face result in rationing of electricity, i.e. nobody ends up getting 24 hours of electricity. Hence, he believes that to expand access, it is necessary that these losses reduce.

Otherwise, the State has to ultimately bear the losses of the distribution companies, and so what is observed is something typical to mortgage – there is simply no relationship between how much one pays as a feeder and the hours of electricity they receive. That reaffirms the view that why on earth would anyone want to pay for electricity.

Two possible ways to break this vicious circle are: Government’s commitment to treating electricity as a commodity, and improved supply of electricity.

Incentives to improve electricity supply and reduce distribution losses

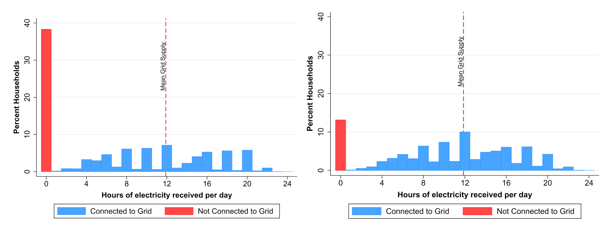

Anant Sudarshan highlights India’s amazing progress in expanding the access to electricity in the last few years. However, his research shows that houses still don’t receive adequate hours of electricity per day as can be seen in the graphs (from their research) below.

Through a randomised controlled experiment conducted in eight districts of Bihar, Sudarshan et al. aim to understand how to minimise losses through improved rationing of power supply. Two groups were assessed ─ a ‘control’ group where the supply is uniform across all areas and a ‘treatment’ group where supply is based on their revenue performance. Following graph exhibits the results of the study which imply that revenues generated from the treatment group were higher than that from the control group, except during the time of assembly election and at the dispensation of the scheme. With the implementation of this idea/project, some increase in revenue of the distributors is found since electricity is sent to the right people.

Estimating demand for electricity in rural Bihar

Michael Greenstone remarked, “the world has no examples of countries achieving high levels of living standards without consuming lots of energy”. Greenstone et al. have tried to assess the situation of electricity and its supply in rural areas of India. They have found large shifts in electricity landscapes happening in rural areas around the world.

- There has at least been an incredible increase in connections if not the electricity flowing to the connections.

- The unprecedented and unpredictable decline in solar costs has raised the possibility that solar energy can be part of the answer especially in rural areas, where it can be expensive to connect people to the grid.

- A remarkable increase in the income in India and many other countries over the last several decades.

They tried to estimate individuals’ demand for electricity and provided the following four takeaways for rural Bihar.

- The price sensitive consumers of Bihar respond adversely to an increase in price of the grid service, which leads to low surplus from electrification.

- If the grid were removed, it would reduce government’s popularity but may not affect households much because they would switch to solar energy leading to only a modest decline in electrification.

- The value of solar grid’s availability depends on the presence of the traditional grid and solar prices.

- The traditional grid has advantages in terms of avoiding intermittency and greater load allowing for more substantial appliances.

A practitioner’s view about why people don’t want to pay

- Lakshmanan questions the quality of electricity access after acknowledging its expansion in India. He believes what is essential for an economy is a good quality, reliable, and uninterrupted power supply. Speaking on losses, as a practitioner in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, he observed that expanding access to areas that are already loss making will only exacerbate the losses, unless some preventive steps are taken in advance. According to him, there are simple reasons why people don’t pay for electricity:

- The week billing or metre-monitoring system that gave people irregular bills, once in 6 or 8 months, would pile up to a huge sum. In such cases, even if people might be willing to pay they may not have the ability to pay.

- The bills that were served were incorrect, inflated or wrong leading to distrust among people, and hence their justification to not pay them.

- People got 6-8 hours of electricity with low voltage levels and multiple interruptions, making them wonder if they were receiving any electricity at all.

In Bihar, the South Bihar Power Distribution Company started working on improving the quality of power supply which resulted in 18-20 hours of better quality power supply in rural areas. They also brought in a new IT platform for regular/monthly billing, this lead to an increase in revenue by around Rs. 100 crores in just eight months.

According to him, two possible solutions to make electricity supply more sustainable and viable going forward are:

- Prepaid billing, i.e. if you don’t pay you don’t get electricity; and

- Direct benefit transfers for providing subsidies.

Concluding remarks

Is it right to attribute the losses of distribution companies only to the poor for stealing electricity and non-payment of bills ─ or should the distributors and governments be held equally responsible for poor billing systems and low quality supply? Why can’t poor save every month for bills that pile up? The answer to this may lie in understanding the decisions made by poor households.

The poor consume a large share of their income which reduces their capability to make any additions to their consumption basket. They live under debt due to several reasons and its non-repayment often leads to serious consequences. It forces them to cut short several important expenses, including those on education, medical care, and electricity. Electricity has been a luxury for a really long time and clean energy more so as only those who can afford it get it. However, imagining a life without electricity is not possible today.

Therefore, a relevant question in this debate of electricity as a right is, how access to clean energy can be provided to the marginalised sections at a price that they will be willing to pay, which is also an agenda of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Kennedy et al. (2019) have found a strong positive relationship between quality of power supply and people’s willingness to pay for it. As pointed out in the discussion above, improving the quality of access will also result in setting off the losses of distribution companies. Azad and Chakraborty (2018) have proposed charging carbon tax to those whose carbon footprint is beyond a threshold limit and making energy free, up to a limit, for the poor.

Robin Burgess has suggested policy measures such as rationalising subsidies, implementing payment-based supply, incentivising bill collectors, using technology for better monitoring and enforcement systems, and bringing in alternatives like off-grid solar to solve the problem of restricted power supply.

Finally, a host of behavioural interventions can be taken to improve people’s willingness to pay and reduce distribution losses.

Watch the entire event session here: