Technology and property tax: Raising city revenue in Kampala

Recent technology has proved effective in expanding the city’s tax base but requires up to date data and is no substitute for supportive policy and legislation.

Property taxes are a hugely important potential source of revenue for cities. Faced with limited municipal revenues and rapidly growing populations, taxes on the value of land and property can offer a significant source of funding for cities to provide local services and to tap into financing for larger investments. Kampala, the capital city of Uganda, is no exception here – property taxes made up over 30% of the Kampala Capital City Authority’s (KCCA’s) own source revenues (OSRs) in 2018/19.

To economists, the appeal of these taxes goes beyond their significant potential for revenue generation. Rising urban land and property values over time are largely driven not by private investments in this property, but by public investments in infrastructure like roads and schools, and by rising demand for space in a city due to urban migration.

By taxing properties, cities are able to get a return on the investments they have made into urban areas. Revenues from these taxes can be reinvested into the city, raising property values further – unlocking a virtuous cycle of urban investment.

Though promising in theory, implementation of these taxes is a different story. In addition to obvious political challenges to these taxes from wealthy and often politically powerful landlords, the administration of these taxes is extremely challenging. Many city governments are faced with outdated property rolls that limit the tax base, and use valuation systems that are unable to accurately and fairly track property values.

Recent reforms in the city of Kampala highlight the promise of technology for leveraging property taxes – and its limits.

Tax revenue and technology

Since its establishment in 2011, the KCCA has placed a strong emphasis on raising tax revenues - and on leveraging technology to do so. The introduction of an automated system of revenue collection, eCitie, in 2013, allowed the city to move away from manually recorded tax records to an online system that provides up-to-date information on billing and payments to both taxpayers and the city authority. Due in large part to the introduction of this system, revenues in the city increased by over 100% between 2011/12 and 2014/15 (Kopanyi, 2015).

The successes of these initial reforms soon prompted the city to consider ways it could leverage one of its main revenue sources – property taxes. In Kampala, where land ownership is in many cases unclear, this tax is applied to the rental/business income of buildings - income flows that are more easible taxable than property values.

Until 2014, a key source of revenue loss in the city was an out-of-date property tax roll (the last version was completed and valued in 2006). Not only were dramatic increases in property income values over this period not being recorded and taxed, but all properties that had been built during this period were not included in the tax net.

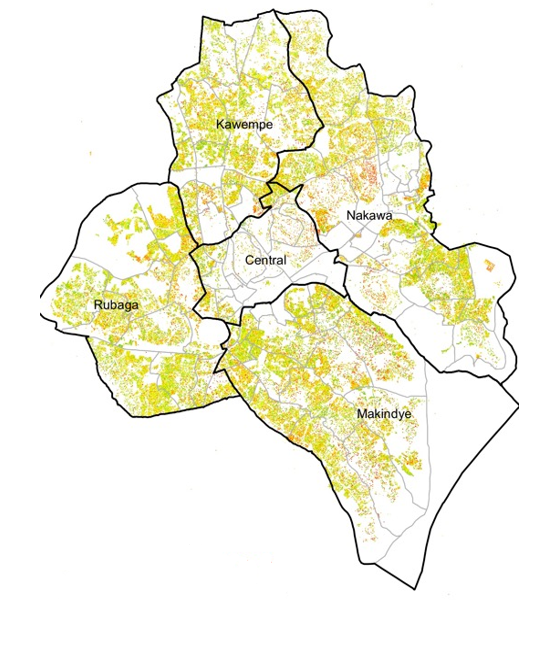

Figure 1: GIS data on properties across Kampala

Through an ambitious project funded by the World Bank, the KCCA tackled this issue by assigning addresses to over 350,000 formal and informal properties in the city between 2014-2019. As part of this exercise, Geographic Information System (GIS) and ownership data was collected on all properties in the city, as well as over 50 features affecting property incomes.

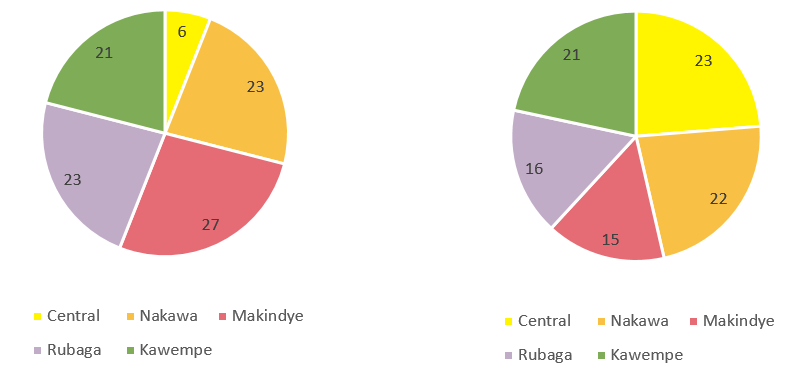

These reforms have increased revenues considerably: between 2016/17 and 2017/18, with the introduction of updated Central division records, property contributions to OSRs increased from 19.8 to 29.3%. At the same time, this comprehensive data collection offers a rich source of information to understand property tax potential and areas for policy reform.

Figure 2: % properties by division Figure 3: % potential revenue by division

Future reforms: Mass property valuation

Now that the KCCA has valued all properties in the city, how can they keep this record up to date to accurately track rising values of different properties and their incomes over time? Given fiscal constraints, it is unlikely that the city will be able to regularly repeat the recent exercise of individually valuing property incomes. As such, the KCCA is now exploring the potential of mass valuation models. Using these, the city may only have to update valuations for a small representative sample of properties, and use these to predict all other values in the city.

Initial analysis of the performance of some mass valuation models when compared with individual valuations highlight two key lessons:

- Simplicity is key: models that include more features affecting property value do not significantly add to the accuracy of predictions.

- Missing data: By contrast, the differences in accuracy that come from having missing data are significantly greater than differences resulting from adding or subtracting property features from the models.

As such, it seems to be more important to focus on collecting more comprehensive data on a smaller number of variables for the purposes of property valuation.

Conclusion: Addressing ongoing challenges

Despite its benefits, Kampala’s experience highlights two key challenges when leveraging technology to enhance property taxes:

1. Digitisation is only as good as your data.

Even if mass valuation models allow cities to update valuations over time, the promise of these models is only as good as the underlying data. The question facing the KCCA now is

how to keep the comprehensive database of ownership details and property characteristics up to date over time. This is by no means an easy task.

One key reform being undertaken that may be able to help with this is the digitisation of building permits. The city is planning to link this to property tax collection, so that as soon as a permit is approved, this new property can be added to the tax roll for potential taxation.

2. Technology is no substitute for supportive policy and legislation.

Another issue facing the KCCA is that, despite technological improvements to enhance convenience, limited means of tax enforcement means compliance is still low. If a taxpayer fails to pay their taxes, the KCCA can take them to court, but inefficiencies in court processes make this an empty threat.

While digitisation can enhance the convenience of tax payment, overall tax collection requires:

- Laws to provide effective tax enforcement – including, for example, the ability to seize property or to implement fines for late payments.

- Supportive policies to improve voluntary compliance with property taxes. Property taxes are always going to face resistance from taxpayers – but efforts to more closely link taxes to investments in a city, for example, can encourage taxpayers to see these taxes not as a burden but as the legitimate price of goods and services.

Without these, the gains from technological improvements may quickly run out of steam.

Editor's note: A policy note from this project can also be found here.

References

Collier, P. et al. (2018). Land and property taxes: Exploiting untapped municipal revenues, the International Gowth Centre, Cities that Work Policy Brief. Accessible: https://www.theigc.org/publication/land-property-taxes-exploiting-untapped-municipal-revenues/

Kopanyi, M. (2015). Local Revenue Reform of Kampala Capital City Authority, the International Gowth Centre, C-43306-UGA-1. Accessible: https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Kopanyi-2015-Working-Paper-1.pdf