Tracking constraints to micro-enterprise growth in Kenya and Uganda

Existing surveys that aim to measure and track barriers to business growth often under-represent micro-enterprises and small informal firms. Our pilot, which targeted a sample of small scale entrepreneurs in Kenya and Uganda in a survey conducted by phone, suggests that such enterprises may face a very different set of constraints to growth. This exposes a potential evidence gap in the type and nature of constraints faced by micro-enterprises.

Entrepreneurship for large versus small firms: Existing data

Business growth and entrepreneurship form a crucial part of a country’s economic development process. Larger-scale businesses often contribute either by generating mass employment opportunities or by increasing the demand for higher levels of skill and education. Smaller, or rather, micro-businesses cater to similar economic outcomes, but in a very different way. For instance, these businesses act as alternative income generating activities for the low-income segment of the population.

Prominent existing survey data on constraints to business growth focus either on large firms or on administrative processes:

- The World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys (WBES) focus entirely on formal firms, mostly those with more than five employees, and those in the manufacturing or services sectors.

- The World Bank’s Doing Business Indicators (DBI) supply macro level indicators for each country and equally suffer from well-known issues (see Besley 2015). It is not based on the actual experiences of firms, and also only targets large, formal businesses in select urban areas.

The study: Surveying small-scale entrepreneurs on their constraints to growth

We targeted small-scale entrepreneurs in a pilot in Kenya and Uganda, covering both formal and informal businesses, surveying the key constraints to growth they encounter. We find several discrepancies in the descriptive results when compared to the WBES and DBI data across various topics.

It should be kept in mind that surveying both formal and informal firms is fundamentally different from the WBES and the DBI because they do not cover informal firms. In fact, our sample mostly comprises informal firms. This explains most of our sample reporting registration processes as a challenge.

Survey findings and data discrepancies:

- Take up of credit: In our sample, around 90% or more respondents in both Kenya and Uganda reported not trying to take a loan, whereas in the WBES sample, between 40%-50% of respondents reported not needing a loan.

- Defining access to credit: The DBI collect data on credit information and credit bureau coverage, which are indicators that do not reflect informal lending mechanisms or access to credit organisations available to small firms and entrepreneurs, such as Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs) and Savings and Credit Co-Operative Societies (SACCOs).

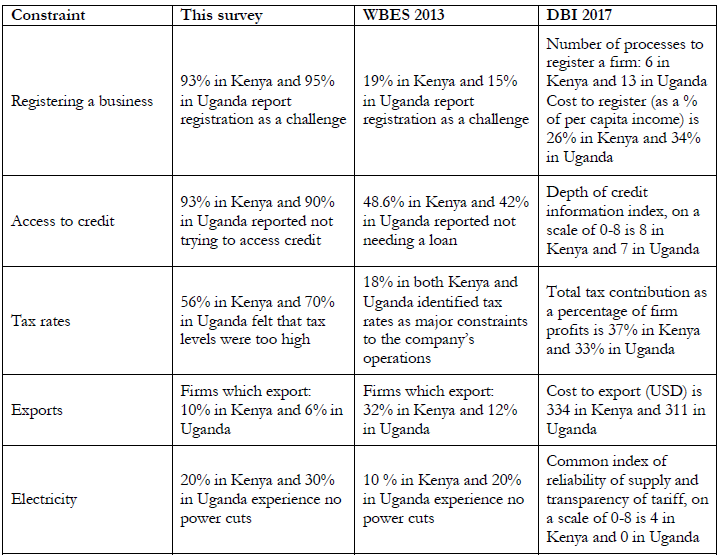

Table 1 presents some of these differences across the three survey methods. Interestingly, we find that some of these measures might also be complementary to each other in weaving together a policy agenda. Consider for example, electricity supply: The similarity of measures (in relative terms) from each of these three surveys suggest that power supply in both countries is unreliable across all types of firms.

Why do constraints matter for economic growth?

Many poverty graduation programmes and models of microfinance are based on encouraging women to participate in entrepreneurial activities. To build on the effects of these programmes, it is important to understand the constraints faced by these entrepreneurs.

If we consider entrepreneurship as an income diversification mechanism for low income households, such set up costs (both monetary and in terms of time) coupled with the lack of easy access to credit may hinder economic growth. This is due to constraints on: Entrepreneurship, transitions from agriculture to self-employment, and business growth for low-income households in these countries.

Table 1: Comparison of Summary Statistics across this project, WBES and DBI data

Recommendations: The effectiveness of phone surveys

This pilot offers an alternative methodology to track constraints to growth for micro-enterprises, which is both cost-effective and can allow for much larger sample sizes. These surveys were conducted using interactive voice response (IVR) technology via mobile phones. In contrast to the WBES and DBI, which interviews managers and firm executives from about 700 firms each in Kenya and Uganda, our survey was able to cover 3300 entrepreneurs.

Coupling cost-effectiveness and greater reach, these phone surveys can be administered much more frequently, thus generating a wealth of data that can closely track small businesses. With mobile penetration growing in developing countries, our hope is to expand these surveys to other countries.

References:

Besley, T (2015). “Law, regulation, and the business climate: The nature and influence of the World Bank Doing Business project”, Journal of Economic Perspectives.

World Bank (2017). Doing Business Indicators. Accessible: http://www.doingbusiness.org/

World Bank (2013). World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys. Accessible: http://www.enterprisesurveys.org/