Trade, informality, and corruption: Evidence from small-scale traders in Kenya

The COVID-19 pandemic has induced vast trade disruptions that have stunted firms’ sales, profits, and growth, particularly for small-scale traders. While many formal borders closed, small-scale traders crossing official borders must increasingly rely on informal border crossings to make a living. In Kenya, we surveyed small-scale traders to analyse their cross-border trade patterns following the formal border closure, the increasing costs associated with informal crossings, and the interdependencies that exist across formal and informal crossings.

For a complete assessment of trade across African countries, informal cross-border trade[1] must be considered. Trade qualifies as informal if traders do not use the official border crossing points, and instead use alternative side routes to avoid taxes and/or official procedures2. A large proportion of informal trade is carried out by small-scale traders who cross the border multiple times a week to source products, such as agricultural goods. Although informal trade is thought to be large in magnitude[2], the lack of records in official trade statistics results in little data and evidence on these small-scale traders.

COVID-19 induced border closures: what happens when the formal border closes?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments imposed temporary restrictions in an effort to limit the spread of the virus, resulting in the closure of many formal border posts. While trucks transporting essential food items were allowed through, many small-scale cross-border traders, usually operating on foot, bikes, or motorcycles, were not. The closure of an official border is a unique event and provides the opportunity to look at how interrelated formal and informal trade are and to reveal characteristics and behaviours about markets and traders. In this context, we use the border closures between Kenya and Uganda to study the interdependencies between formal and informal trade for Kenyan traders.

In collaboration with a team of surveyors, we collected high frequency data from a representative sample of 1,100 small-scale traders located in Kenyan markets situated within 40 kms of the Kenya-Uganda border. This project focuses specifically on traders who either trade agricultural goods (grains, vegetables, fruit, fish) or shoes and clothing. We carried out over 15 rounds of surveys (in person and via phone) from February 2020 to the end of 2021, which allowed me to document changes occurred during the pandemic. Most of the findings outlined here focus on February 2020 to November 2020[3].

Who are small-scale traders?

Prior to the proliferation of COVID-19 (at baseline, February 2020), 80% of traders in the sample were agriculture traders and 20% were traders who trade in shoes and clothing. An overwhelming majority of small-scale traders are women (80%). Despite their businesses being relatively small, trading is a complex activity: traders must optimise which goods to trade, where to source products, which markets to sell in, how often to stock up, which trade route/border crossing to use, and more. The data collected shows that small-scale traders are opportunistic: they often trade in multiple goods depending on profit opportunities, often trading in 3-4 types of goods simultaneously. They source products from 1-2 markets, sell in 1-2 other markets, and stock up multiple times a week. 45% of traders operate along domestic supply chains, i.e. buying/selling their goods in Kenya (domestic traders), while 55% cross the border to source products in Uganda (cross-border traders).

Interestingly, not all cross-border traders go through the official border post; a majority of them (63%) instead use informal routes usually located on either side of the official border post. This allows them to avoid taxes and tariffs[4], quality control, and other bureaucracy required at the official border posts. Trading through informal routes, however, doesn’t eliminate all border costs. Police officials have strategically positioned themselves at the main informal crossings to collect bribes against passage. Bribes paid vary by quantity of goods transported, by type of goods, as well as by trader[5].

Border closures disrupt trade, sales, and profits

Between April 2020 and October 2020, small-scale traders could no longer cross the official border post between Kenya and Uganda due to border restrictions. When suppliers are no longer able to reach, how do traders and markets react? I find that over the course of the first month, the pandemic restrictions forced over 20% of traders to shut down their business, but many recovered and roughly 90% of traders are in business in 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percent of traders who traded in the preceding two weeks in 2020

Note: Percent of traders surveyed who reported trading in the preceding two weeks, by month of operation.

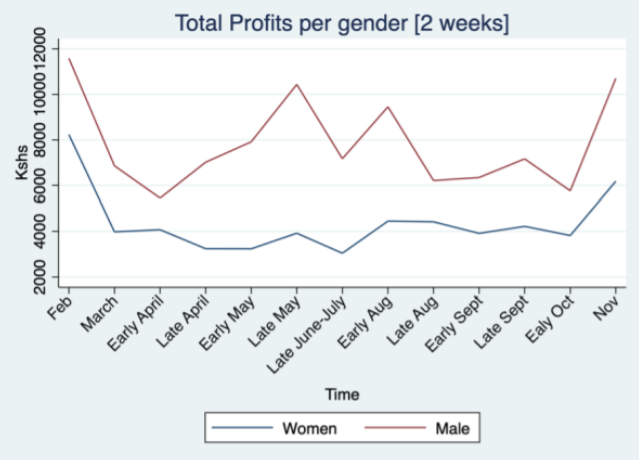

Sales and profits also suffered during the first few months of the pandemic with average sales falling by 37% and profits by 54% compared to pre-pandemic levels. Traders report that COVID-19 restrictions are the main reason for this decline, rather than possible seasonality patterns. However, traders are differentially affected by the pandemic. For example, Figure 2 shows that traders’ decline in profits disproportionately affected women who continue to have lower profits and recover more slowly than men, despite the fact that women are more likely to stay in business.

Figure 2: Total profits by gender

Note: Total profits in the preceding two weeks, by gender. Profits reported in Kenyan shillings.

Overall cross-border trading declines, while informality increases

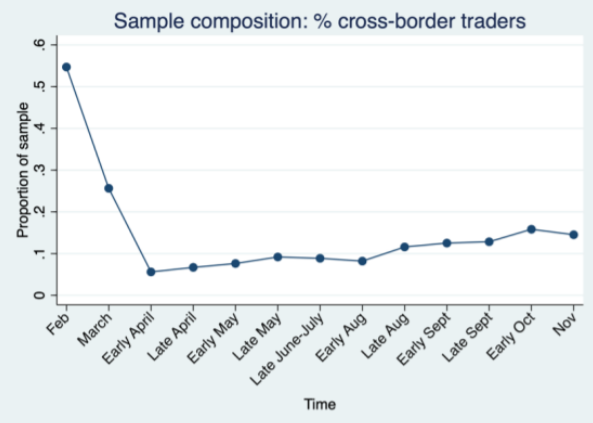

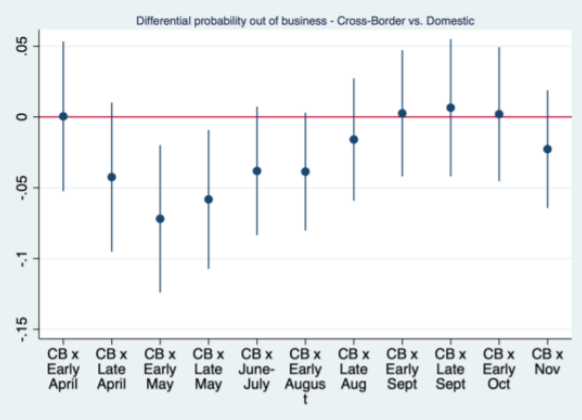

Traders’ resilience stems from their ability to adapt to shocks. Small-scale traders diversify across types of goods and regularly switch goods within an industry (for example, within agriculture goods). However, the costs of switching across industries (for example, from shoes and clothes to agriculture) are significantly higher and traders prefer to temporarily shut down their business rather than switch industries. Variations in resilience also rely on traders’ ability to find new supply chains and/or new trade routes. We would expect cross-border traders to be more affected by the border restrictions than domestic traders as border closures completely disrupt their supply chains. Whereas 55% of traders were cross-border traders in February 2020, only 6% remain in April and 15% in November 2020 (Figure 3a). This shift in sample composition, however, is not due to cross-border traders going out of business, but instead from them switching to domestic suppliers. Figure 3b shows that despite having to find new suppliers, cross-border traders (CB) are surprisingly less likely to be out of business compared to domestic traders.

Figure 3a: Share of cross-border traders in sample

Figure 3b: Differential probability of being out of business, cross-border and domestic traders

Note: Figure 3a shows the proportion of the sample conducting cross-border trade during the study period, reported bi-weekly. Figure 3b shows the differential probability of traders being out of business.

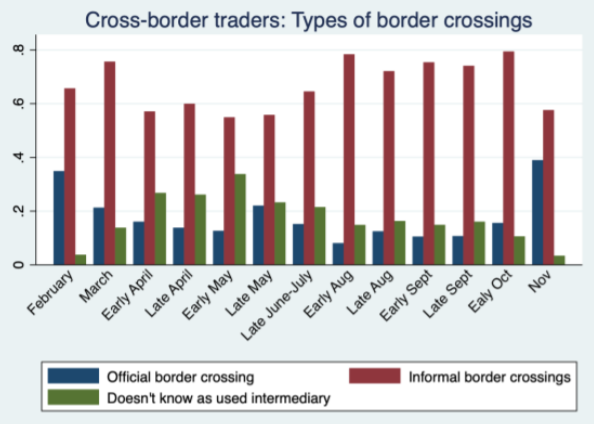

Traders who opt to continue to cross the border switch to informal border crossings. Figure 4 shows that traders rely increasingly on informal trade routes due to the closure of the official border crossing: informal border crossings were used 1.8 times more compared to official border crossings at baseline, compared to 6 times during the closure of the official border.

Figure 4: Types of border crossings used by cross-border traders

Note: Share of border crossings used by type of cross-border trader, by month in 2020.

Corruption increases with border closings

Informal trade plays a role in enabling some cross-border trade, despite border restrictions, providing a way for both informal traders and formal traders to limit business closures and possibly limit price shocks, at least locally. This increased reliance on informal trade (in terms of usage and trade flows) due to the closure of the formal crossing can be related to an elasticity of informal trade with respect to formal tariffs: changes in border costs at the formal border[6] will not only have consequences on formal trade flows but also affect informal trade.

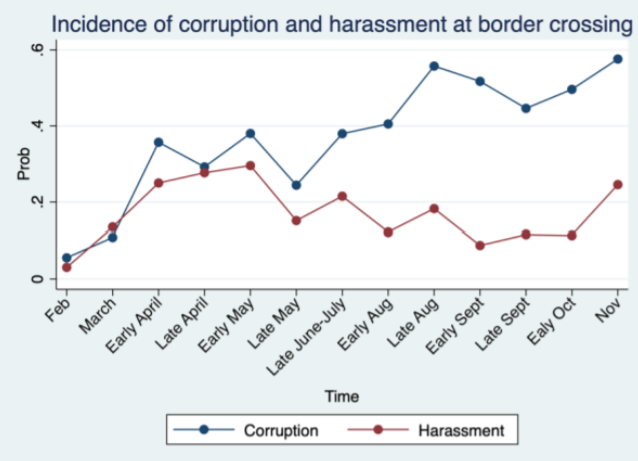

I also find evidence of inter-dependencies between equilibrium costs incurred along formal and informal trade routes. Closure of the border not only pushes traders towards using informal crossings, but also affects the costs of using them. I find evidence of an increase in the incidence of harassment from 3% to 30% after the border closure, a corresponding increase from 6% to 38% in the incidence of corruption, and more than a doubling in the level of the bribes. With the closure of the official border crossing, traders lose one of their main outside options, increasing the police’s bargaining power to request higher bribes, more often (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Incidences of corruption and harassment at border crossing

Note: The probability of corruption or harassment occurring at informal border crossings, by month in 2020.

Conclusions and future work

These findings highlight the importance of considering informal trade when designing policies, despite the difficulty in collecting data. Both formal and informal trade are interdependent: a trade shock or policy change such as a border closure targeted at the formal border crossing will impact usage and trade flows through informal routes. Beyond this, there seems to be an equilibrium in border costs across both sectors: an increase in formal border costs will in turn affect costs at the informal border crossings (for example, bribes and harassment). Other follow-up projects are currently ongoing. Through an RCT, I focus on understanding the role of information in reducing trade costs and how information impacts both formal and informal trade. Another project looks at how bribes are agreed upon and vary by traders’ characteristics.

Editor’s note: The author would like to thank J-PAL & CEGA’s Agricultural Technology Adoption Initiative (ATAI), J-PAL’s Governance Initiative (GI), CEGA’s Development Economics Challenge Award for financial support, and the assistance of the data collection team at Innovation for Poverty Action (IPA).

[1] Informal trade doesn’t specifically imply the goods traded are illegal - for example, many informal cross-border traders trade agricultural goods.

[2] World Bank (2020) report that values and volumes add up to sizable aggregate import/export amounts that can exceed official, customs-recorded trade.

[3] A RCT focused on understanding the role of information in reducing trade costs was carried out in April 2021 and is the focus of another project currently ongoing.

[4] Despite taxes/tariffs being relatively low for agricultural goods

[5] Understanding how bribes are set and vary by traders’ characteristics is the focus of another project currently ongoing.

[6] A border closure would here be considered as an extremely large border cost, for example, an infinity tariff.