Understanding Third Tier Organisations (TTOs) in Pakistan and their role in filling public delivery gaps at the community level

Research into Third Tier Organisations in Pakistan highlights the important work they carry out in spite of a lack of significant government funding.

Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund (PPAF), a not-for-profit, along with its partner organizations has been working on social mobilization and development of voluntary organizations at community level across Pakistan. A well-defined three-tier hierarchal structure is in place with community organizations (COs) at the first tier, village organizations (VOs) at the second and Third Tier organizations (TTOs) at the third. TTOs are essentially volunteer organisations for community-driven development. They help provide representation to around 30,000 people within the Union Councils they are located in, and fill the gaps left by unaddressed community needs. For this reason, TTOs are also known as Local Support Organisations (LSOs). There are around 1,000 TTOs active across Pakistan in the spheres of health, education, microfinance, human rights, community infrastructure, and other sectors.

These organisations do not typically generate revenue and require funds, either through private fund-raising or donors, government, or their Partner Organisations (POs). Leading POs include the National Rural Support Programme (NRSP) engaged with 60% of the TTOs, followed by Sindh Rural Support Organisation (SRSO) (11%), Sarhad Rural Support Programme (SRSP) (8%), and Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) (7%). In particular, POs are the primary support system for the TTOs as they closely monitor and support the aims of the TTOs under their purview to ensure that they operate with as much ease as possible.

Since POs look out for the interests of their TTOs, they provide monetary backing through direct and indirect funding, as well as non-monetary support by way of coordinating their activities across government and line departments. In addition to this, they also supply technical advice or staff trainings when needed. Empowering and working directly with TTOs can help improve government outreach for public service delivery because TTOs have optimal proximity to the needs of the community for the delivery of innovative and tailored solutions.

The Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund

The Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund (PPAF) has been championing coordinated efforts to increase the institutional capacity of civil society organisations at the forefront of ending poverty from the grass root level. To this end, PPAF has secured government and the World Bank’s support in designing and implementing capacity-building development interventions targeting TTOs through their link with a large network of POs.

PPAF has collaborated with researchers from the Lahore School of Economics, University of Oxford, and Duke University to study how these TTOs work and identify ways, using self-reporting and non-financial incentives, to improve their performance. A baseline survey of 850 TTOs was conducted in 2014, collecting data on their governance structures. This included information about their Executive Body (EB), General Body (GB), governance mechanisms, and activities. The survey also recorded characteristics of villages and the work of TTOs in those villages by interviewing village officials. Further, a randomly selected sample of households from 150 Union Councils was also surveyed to record their perceptions about TTOs and the assistance these households have been receiving from TTOs.

The workings of a Third Tier Organisation

Improving access to health and education, and provision of legal support for attainment of human rights, are the main areas of cooperation between the TTOs and the citizens in Pakistan. To successfully execute the agendas for each TTO category, thorough coordination with the government is often crucial, however, not always available. TTOs have to pressurise the government to get their support through sit-ins and meetings.

In general, TTOs require external funds in addition to locally generated funds to cater to the demands of their community, especially for provision of infrastructure and setting up of vocational training facilities. POs and external donor funds help improve the outreach of the TTO receiving it, but almost all TTOs continue carrying out local fund-raising in addition to the external financing they might receive. Even though the majority of TTOs are not beneficiaries of external financing, they continue to utilise whatever resources are at their disposal for community development.

How education levels of TTO management impact outcomes and perceptions

TTOs with less educated Executive Body (EB) members are considered to be less mature and are therefore visited more frequently by social mobilisers so that the PO can oversee their activities from afar, in addition to directly visiting them. Further, TTOs with less educated EB members apply for less funding than their counterparts with more educated members. TTOs with a higher proportion of educated members are perceived to be making more progress in their community-driven objectives as reflected in citizen feedback. This might be unfair because even less educated EB members are extremely proactive in their philanthropic pursuits.

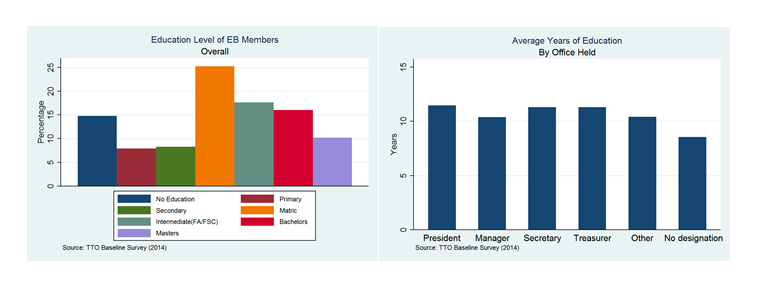

EB positions are not always held by educated members alone. All the major EB offices, including that of president and secretary are held by EB members with average education of 10 years (as shown in Figure 1). This is an encouraging observation showing that a lack of education is not a barrier to participatory civic engagement.

Figure 1

TTOs work in tandem with their POs through actively reporting to them, either verbally or by submitting progress reports on the criteria identified by the POs. It is quite promising to note that TTOs across all regions reported regularly to their POs. More specifically, it was noted that TTOs with a predominance of higher educated members were found to report less frequently to their POs and Punjab is second to Sindh in terms of having a high proportion of less educated TTO members. Punjab has recorded the highest frequency of reporting to their POs, which might have to do with the lower education levels across its TTOs. EB members in all the other provinces are on average twice as educated as the EB members of Sindh.

POs provide training for improving the financial management of TTOs followed by Union Council (UC) plan development with PO respondents reporting that generally participants in these trainings understand the material well. Encouragingly, PO respondents rated around 52% of TTOs performing for the benefit of the people. TTOs perceived to be the worst performing are located in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan.

Further, there is a direct correlation between the level of activity of the TTO and a PO’s contribution in their affairs. This shows that POs either reward TTOs for being more active by providing their all-out support or PO support led to the increased activity of the sponsored TTO.

Are TTOs inclusive of people with disabilities?

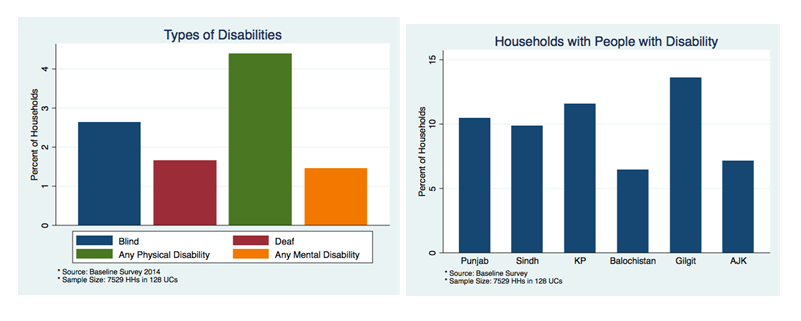

According to the household survey conducted as a part of the baseline survey, people with disability (deafness, blindness, physical, and mental disability) constitute 1.61% of the individuals in the households surveyed. Figure 2 below depicts this information.

Figure 2

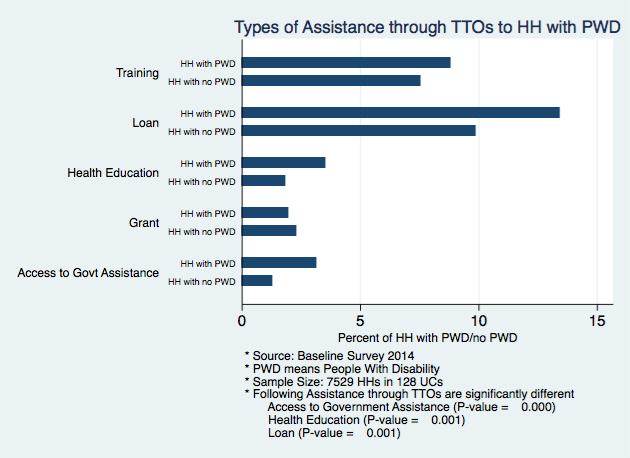

As shown in Figure 3, TTOs target their assistance more than the government towards households with members with disabilities.

While they are assisting more people with disabilities, they are less inclusive of such people in their Executive, Governing, and General Bodies. People with disabilities have to work longer in COs and VOs before they become part of a TTO’s Executive Body. So, PPAF and all rural support organisations should focus on inclusion of people with disability, especially women, in TTOs. People with disabilities are participating equally in TTO meetings, and few report any difficulty in attending these meetings.

Governance structures of TTOs

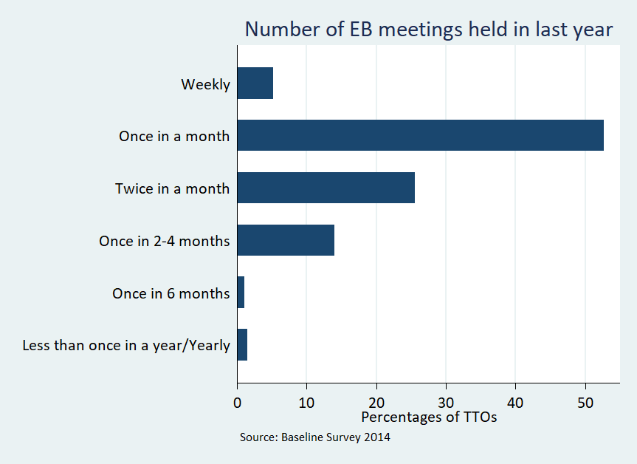

The baseline also explored governance structure of TTOs. Even though PPAF encourages TTOs to hold frequent meetings with their members, this was not reflected in the data. Almost a fifth of the TTOs held only one or no Governing Body meeting in a year. However, members of the Executive Body were more active in a newly established TTO, and the number of EB meetings is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

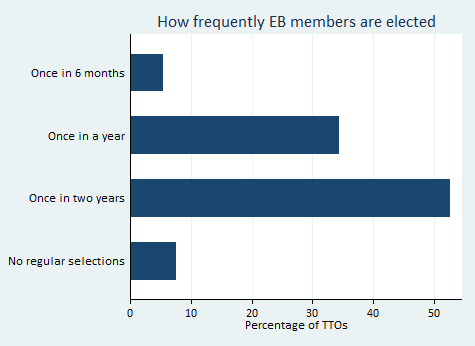

PPAF also encourages a democratic process to elect EB and GB members. However as TTOs age, EB elections are held less frequently and they tend to re-elect fewer of their EB members. The statistics on elections to the EB are presented in Figure 5. A mature TTO could prefer to elect/select new people in their TTO. This could result in more competition per seat for a mature TTO, which is important as it keeps the members motivated to work and give their best. Newly established TTOs tend to re-elect a higher percentage of their EB members as they do not want to lose the benefit of their information and experience.

Figure 5

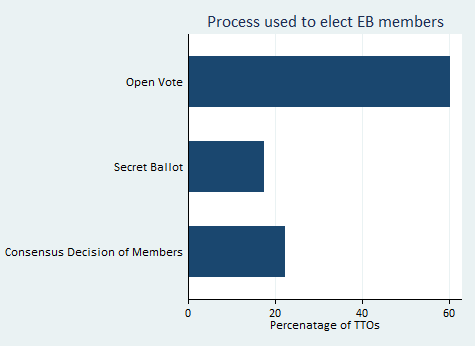

PPAF also pushes for a ‘Secret Ballot’. However, only a small percentage of TTOs practice secret ballot during elections as shown in Figure 6. The most popular form of election/selection among the TTOs remains ‘Open Vote’ conducted through an open ballot.

Figure 6

Where TTO capacity currently stands

The most encouraging finding from the base line survey of TTOs across Pakistan is that TTOs are sustainable irrespective of external funding. This suggests that TTOs remain afloat for the purpose of genuine service delivery and are keen to learn through PO trainings and fully utilise all the support they can get. TTOs in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Gilgit-Baltistan are most active, with Gilgit-Baltistan generating the highest amount of annual income of 650,000 PKR while TTOs in Balochistan are the least active, and also generating the lowest annual income of around 34,000 PKR.

Regions such as Gilgit-Baltistan and Punjab receive much higher international donations, in addition to the high involvement of POs in their TTOs’ development. As a result, TTOs in Gilgit-Baltistan also have the highest accumulation of assets, but it cannot be discounted that these TTOs were among the earliest formed in the country. TTOs in Balochistan have also grown significantly as reflected in their growth of financial assets, but in absolute terms they are still lagging behind other regions.

The way forward

Government funding is not significant enough to account for the growth of TTOs. This is probably because government funding is not based on ground-realities of where funds are crucially needed. This is an area where PPAF can help the government make informed decisions for redirecting its funds to resource-strapped TTOs in the poorest regions of the country. TTO development is largely neglected by the government and needs to be promoted.