Urban data innovations: Three cities showing their smarts

Last year the International Growth Centre (IGC) co-hosted a policy workshop in Washington DC in the United States (US) with the World Bank, George Washington University, and the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) as part of the 6th Urbanisation and Poverty Reduction Conference. The theme was ‘Leveraging new data for better urban management and policies’.

This year, on February 11th and on the other side of the world in Abu Dhabi, U.A.E, at UN Habitat’s World Urban Forum, we are running a training event along similar lines: ‘Data-driven innovation in city governance: exploring global lessons and quick wins’. To give a taster of what attendees can expect, Cities Economists, Oliver Harman and Victoria Delbridge, delve deeper into urban data innovations, and successful new ways cities have been working with data.

Data use and discernment

City leaders require data for effective city management on a daily basis - in forecasting population growth and settlement patterns, weighing up different policy options, and evaluating their effects. The rapid pace of technological innovation is constantly increasing the quantity, quality, and frequency of data available to cities, as well as offering new and innovative ways for the data to be used, stored, and shared.

Cities around the world are waking up to the potential this unlocks, with initiatives such as the Boston Urban Mechanics leading the way with smart parking metres and mobile pothole reporting. Researchers are also exploring the potential of ‘big data’ sources, such as Google Street View to predict housing prices and LinkedIn to assess unemployment.

However, there is a dangerous misconception that ‘innovation’ necessarily refers to the creation of futuristic smart cities. Innovative technology, when applied without a clear purpose, has locked cities into extremely expensive systems that are often unfit for purpose and cannot be maintained without expensive external consultants.

It is, therefore, unsurprising that three quarters of all smart city ‘internet of things’ projects are failing. In some ‘smart cities’, the use of technology is so prevalent it has taken away the key benefit of prosperous city life - human interaction. Songdo in South Korea is such an example, although densely packed with technology it is relatively uninhabited, with occupation at a third.

These examples demonstrate an important principal: Data is only useful so far as it solves an existing problem. In other words, city governments need to establish a clear need for this data before investing large portions of their budget in it. Most developing city governments are still at the stage where getting the fundamentals of data management right can unlock enormous value and allow for innovation that is useful, relevant and represents value for money. We look at three such examples below.

Amman’s urban observatory: Data coordination and sharing

Coordination and sharing of data is one of the first stumbling blocks most cities face in creating an effective evidence base for change. Whilst reams of data from household surveys and administrative data exist in most cities, they are often stored manually, in isolated departments, and with limited accessibility. Recognising this, the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM) has established an Urban Observatory to collect, manage, and analyse the city’s data and information in one place.

One of the major ways data coordination was facilitated was through the establishment of a cross-cutting Geographic Information System (GIS) department. Data gathered from the electricity, statistics, and water departments was brought together and matched geographically - allowing policy to become spatially targeted, rather than separated along thematic lines.

By feeding this information into the Metropolitan Growth Plan, the GIS data led to the city being able to intensify economic activity and densify buildings in certain neighbourhoods. The city has been able to realise some of the promises of proximity – for example, the closeness of citizens enabling the easy communication of ideas.

As with all cooperation, this is still a work in progress. Without existing standardised policies and protocols around data custodianship and sharing, the potential for further advances in urban management have been limited. However, data sources are slowly becoming unified through integration, and data sharing is feeding into and empowering cross-department delivery. The city is becoming smart - not through innovative technology, but data and human collaboration.

Cape Town’s water usage mapping: Data for decision making

Coordinating data and making it available to those who can use it is one critical element in a successful data strategy. But using it effectively for decision making and policy influencing is another challenge entirely.

The City of Cape Town exemplified the potential for new data during the 2016 - 2018 drought, with effective data analysis playing an integral role in dramatically curbing water use from 1.2 billion litres per day to 500 million as the city faced an impending water crisis. This reduction was made possible through two major mechanisms: Improving the efficiency of water infrastructure and a public campaign to reduce citizens’ consumption.

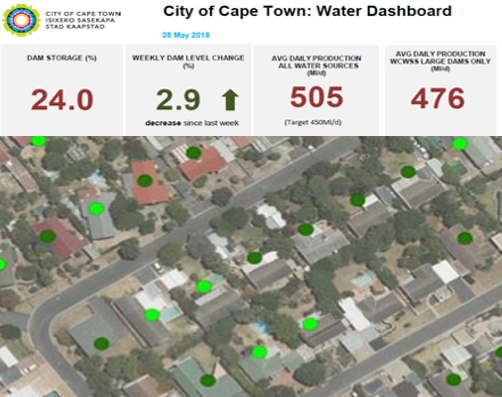

To achieve more efficient water management, the city used timely and detailed information on pipe conditions, water pressure and flow, and consumption to optimise water use and target potential water losses. To reduce consumption, live information on dam levels and water usage collected by the City of Cape Town was made publicly available so citizens could see the extent of the challenge and how their collective behaviour was helping to address this over time.

In an attempt to leverage social pressure and neighbourly competition for behavioural change, the ‘green dot’ campaign used data disaggregated to the household level to indicate the homes that were meeting the water restriction target of 50 litres per person per day – and those that were not. As a result, Cape Town became the first city in the world to reduce its water consumption by 50% in just three years.

[caption id="attachment_31543" align="aligncenter" width="502"] Figure 1: Weekly water dashboard that was displayed on the City of Cape Town’s websites, as well as on other public digital screens, to ensure citizens were informed of relative progress.[/caption]

Figure 1: Weekly water dashboard that was displayed on the City of Cape Town’s websites, as well as on other public digital screens, to ensure citizens were informed of relative progress.[/caption]

Kampala’s insights into informality: Ensuring representative data

Recent reforms to data collection in Kampala highlight that systems and analysis are ultimately only as good as the data you put into them. In many developing cities, available data is largely based on the formal economy. With over two thirds of urban populations in sub-Saharan African countries working in the informal sector, there is good reason to believe that existing data does not represent realities on the ground.

The lack of data on informal settlements and the informal economy distorts a city’s ability to accurately understand the population as a whole and excludes these individuals from the benefits of formal planning and management processes.

To begin to address this problem, the Kampala Capital City Authority made sure to collect detailed information on both formal and informal settlements as part of a recent street addressing and property valuation exercise. The data gathered is being used in both revenue and planning reform, to allow for better informed planning and service delivery alongside a wider tax net.

Conclusion: A realistic data revolution

New technology and new data offer exciting opportunities – but in many developing cities, getting the fundamentals right is just as important. In Amman, making the most of data meant creating a space to coordinate data efforts in once place and ensuring it was more accessible. In Cape Town, it was digitising and leveraging existing administrative data and making the information available for widespread behaviour change. In Kampala, better urban management is happening through incorporating information on a key economic driver – the informal sector - to feed into decision making.

Whilst big data and machine learning pose fascinating potential for the future, the most successful data innovations in cities won’t be driven by external trends, but by realistic and incremental reforms to address existing questions for urban policy. When it comes to a ‘data revolution’, much like Goldilocks, not too much and not too little should be just about right.

Editor’s note: More information on the 10th World Urban Forum in Abu Dhabi can be found here.