Using financial incentives and mobile monitoring to address teacher absenteeism in Uganda’s primary schools

"The challenge: How do we improve accountability of teachers with local monitoring?

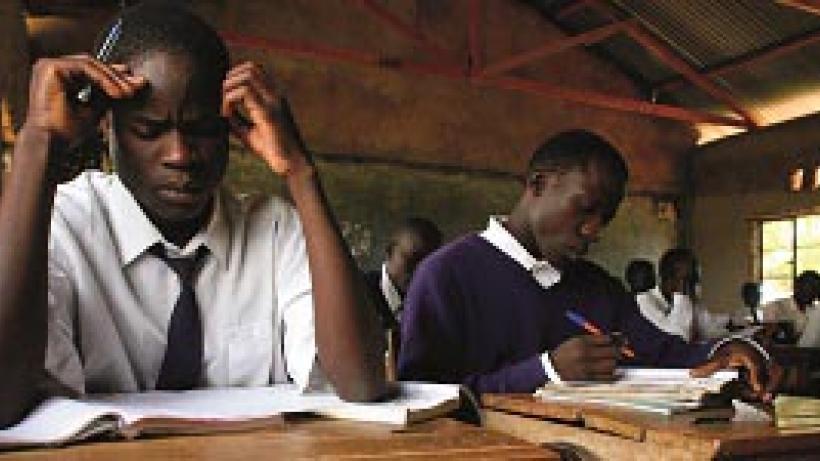

Uganda has made considerable progress in expanding access to primary school in their bid to achieve the universal primary education goal of the Millennium Development Goals by 2015. The number of enrolled primary school-aged children more than doubled to five million after Uganda introduced the Universal Primary Education program in 1997. By 2012, this number had surpassed the nine million mark.

Despite this progress, challenges remain: Low quality is a major barrier to reaching desired learning gains. One key reason for this challenge is teacher absenteeism. Teacher absenteeism is rife in Ugandan primary schools; a recent study led by the World Bank estimated that teachers are absent from government schools 27% of the time. This problem is particularly acute in rural areas, where absence rates rise to 31% in light of limited inspection budgets and high transportation costs that often hinder active oversight by district inspector teams.

In collaboration with World Vision Uganda, we are examining how to increase teacher presence in rural primary schools in Uganda. Recently, two of us (Ibrahim Kasirye from EPRC and Andrew Zeitlin from Georgetown) gave a seminar at EPRC to education policymakers and donors to discuss preliminary results from this ongoing study on incentives, and mobile and SMS-based monitoring of teacher presence.

Results from the first phases of this project suggest three key lessons. First, locally managed incentive schemes can successfully reduce absenteeism when management of these schemes is placed in the right stakeholders’ hands. Second, care is needed with interpretation of the data produced by local monitoring, as it can contain significant distortions, as shown by triangulation of data. This point is important when aspiring to use the data for administrative purposes. Third, involving both parents and head teachers in monitoring of teachers can improve the cost-effectiveness of gains in teacher presence as well as the quality of the data.

Improvements in communications technologies hold great promise as a means to bridge these geographic divides, particularly when combined with local oversight. One such approach has been developed by the Makerere University School of Informatics and Technology, which, together with SNV, developed a mobile-phone-based platform for reporting teacher presence.

Information improvements alone, however, may not be sufficient to bring about behavioural change. Increases to teacher salaries have been proposed by the government of Uganda as a means to motivate teachers to stay in school and teach their pupils. Based on the idea of pay-for-performance, our research studies whether a bonus scheme that rewards teachers for being present, when reported by local monitors via mobile phones, provides a cost-effective means to improving school quality outcomes.

Of course, with incentives attached to information, the threat of biased reporting looms large, and much may depend on who is monitoring. To understand the complex interplay between teacher behaviour, financial incentives, monitor identity and truthful reporting, we have taken an experimental approach.

Our experimental approach

The project works in representative sample of 180 rural, government primary schools, drawn from six districts of Uganda. In each pilot school, mobile phones equipped with software for reporting teacher presence rates to their district education office and other stakeholders on a regular basis were provided to a selected local monitor. In some schools, head teachers were asked to undertake the monitoring, whereas in other schools, monitoring was the responsibility of parents on the school management committee (SMC). Furthermore, we also varied who does the reporting. In two reporting schemes, only the head teacher reported; in two, only one parent from the SMC reported; in one, multiple parents reported; and, in another, both parents and the head teacher reported. In the last case, i.e., the headteachers with parent audits, a designated parent visited the school at least one day a week. The parent decided himself/herself what day to visit.

At the end of each month, a report was sent to the handset associated with a particular school. This report contained a brief message, describing (a) average teacher presence rates in that particular school that month, if any reports had been received, or otherwise a messages saying that no reports had been received; and (b) a comparison number: the average rate of presence reported across all schools in the district.

Some of the head teacher schools and some of the parent-run schools were also chosen to have their monitoring reports backed by financial incentives. In these incentivised schools, teachers would receive a bonus of 30 percent of their monthly salary if they were present on a selected day from all four weeks of the month. To compare monitoring reports with actual outcomes, an independent enumerator was sent to conduct unannounced visits in each of the study schools.

This research design highlights three key questions: How do financial incentives change teacher behaviour when their attendance is being monitored? Who is best placed to monitor teacher attendance? And how can the quality of information provided be safeguarded?

Attendance gains and information distortions

Preliminary results confirm the promise of locally managed systems of accountability. When head teachers are in charge of reporting and financial incentives are attached to these reports, independent spot checks show a statistically significant gain of more than 10 percentage points in teacher attendance. By contrast, effects of non-incentivised schemes and schemes managed by parents alone (because parents on average overstate actual presence more than head teachers) have weaker and statistically insignificant effects.

We also find that both head teacher and parent monitors systematically understate true teacher absenteeism. This is highly relevant when one wants to use this data for administrative and planning purposes at district and ministry levels. In some cases, the under reporting is attributable to how monitors select the days on which to visit the schools. Parents, for instance, tend to visit schools on days when attendance rates are higher—usually at the beginning of the week (Monday) and at the end of the week (Friday). But rewards matter, as monitors are more active when there are financial incentives involved. Interestingly, and perhaps more worryingly, truly absent teachers who are reported as present make up about 10 percent of all reports, irrespective of the identity of the monitor or the financial stakes involved.

“Smart” contracts involving parents to improve cost-effective monitoring

Results from an additional pilot suggest an important role for parents in improving the cost-effectiveness of monitoring. While the day-to-day burden of regular monitoring appears to be a barrier to effective parent-led monitoring schemes, preliminary results suggest that contracts that use multiple monitors—namely both head teachers and parents—can achieve attendance gains similar to the head teacher managed scheme, but at a lower cost.

While head teachers carried the primary burden of monitoring, parents played the role of auditors. Thus, teachers only qualified for bonus payment when parents had verified a head teacher’s report on that that teacher’s presence. The findings indicate that this approach reduces the number of false reports, thereby limiting the payment of bonuses that were not merited.

These results show several promising ways forward for future improvement of local monitoring. They also show the importance of considering the full range of sometimes competing incentives not just for teachers, but for monitors as well. Local stakeholders care about school performance, but have to balance this against time and effort required for effective oversight and dialogue, and against questions of morale and legitimate challenges that face teachers. Localised accountability systems are complex, and we are just beginning to learn how technological advances should be matched with the human challenges facing teachers, managers and parents.

A version of this article first appeared on www.brookings.edu.