What can we learn from the market for skilled workers in Sierra Leone?

Many developing countries focus on education to produce a productive workforce. Human capital models in economics support this. But what we can learn from the Sierra Leonean context is that a push for education and skills development is just one component on the supply side.

Most of the world’s population, and therefore labour force, live in developing countries. Yet labour theories – which have been adapted form developed countries - are not able to explain their markets fully. According to Frolich and Haile (2011), unlike developed countries, labour markets in developing countries have large informal sectors, many small-scale production units, limited social protection coverage, large uninsured risks, seasonality in jobs and workers holding multiple jobs. My recent study of the labour market in Sierra Leone brings to the fore the impact of having a small formal sector; and points to two other key factors: lack of trust in labour market institutions and the role of the development sector.

According to the Sierra Leone labour force survey, the skilled workforce with some level of post-secondary qualification was estimated at just over 50,000 people, or 3% of the labour force (World Bank 2015). Labour force participation is highest for this group, though they also face higher levels of unemployment, and experience underemployment. Current policy to expand access to education and generate decent work should therefore consider why these graduates are not able to find jobs. Is it that labour demand is insufficient? The skills are not the right skills? Labour market institutions prevent firms and working from finding each other and matching?

The data from my study shows that a combination of these factors drive job-lessness and underemployment in Sierra Leone. The data sheds light on the key elements that describe the labour market in terms of demand, supply and institutions.

Labour demand

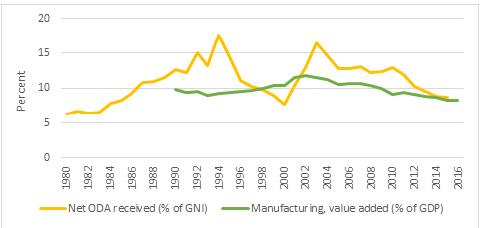

In order for there to be formal jobs, there must be firms and firms must want to hire workers. The size of the formal sector is relatively very small in most developing countries, and in particular, in low-income countries (LIC) like Sierra Leone e.g. in the average LIC, manufacturing contributes just over 8% of GDP, about half the global average of 16% (World Bank 2018). 8% is around the same amount of Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) as a share of gross national income (GNI) that flows to the average LIC, which implies that the aid sector is as important to the economies of developing countries as the manufacturing sector.

Figure 1: ODA vs. the manufacturing sector in LICs (Source: World Bank Data)

A common sentiment by many respondents was “the jobs are not here”, and one reason for this is that the companies are simply not there. Oral histories, sparse archival material, and World Bank data indicate a decline in the manufacturing sector in Sierra Leone since the end of the civil war, which has affected job creation.

Arguably such a situation should spur entrepreneurship and innovation and new firms should be created. Indeed, there has been a rise in entrepreneurship in both Africa and Asia. The entrepreneur is not scarce in Sierra Leone but is reluctant as he/she is faced with lack of access to capital, high interest rates, and high market risks. Instead, graduates long for a paid job with job security - a dominant theme from the focus group discussions I conducted.

Labour supply

The next question is should jobs be created in the formal private sector and public sector, would graduates be able to fill them?

Most employers I interviewed can fill vacancies and are able to train staff to an acceptable level, but routinely complain that the education system imparts theory, but not practical skills. Employers demand more practical skills and spend time and resources training staff on these practical aspects of the job for up to six months after recruitment. The consensus among many respondents was that the education system has failed to update to match market demand, both in terms of introducing new courses and modifying the content of existing courses. According to recruiters, graduates also lack key soft skills like communication skills, analytical skills, and team-working.

Institutional setting

As mentioned above, a common sentiment was that university education was archaic and had not adjusted to meet market demands. Both employers and graduates expressed this, and university students are trapped within an obsolete system. But The problems in the education system start before university at the primary and secondary levels as many students enter university lacking elementary numeracy and literacy skills. A 2013 UN study noted: “Pupils’ outcomes are generally very poor at all levels. Deficiencies are apparent from the early grades of primary and learning outcomes are modest by regional standards”.

A second institutional issue stems from the classic lemons problem in information economics (Akerlof 1970). The signals given by graduates have become blurred to a large extent and employers cannot tell high ability from low ability (Spence 1973). Despite the increasing number of “skilled” workers entering the labour market, systematic issues in the education system may lead to the numbers who are skilled in practical terms by employers’ standards, being a fraction of this entry, with employers not being able to correctly identify who are skilled. This stems from corrupt practices where degrees can be bought, to institutional deficiencies where accreditation bodies do not function effectively creating an environment for unregulated certification and diploma mills.

Finally, trust. My data from focus group discussion indicates clear distrust by workers, and sentiments that recruitment practices are unfair. The common belief is that most jobs are either internally advertised, or circulated within a closed network. To quote one graduate: “These jobs are not for us. Advertising is just a formality”. The perceived exception to this is the aid-industry/development sector which comprise donor organisation, INGOs, and NGOs. Unsurprisingly, the majority – 44% of the 392 graduates surveyed - desire employment in this sector. 38% desire employment in the public sector, 16% in the private sector and 2% wish to be self-employed as a first option. Of the employers interviewed, NGOs and INGOs were more likely to post a new vacancy than the formal private sector or government. This, together with perceptions of fairness, may explain why the majority of university graduated want to work for a donor, NGO or INGO in the development sector.

Conclusions

Many developing countries focus on education to produce a productive workforce. Human capital models in economics support this. But what we can learn from the Sierra Leonean context is that a push for education and skills development is one component on the supply side. Higher spending on education and more graduates only matters if there is quality education and accreditation bodies that can maintain a given standard. For graduates, what matters is employment. A supply-side push needs demand side mobilisation to ensure the private and public sectors are creating sustainable jobs. The development sector provides a buffer for some graduates in Sierra Leone, but these jobs are project-driven and short-term without long-term security. Moreover, if we have jobs being created that are rationed through networks, graduates’ options are limited and at the individual level, the returns to education may actually be lower.

Sierra Leone has recently announced an ambitious policy of free education which is still in the early implementation phase. Now is the time for policymakers to simultaneously think about improving quality and standards, boosting formal job creation, and ensuring a fair labour market for all.