When price is not the whole story: Why rural consumers in Rwanda have low demand for electricity

At first glance, the 7th Sustainable Development Goal seems uncontroversial: “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all.” However, delve into the recent literature on electrification in sub-Saharan Africa and you will discover a growing number of studies that call into question where electrification should fit as a policy priority. In East Africa alone, studies from Kenya, Tanzania, and Rwanda find low rural consumer demand for electricity and mixed impacts of electrification on poverty reduction and economic growth.

What does this research mean for SDG7? Is low demand an indicator that we should prioritise other policy goals, or a sign that low-income countries will require the same type of large investments that the US made to achieve rural electrification? To answer these questions, it is important to better understand consumer demand for electricity.

Exploring demand for electricity in rural Rwanda

I partnered with a private solar company in Rwanda to learn about what shapes consumer demand for electricity. The solar company operates on a “pay as you go” model – customers make a down payment to have a solar home system installed, then pay for days of solar access using mobile money to pay off the solar home system over time. When households have used up all of their solar access days, their system is remotely switched off until they pay for more. Electricity purchases have fixed expiry dates – consumers cannot turn off their system and save days for later.

Around half of consumers in my sample of current solar customers miss at least a few days each month due to non-payment. Of those customers who miss some days, the median customer misses 5-7 days of electricity in a month.

We hypothesised that if demand for electricity was influenced by price, offering incentives for purchasing more electricity would increase the days purchased in a month. We randomly selected customers to receive one of two types of incentives:

- Bulk incentive: buy 4-12 weeks of solar at once, get 1-20 days free.

- Monthly reward: buy 4-12 weeks of solar over the course of a month, get 1-20 days free.

The objective was to observe consumer responses to these incentives as a way to understand how consumers respond to changes in the effective price of electricity.

How much do consumers respond to reductions in the price of electricity?

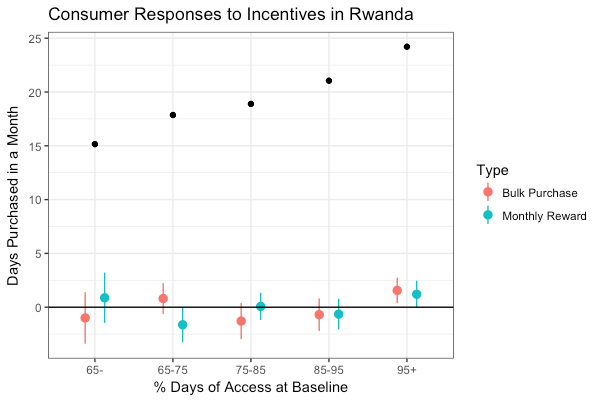

Figure 1 shows that most consumers did not respond to the incentives. Those that did were the consumers who were already paying for solar most of the time.

Figure 1: Black dots represent average monthly purchases for consumers in the control group. Red and blue dots represent changes in purchases among incentivised customers relative to the control group.

Figure 1: Black dots represent average monthly purchases for consumers in the control group. Red and blue dots represent changes in purchases among incentivised customers relative to the control group.

Most studies in sub-Saharan Africa find that consumers are extremely sensitive to price when it comes to electricity, hence the low demand. While at first glance my study finds the opposite, I am focusing on a different aspect of demand: electricity use after a household has already adopted electricity.

Economists usually interpret price insensitivity as a sign that a good is a necessity. For instance, consumers do not reduce gasoline purchases very much when the price rises. If this is true of electricity use, it implies that access to electricity is important for promoting consumer welfare.

Is price the whole story?

Before we conclude that consumers are not sensitive to the price of electricity, it is important to consider alternative explanations for my results. The incentives offered in my experiment do not directly change the price of electricity – they only change the price of electricity if a consumer qualifies for the incentive. Therefore, consumer responses to the incentives may differ from responses to a direct price reduction. I focus on two alternative explanations for my results: consumer uncertainty and the value of liquidity.

Uncertainty matters

Recall that once a consumer buys days of solar, they have to use them right away. Consumers who are not sure how much electricity they will need in the future may not want to purchase enough solar to qualify for the incentive, even if they would purchase more solar as a result of a direct price reduction.

I test for this by comparing consumers with a high variability in the actual quantity of electricity they use (in watt hours) on days when they have purchased solar access to similar consumers with a low variability in actual use. Among consumers who would have to purchase more than a week to qualify for the incentive at the end of a month, those with high variability are less likely to qualify for the incentive than consumers with a low variability. So uncertainty partially explains my results.

Consumers may value liquidity highly

Liquidity is a measure of how easily an asset can be converted into cash. Days of solar cannot be refunded or transferred to someone else, so they are completely illiquid. Like uncertainty, a high value for liquidity could dampen consumer responses to incentives since buying days further in advance reduces consumers’ liquidity.

While I lack a direct measure of the value of liquidity for consumers in my study, I have suggestive evidence that consumers may value liquidity highly:

- The median purchase size for consumers in my sample is 7 days of solar, indicating that most customers make frequent, small purchases.

- 70% of consumers report always visiting a mobile money agent to pay for solar.

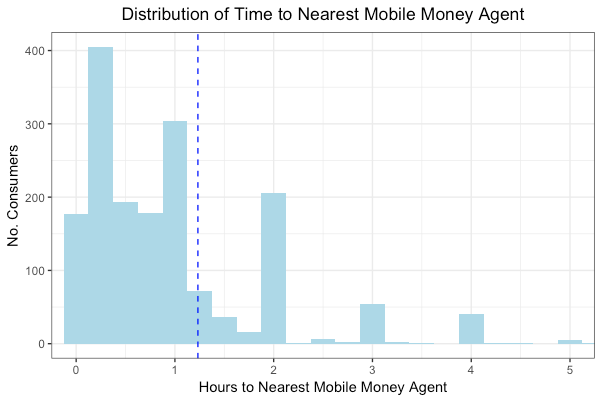

- Figure 2 shows the distribution of the time it takes consumers to reach a mobile money agent. The dotted blue line shows that the average consumer takes well over an hour to reach the nearest agent.

Figure 2

Combining these three facts, we see that consumers routinely incur high transaction costs (travelling to the mobile money agent) to pay for solar even though they could avoid them by making larger, less frequent purchases. This behaviour is consistent with consumers having a high value for liquidity.

Policy implications

While I do not have a definitive answer about how to prioritise SDG7, my study offers a few key takeaways. First, consumers may not be highly price sensitive after adopting electricity. Again, this implies that electrification may enhance consumer welfare more than previous studies would suggest. However, there are a number of non-price factors that shape consumer demand. Accounting for things like transaction costs and high liquidity premiums could enable policymakers to design more effective electrification strategies. Finally, there are likely complementarities between electrification and other policy priorities. In Rwanda, increasing mobile money penetration is a financial inclusion initiative, but my work shows that it could also have implications for consumer demand for electricity.

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of the IGC’s 10 year celebration series. This blog is linked to our work on Energy for all.