World Habitat Day 2017

To mark 2017’s World Habitat Day, the theme of which is Housing Policies: Affordable Homes, we asked researchers working on housing to provide their thoughts on the future of urban housing policy:

Could you give an example of an interesting policy that could help to tackle some of the housing challenges faced in developing cities?

Simon Franklin: large scale low cost housing on the urban periphery

Ethiopia is taking an ambitious approach to delivering formal urban housing at scale. The state provides highly subsidized mortgages for new housing, which is constructed according to centralized urban plans, and subcontracted to local construction firms. All new housing units are in the 4 to 7-storey apartment blocks. Over 200,000 units have already been delivered and in recent years the government has been building over 50,000 houses a year in Addis Ababa alone. The cost of delivering this housing is kept very low by building the houses on less valuable land on the edge of the city and keeping the finish of the houses very basic. This approach requires large complementary investments by owners to make the units live-able. Construction costs per unit come in at between $10,000 and $15,000 per unit.

These new housing projects are risky experiments: up to 60,000 people move at once to sprawling new housing sites, with no existing infrastructure, social capital or local economy. Residents face long commutes to formal jobs in the city centre. It’s possible that these will become dysfunctional areas, cut off from the economic dynamism of the rest of the city.

Yet, there are some promising early signals. Demand for the new housing is high and shows no sign of weakening: preliminary results show a robust rental market, in which prices seem to be increasing as more and more of the units are built and become inhabited. Small businesses, local services and transport connections have moved very quickly into the new neighbourhoods. While the housing is currently on the very periphery of the city, Addis Ababa is predicted to grow rapidly over the coming decades: these newly built suburbs may yet become high density formal residential areas of a much larger city. It remains to be seen whether they will develop into flourishing new neighbourhoods.

Paul Collier: proactive planning for arterial roads and core infrastructure

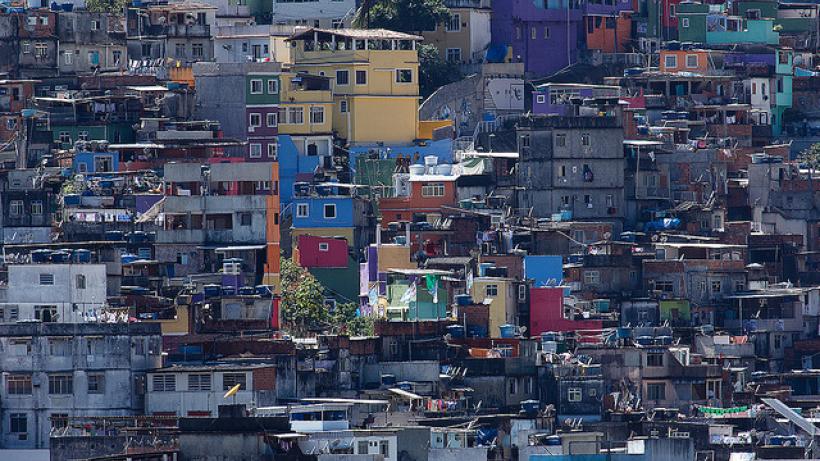

Across the developing world, housing markets have failed to keep pace with rapid urbanization. Consequently, unplanned informal settlements have formed without the infrastructure or clarity of land ownership required for rising productivity and livability. Retrofitting infrastructure after initial settlement has occured is three times more expensive, and almost impossible on a large-scale except through mass slum clearance.

Housing policy therefore needs to become proactive rather than reactive. One proactive housing policy attempted by many cities is to launch ‘large-scale’ public housing programmes. However, the expense of these programmes has too often resulted in housing being built in undesirable far-flung locations, and nowhere near at the scale required to meet demand. A more cost-effective alternative could be to simply provide the core infrastructure required for productive and liveable neighbourhoods before they form. For example, it is relatively cheap for governments to lay out arterial road structures on the rural-urban fringe in advance of settlement, around which private development can occur. The city of New York adopted this approach through the 1811 Commissioners Plan, that demarcated the same road grid system that now carries modern Manhattan’s traffic on it, and water and sewerage infrastructure underneath it. A more comprehensive, albeit higher cost, approach could provide not only arterial roads and core infrastructure, but also basic housing foundations upon which owners can incrementally build. This was the idea behind the World Bank’s sites and services programmes, which were initially criticized but are now being reevaluated as having paved the way for thriving, and often even multi-storied neighbourhoods.

Julia Bird: linking land and housing policy to transport planning

With the current high pace of urban growth seen in many developing countries, the scale of housing construction required can be overwhelming. For example, the population of greater Kampala in Uganda is projected to grow from 3.5 million in 2015 to 10 million in 2040 (World Bank, 2015) – that’s 5,000 new residents to house every single week. No one policy is going to provide these many homes, and so the government needs to work alongside property developers, and current and future urban residents to ensure these housing requirements are fulfilled.

Kampala is investing heavily in transport infrastructure today in anticipation of this urban growth, for example by constructing a new bypass and by planning a Bus Rapid Transit system. These developments are creating potential urban hubs – local centres along the transport routes that act as gateways to the city and to the job opportunities it provides. One key policy for the city to follow today is to ensure that the land around these future hubs is developable into high density residential areas. This will both, create the critical mass of residents necessary to make these transport projects viable, and will ensure that future urban residents live in areas with the best possible access to urban jobs, reaping the benefits of urban life.

Kampala has a complex system of land tenure, with four different types of property rights operating under different rules[1]. Some of these create difficulties in the allocation of land, as the plots are small and frequently subject to dual-ownership claims. This deters developers with the resources to construct multi-story apartment buildings as they need both, strong property rights to ensure the returns to their investments, as well as the possibility to acquire large enough plots of land. While reforming property rights across the whole city is a vast challenge both politically and financially, focusing on areas along current and future transport routes should aide the allocation of land as these areas develop, facilitating development of high-density and good quality housing in accessible areas of the city. Planning for transport and housing together by considering the ease of development and the allocation of land in areas surrounding future transport hubs is crucial in tackling future housing deficits.

Michael Blake: relaxing stringent land use regulations

A low-cost, albeit politically challenging, policy would be to reform the highly stringent land-use restrictions that currently serve to price low-income households out of the formal housing market. One key restriction is on minimum lot sizes for formal sector housing. In Dar es Salaam, the legal minimum size of a housing lot is 375m2 as compared to approximately 30m2 in Philadelphia, US, at similar stages of economic development (Lall et al., 2017). As a result, most urban residents cannot afford to comply with this regulation, frustrating the emergence of a large-scale formal sector housing market to serve this population.

Such stringent land-use regulations are often a legacy of colonial planning laws that are completely removed from the needs of ordinary residents. Although some level of land-use regulation is required from a planning perspective to ensure population density levels are in line with infrastructure provision, regulation needs to be sensible enough not to push large sections of the population into informality. The effects of land-use regulations are far from confined to the developing world. There is a large literature on the role of land-use restrictions in raising prices and limiting supply of housing in developed cities. Katz and Rosen (1987) show that local growth management controls have served to increase house prices in San Francisco by 20-40%. Tackling this barrier to formal housing supply requires strong political will; in the USA, as in the developing world, the rise in formal sector housing prices created by stringent land-use restrictions creates vested interests and political opposition to reform. As such, relaxing land-use restrictions is often opposed by homeowners who benefit from others being priced out the market.

Nina Harari: land sharing in informal settlements

One of the most dramatic manifestations of housing shortages in developing cities is the proliferation of slums. There are a range of policy tools that attempt to tackle this process. At one end of the spectrum, there are market-based approaches such as providing low- and middle-income households with vouchers to be spent on the private housing market. Thailand and Chile are examples of countries in which demand-side subsidies have been successful. The advantage of this approach is that it allows households to choose where to live, minimizing distortions. However, the effectiveness of vouchers is limited if the supply side does not cater to low-income households, either because of regulatory constraints or because this segment is perceived as too risky given the weakness of the rule of law in rental markets. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the government can be directly involved in providing public housing. The disadvantage of this approach is that the provision of public housing is typically very expensive, poorly located, and cannot keep up with the pace of rapidly expanding urban populations. Neighborhood upgrading falls between these two extremes: the government provides basic infrastructure and public goods - such sanitation or paved roads - in slum areas without displacing existing residents. This approach is cheaper and less distortive than public housing, and has the potential to incentivize private investments in a neighborhood. However, it may also make slums more permanent than they would otherwise be, interfering with the process of conversion of informal areas into formal ones.

As such, one interesting area for future policy is ‘land sharing’ agreements on informal settlements, where governments attempt to facilitate a process of formalization by incentivizing the private sector to redevelop slum areas while at the same time promoting the relocation of prior residents on site. This can be achieved by mandating that developers offer part of the units they build in former slum areas to prior residents, at a subsidized rate. This approach attempts to strike a balance between equity and efficiency considerations. However, it typically requires a very strong government to enforce such mandates, and to date there are few examples of successful implementation, such as China.

Mila Friere: flexible and coordinated long run policy

Unfortunately, there is no magic formula that can help developing cities deal with the lack of decent and affordable housing for their residents. The availability of affordable housing depends on structural issues such as land availability, land prices, zoning and regulations and infrastructure. On the demand side, affordability depends on income and purchasing power and the capacity of the local and state governments to help the demand side of the poorest residents. Planning is also crucial. Policymakers may combine affordability and access to labor markets by ensuring that new housing in peri-urban areas is served by affordable transit solutions. They may also use empty land often owned by the municipality, and collaborate with the local communities and leverage their efforts and savings. Successful housing policies based on progressive and community development programs have been implemented in the context of limited public financial resources in countries such as Thailand, India, Bangladesh, and Cambodia.

In all these solutions, it is important to be mindful that housing policies need to take into account many factors beyond construction costs, and that they take time to be designed and implemented. Often these policies will need to be adjusted as the solutions envisaged during preparation do not work because of lack of collaboration and coordination between partners. Successful housing policy in Singapore, for example, took more than 4 decades to accommodate the projected growing population. It was supported by a steady stream of financial resources from the state governments and from the individuals through forced savings or provident funds.

Two great examples of cities/countries that have addressed a lack of affordable housing through a coordinated long-term approach to policy are Hanoi and Chile. Despite its extraordinarily rapid growth, Hanoi has avoided the formation of slums due to sensible planning - it allowed densification of the old cities, pushed connection roads outside the old cities, and avoiding demolishing old houses. This allowed new developers to produce housing in new land and improve the connection between the old cities. Chile was one of the first countries to look at housing as a whole project, combining the supply side and housing developers with the understanding that the purchasing power of the individual families needed to be boosted by targeted subsidies and adequate private finance.

References:

Lall, S. V., Henderson, J. V., and Venables, A. J. (2017), “Africa's Cities: Opening Doors to the World”. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Lawrence Katz & Kenneth Rosen, (1987), “The Interjurisdictional Effects of Growth Controls on Housing Prices” Journal of Law and Economics 30, 149

World Bank. 2015. The growth challenge: Can Ugandan cities get to work?. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.