Information and innovation in the public sector

Bureaucrats frequently make difficult policy choices with limited information. Public service incentives to seek out quality information and schemes to lower the cost of accessing that information could transform decision-making and help support innovations that lead to growth.

-

Brown-et-al-2019-Growth-Brief_Web.pdf

PDF document • 1.23 MB

Introduction

Through its civil service, a capable state raises revenues and provides key public goods and services, using these capabilities to foster economic growth and enhance welfare. To make better-informed decisions related to public policy, the use of information by public officials is crucial.

This Growth Brief seeks to understand the defining characteristics of information use in the public sector and considers potential policy options for navigating the constraints associated with that information use.

Civil service effectiveness is a key driver of economic development (Besley and Persson 2011, Acemoglu and Robinson 2012, Pepinksy et al. 2017). As resources are scarce in developing countries, efficient allocation is vital for providing effective public services. A significant movement towards ‘evidence-based policy’ is founded on the belief that policymakers should hold accurate information to inform their decisions. More informed public officials tend to make better decisions (Callen et al. 2018, Dal Bó et al. 2018, Hjort et al. 2019). However, we have relatively little empirical evidence on what public officials know and how they absorb new information (Rogger and Somani 2018).

In building a better understanding of how information is used, and the incentives that encourage its effective use, recent research in this area offers recommendations that have the potential to transform the quality of policymaking in civil services across the world. In this brief we present the defining characteristics of information use in the public sector and potential policy options for navigating the constraints associated with that information use. We look at recent research that focuses on: (i) how can we ensure better quality information is provided to public sector agents, and, (ii) how can we incentivise good use of this information?

Key messages

- The structure of the public sector hinders the access and sharing of information by bureaucrats.

Governments are typically organised into sectoral monoliths across which there is little incentive to share information. This is partly because much government work is team based, so that civil servants can ‘free ride’ on colleague’s efforts to acquire information. These tendencies are reinforced by cultural norms. - Reducing the cost of acquiring information increases access and use of data.

Opportunities made accessible by information and communication technologies (ICT) and other data-sharing innovations reduce the costs of acquiring and absorbing information. This reduces monopolistic power, the incentive to free ride, and the importance of cultural norms. - The right public service incentives are required for information to be used by policymakers.

The existence of information alone does not necessarily lead to better decision-making. Public service management practices and incentives are crucial determinants of whether public servants acquire, share, and act on good information. - Diagnostic data can nudge public administration towards greater use of evidence.

Reforming the public sector’s institutional environment depends on the pre-existing incentives to acquire and act on information. This creates a potential ‘reform trap’ in which public officials do not have the incentive to empirically identify needed reforms.

Key message 1 – The structure of the public sector hinders the access and sharing of information by bureaucrats

What information currently underlies decision-making by public officials across the world? An IGC-funded study by Rogger and Somani (2018) has shown that bureaucrats in Ethiopia predominantly rely on their ‘tacit’ knowledge – their subjective beliefs over the characteristics of citizens, for operational decision-making. Their findings showed that officials misunderstand the basic conditions of their local jurisdictions with half of public officials making errors that were at least 50% of the true underlying data. As an example, 50% of officials claimed that they served a population at least 50% smaller or 50% larger than it actually was. Tacit knowledge can be a positive input to policymaking, but the potential for errors can lead to significant operational mistakes and misallocation of resources when it is the primary source of information.

IGC research in Zambia (see Box 1) indicates that even when administrative data is available for public officials to base their decision-making on, it is of low quality and under-utilised. It shows that better administrative data would allow scarce human resources to be better targeted across the public service.

Why have many public sectors not therefore developed comprehensive information management systems to inform public officials? They have tried. The World Development Report 2016 presents data that indicates governments across the world have invested more in the intensive use of digital technologies than comparable private sector firms. However, the report notes that these investments have not had corresponding impacts, arguing that “digital technologies have not significantly improved service provider management in government bureaucracies” (World Bank 2016). On-going reliance on tacit knowledge is not a consequence of officials not recognising access to other information sources but is consistent with findings where public officials fail to capitalise on the existing information available (World Bank 2012, 2016; Masaki et al. 2017).

The question is under what conditions will public officials acquire and absorb information for improved policymaking? We highlight three defining characteristics of the economics of information used in the public sector and why these might hinder the absorption of information:

- As natural monopolies, governments face little competitive market pressure to encourage information sharing. Though many public sector activities naturally touch on the mandates of distinct ministries (road safety is both a transport and health issue) information is typically housed within agencies. There are large transaction costs, and weak incentives, to share it. Shared information must pass across agency filing systems and may lead to lower budgets for a particular agency as it becomes clear that some resources should be directed elsewhere.

- An individual official acquires information in the public sector based not only on her own circumstances, but also on the decisions of others (Aghion and Tirole 1997). If another member of your team undertakes the costly effort to learn and organise information for the project you are working on, why should you? Given how much the public sector relies on teamwork, opportunities for such free-riding limits an individual’s incentive to actively access and interrogate data. The distribution of information in public sector hierarchies is therefore determined by the system of incentives for acquiring information and in the interaction of these incentives between managers, subordinates, and colleagues. This leads to a lot of variation in the extent to which officials are informed, and to bottlenecks for the effective transmission of information across the public sector. For example, Best et al. (2017) document ‘islands’ of well-informed procurement officials across the Russian government.

- Cultural norms and structures present challenges around bureaucratic conservatism and the influence of mission-orientated officials. Besley and Ghatak (2005) conceptualise organisations that provide public goods as mission-orientated, providing an impetus for them to recruit mission-motivated employees as this is more likely to improve productivity. However, by definition, such employees are less likely to respond to new information or adopt new practices because they have a pre-defined set of missions or beliefs. This increases the conservatism of the public sector, making policy or organisational change more challenging. As IGC research by Williams and Yecalo-Tecle (2020) in Ghana finds, the overwhelming constraint to bottom-up innovation is hostility to new ideas by senior officials. Viewing the world through a pre-defined set of beliefs can even bias the interpretation of new data (Banuri, Dercon and Gauri, 2017).

Box 1: The impact of poor data on teacher allocation in Zambia

Research in Zambia investigated the impact of payroll mismatch on teacher allocation in schools (Walter 2018). Zambia’s Ministry of General Education stated in its 2015 guidelines that Pupil-Teacher Ratios (PTR) should not be greater than 40 students per teacher, a ratio exceeded by 73% of public primary schools. On the other hand, 21% of schools had more teachers than required to meet the standard. This problem can be resolved by intra-school transfer of teachers. But IGC research found at least 40% of teachers do not work at the location they are paid. This payroll mismatch makes it difficult to identify where teachers are based and deploying new teachers to where they are needed most.

Key message 2 – Reducing the cost of acquiring information increases access and use of data

Recent technological developments and falling ICT costs have greatly increased the information available for bureaucrats, with reduced information acquisition costs contributing to higher uptake. If the costs of acquisition are lower, the constraints created by the public sector’s monopolies, free-riding, and cultural norms are weakened.

The public sector’s experimentation with ICT has been most prominent in the areas of public financial management, with budgets and procurement systems increasingly electronic in the last two decades, improving fiscal efficiency (World Bank 2016). The use of technology has consequently expanded across public administration, demonstrating how information in the public service has fiscal implications.

An IGC pilot study by Callen et al. (2019) in Afghanistan trialled the use of mobile money salary payments and found that this has significant potential to reduce leakages by identifying ghost workers – those who receive a salary but do not work. As compared to cash-based payments, government saw improved transparency, accountability, efficiency, and improved employees’ savings rates with mobile payments. The production of accurate employee information through the programme implied a reduction of the payroll of roughly 7%.

Public officials have also steadily been granted access to ‘information dashboards’ that provide a substantial volume of information at lower costs. In Punjab, Pakistan, an IGC study (Callen et al. 2017) demonstrated how the rapid collection and centralisation of facility-level data, and the communication of that data to relevant government managers, can improve information flows in public bureaucracies. Underperforming health facilities were flagged to senior health officials in real time through an online dashboard. This nearly doubled health facility inspection rates and reduced doctor absences by 20%.

At the same time, many research institutions (including the IGC) have tried to provide public officials with lower cost access to frontier research information in the form of different types of research briefs. Such briefs, similar to policy dashboards, aggregate policy-relevant information and make it salient to officials at low cost. Recent research by Hjort et al. (2019) indicates that this strategy can be effective at overcoming information asymmetries. The researchers investigated whether research findings changed the beliefs of political leaders in Brazilian municipalities. The study found that mayors alter their beliefs as a result of evidence briefings and are more likely to introduce related policies in their constituencies over the next 15-24 months.

Given the public sector often deals with tasks that are context-specific and can’t be fully measured, the tacit knowledge of public officials will always play a substantive role in a nation’s governance. Box 2 provides evidence that innovation can effectively combine ICT and the tacit knowledge of bureaucrats.

Box 2: ICT interventions to improve service delivery

An IGC study in Paraguay highlights the potential power of combining ICT with the tacit knowledge of public officials. Dal Bo et al. (2018) randomised the distribution of cell phones to agricultural extension workers in Paraguay, allowing for regular updates on location, movement, and digitised reporting of activities to be sent to their managers. The ICT intervention improved service delivery. Farmers working with extension workers assigned with phones were 6% more likely to have received a visit. However, part of the experimental design was the use of supervisors’ knowledge of extension agents to determine which agents should get mobile phones. This allowed the researchers to measure the value of supervisors’ pre-existing information. It turns out that this information is valuable, and so interacts with the impact of the ICT intervention. Supervisors selected extension agents who were more likely to be more responsive to the monitoring technology, which had substantive impacts on the effects of the intervention when compared to randomly allocating the mobile phones.

Key message 3 – The right public service incentives are required for information to be used by policymakers

Since information is often not easily or freely available, individual public officials must undertake costly effort to acquire, share, and act on good information. Whether or not they undertake this effort is determined by the incentives under which public officials operate (Aghion and Tirole, 1997). Officials will be disincentivised from investing in acquiring information if they believe their manager has the power to simply over-rule them, or if they believe their manager will not reward them appropriately for their investments. Similarly, officials want their colleagues to undertake the costly investment of acquiring information so long as they benefit from the improved accuracy of their team’s activities.

This is demonstrated by Rogger and Somani (2018). They mimicked a standard Ethiopian government internal communique to provide official administrative data to a randomised set of regional officials. By reducing the marginal information acquisition costs, the researchers identified that the size of the impact of the intervention was determined by the organisation’s management practices. Indeed, some officials did not respond at all to the intervention, whilst others became substantially more informed.

Beyond management practices, the social norms and culture of the public sector often limits the effective use of information in bureaucracies (Fernandez and Moldogaziev 2012). Public official surveys undertaken by the World Bank’s ‘Bureaucracy Lab’ find low scores for staff involvement and the flexibility of the policy process across public service settings (Hasnain et al. 2019). IGC research by Williams and Yecalo-Tecle (2020) in Ghana has shown that a key bottleneck to innovation is managerial resistance to novel ideas that might threaten the existing power equilibrium. They find that there is significant potential for bottom-up innovation to improve work processes, but that harnessing this potential requires changes to managerial practices and organisational processes. Autonomy matched with a culture of empirics can be a powerful combination for public sector performance.

As technology makes information more accessible, the use of this information will depend on officials’ public service incentives – both management practices and cultural norms. The efficacy of information interventions is mediated by the organisational incentives under which officials that are supposed to use them are operating.

Box 3: Electronic procurement for improved governance

Governments spend billions on public procurement and yet processes and procedures often function poorly. In order to reduce costs, electronic procurement (‘e-procurement’) has become a significant focus for policymakers and the subject of a number of pivotal IGC research projects. Research in India, Indonesia, and Pakistan has started to show the benefits and impacts of these systems. Faupel et al. (2016) show that the quality of public works increases after e-procurement is introduced, leading to improved road quality in India and reduced delays in awarding contracts in Indonesia. In Pakistan, research by Bandiera et al. (2017) looks to remove obstacles associated with inefficient procurement by introducing the Punjab Online Procurement System (POPS). The new system and approaches tested under the research have directly decreased the prices being paid by government. Providing another example of how public service incentives mediate the efficacy of ICT reforms, providing more autonomy for procurement officers was an important determinant of these results.

Key message 4 – Diagnostic data can nudge public administration towards greater use of evidence

ICT interventions and associated management systems can have a catalytic impact on public service delivery. They can inform not only public policy decisions but also reform the structure of the public sector. By providing managers with information on their own staff and organisations, they can base their management decisions on more rigorous analytical foundations than solely their experience.

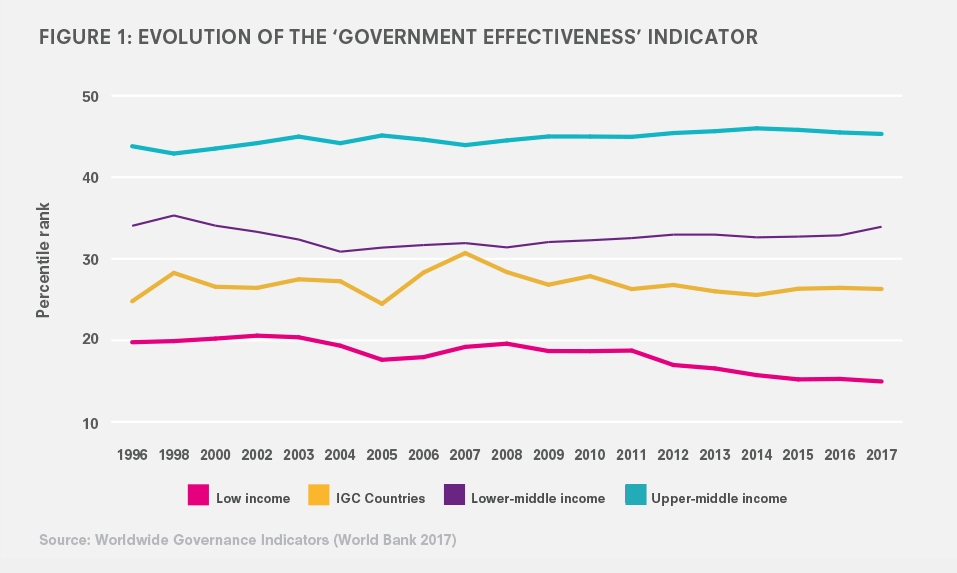

However, while ICT prices have fallen and the availability of technological innovations to improve information flows have increased, corresponding productivity improvements in the public sector have not occurred. Figure 1 shows the evolution of the ‘government effectiveness’ indicator of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (World Bank 2017) indicating stagnant perceptions of government capabilities over the past two decades.

Part of the reason for this stagnation is that information interventions have not always targeted the capabilities of the public administration. For example, although public finance management reforms have often been successful in creating a common budgeting platform in government, they have not always provided information that will help improve the productivity of spending those funds (Hashim and Piatti-Fünfkirchen 2018). Without competitive pressures, reform is often constrained and when is the option to proceed reforms in one setting are often dependent on another (Moore and Hartley 2008). Thus, where reformers have responded to information interventions and improved the public service, they have overcome the incentive to free ride on the efforts of their colleagues, circumvented resistance by their managers, and co-ordinated across disparate agencies.

The large number of constraints to evidence-based reform can lead governments to become stuck in a ‘reform trap’. If managers do not have information on the poor state of information in their agencies, they will not enact reforms to improve the information acquisition capabilities in their organisation.

However, by the same logic the effective use of data on bottlenecks in public administration can improve government institutions and nudge them towards greater use of evidence. This is a rationale for external stakeholders providing diagnostic data on the public administration and its use of evidence. These stakeholders can all play a role in pushing the administration towards an evidence-based approach to public sector reform, with the aim of creating a self-sustaining cycle of demand for and supply of information in government.

Figure 1: Evolution of the ‘government effectiveness’ indicator

Policy recommendations

In this brief, we have outlined findings from new research assessing the use of information across the public sector. Recent evidence has highlighted ways in which the economics of information might differ in hierarchical institutions in the public sector, how information can improve service delivery, and what role external players might have in increasing the state’s use of evidence.

A key area of innovation has resulted from the reduced costs of information associated with technological interventions. However, the most important factor enabling these innovations to have impacts on service delivery are the incentive structures in place for public officials to acquire, absorb, and use that information and analysis for decision-making.

This brief therefore makes a series of policy recommendations stemming from our discussion:

- Investing in ICT innovations can effectively improve flows of information in bureaucracies: Reducing the marginal cost of acquisition makes information easier to access for motivated bureaucrats.

- However, information absorption in the public sector is as much about fixing institutional processes and incentives: Information interventions must be accompanied by appropriate incentives for bureaucrats to acquire information and use it for innovative outcomes.

- For example, monitoring interventions must be accompanied by effective accountability mechanisms: Interventions improving flows of information up the bureaucratic hierarchy must be complemented by measures to ensure information is acted upon.

- Effective use of information is not all about top-down monitoring. Delegating some decision-making authority to individual bureaucrats can often improve performance: Combined with a culture of using data for decision-making, granting greater discretion can be more efficient than current levels of autonomy given to many public official. Delegating authority can increase officials’ incentives to hold information and identify innovative processes. Managers should be rewarded for their staff’s innovation.

- External actors can help nudge public services towards empiricism: Working with public administrations to build first generation data systems on the capabilities of their institutions will generate the incentives for them to become more evidence-based in their decision-making, in a self-reinforcing cycle.

References

Acemoglu, D and J Robinson (2012), Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty, Crown Publishing: New York, NY.

Aghion, P and J Tirole (1997), “Formal and real authority in organisations”, Journal of Political Economy 105 (1): 1–29.

Bandiera, O, M Best, A Khan, A Prat, M Rehman, S Afghan Asad, K Hussain, A Omer Majid and A Jamal (2017), “Motivating bureaucrats: Autonomy vs performance pay for public procurement in Pakistan”, IGC Final Report S-37407-PAK-1.

Bandiera, O, M Best, A Khan and A Prat (2019), “Motivating bureaucrats: Autonomy vs performance pay for public procurement in Pakistan”, IGC Presentation.

Banuri, Sheheryar, S Dercon and V Gauri (2017), “Biased policy professionals”, World Bank Group, Policy Research working paper no WPS 8113.

Besley, T and M Ghatak (2005), “Competition and incentives with motivated agents”, American Economic Review, 95(3): 616–636.

Best, H and D Szakonyi (2017), “Individuals and organisations as sources of state effectiveness, and consequences for policy”, NBER Working Paper 23350.

Callen, M, T Ghani and J Blumestock (2019), “Government mobile salary payments in Afghanistan”, IGC Research Project.

Callen, M, S Ali Hasanain, S Gulzar, Y Khan, (2017), “The political economy of health worker absence”, IGC Working Paper S-6011-PAK-1.

Dal Bo, E, F Finan, N Li, L Schechter (2018), “Government decentralisation under changing state capacity: Experimental evidence from Paraguay” IGC Working Paper and Econometrica forthcoming.

Faupel, Sean, Y Neggers, B Olken and R Pande, (2016), “Can electronic procurement improve infrastructure provision? Evidence from public works in India and Indonesia”, American Economic Journal, 8(3): 258–83.

Fernandez, Se and T Moldogaziev (2012), “Using employee empowerment to encourage innovative behaviour in the public sector’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(1): 155–187.

Hashim, A, M Piatti-Fünfkirchen (2018), “Lessons from reforming financial management information systems: A review of the evidence” (English), Policy Research working paper: WPS 8312, Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Hjort, J, D Moreira, G Rao and J Francisco Santini (2019), “How research affects policy: Experimental evidence from 2,150 Brazilian municipalities”, NBER working paper no. 25941.

Hasnain, Z, D Rogger, D Walker, K Mayo Kay, R Shi (2019), “Innovating bureaucracy for a more capable government”, Washington D.C: World Bank.

Masaki, T, S Custer, A Eskenazi, A Stern, R Latourell (2017), “Decoding data use: How do leaders source data and use it to accelerate development?”, Williamsburg, VA: AidData at the College of William & Mary.

McAfee, A and E Brynjolfsson (2012), ‘’Big data: The management revolution”, Harvard Business Review, 90 (10): 60–68.

Mookherjee, D (2006), “Decentralisation, hierarchies, and incentives: A mechanism design perspective”, Journal of Economic Literature, 44 (2): 367–390.

Mookherjee, D and M Tsumagari (2014), “Mechanism design with communication constraints”, Journal of Political Economy, 122 (5): 1094–1129.

Moore, M and J Hartley (2008), “Innovations in governance”, Public Management Review, 10 (1): 3–20.

Pepinsky, T, J Pierskalla and A Sacks (2017), “Bureaucracy and service delivery”, Annual Review of Political Science, 20(1): 249–268.

Rasul, I and D Rogger (2018), “Management of bureaucrats and public service delivery: Evidence from the Nigerian Civil Service”, The Economic Journal, 128(608): 413–446.

Rasul, I, D Rogger and M Williams (2018), “Management and bureaucratic effectiveness: Evidence from the Ghanaian Civil Service”, IGC Working Paper S-33301-GHA-1.

Rogger, D and R Somani (2018), “Hierarchy and information”, Work Bank Group, Policy Research Working Papers.

Walter, T (2018), “The allocation of teachers across public primary schools in Zambia”, IGC Final Report S-89454-ZMB-1.

Williams, M and L Yecalo-Tecle (2020), “Innovation, voice and hierarchy in the public sector: Evidence from Ghana’s civil service”, Governance, 2019: 1-19.

World Bank (2012), “Better results from public sector institutions”, Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2016), “World development report 2016: Digital dividends”, Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2017), “Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI)”, available at: www.govindicators.org (last accessed: 6 August 2019

Note: Bold text denotes IGC-funded studies.

Citation

Brown, W., Rogger, D., Spencer, E., and Williams, M. (2019). Information and innovation in the public sector. IGC Growth Brief Series 019. London: International Growth Centre.