Filling the gap: How information can help jobseekers

This Growth Brief presents new evidence on interventions that target gaps in labour market information. It finds interventions that certify skills are particularly effective at helping jobseekers secure higher-paying jobs.

-

IGCJ6700-Labour-market-Growth-Brief-190128-WEB.pdf

PDF document • 1.37 MB

Introduction

Interventions that fill gaps in labour market information can help people in developing countries find well-paid jobs. These interventions are much cheaper than common alternative policy options, and initial evidence suggests that firms can also benefit.

In developing countries, jobs are often poorly paid, informal, and unstable, trapping people in poverty and hindering economic growth. Improving the functioning of labour markets is thus a major priority for policymakers. However, a recent review of experimental evaluations of labour market policies in developing countries found that available interventions (training, wage subsidies, job search support) might not be particularly effective (McKenzie 2017). In this Growth Brief, we present new evidence on interventions that target gaps in labour market information.1 We find that interventions that certify skills are particularly effective at helping jobseekers secure higher-paying jobs. Earnings gains range between 10–30%. These interventions are also cheap, and thus highly cost-effective.

Recent cross-country evidence shows that the labour markets of poorer countries are characterised by weak wage growth and a wide use of temporary contracts (Lagakos et al. 2018, Donovan et al. 2018). Informality is also widespread (AfDB 2012).

So how can policymakers in developing countries help jobseekers secure better jobs? In this brief we focus on policies that target information in labour markets. Information is central to efficient market functioning, but in developing countries, crucial labour market information may not be widely available due to the limited diffusion of information technologies, fast urbanisation, and a disproportionately young labour force with little previous work experience. In these labour markets, jobseekers may not be able to easily access information about vacancies, and firms may not be able to accurately assess applicants’ skills. This brief will look at policies designed to address these information frictions.2

Key messages

- Reducing information gaps can increase employment quality and earnings for jobseekers. Recent evidence shows that certifying skills can generate large earnings increases for jobseekers – three recent studies show effects ranging from 10-30%. Employment effects, on the other hand, are more modest, ranging from 2-5 percentage points (pp). Interventions that help jobseekers find information about vacancies, or that target social norms, have also shown impacts on employment outcomes.

- Providing information is cheap and effective. Information interventions cost between $10-20 per participant. This is cheaper and more cost-effective than other active labour market policies such as training or wage subsidies. However, more research is needed on their equilibrium effects.

- Providing information to workers can also benefit firms. Preliminary evidence suggests information interventions can help firms fill vacancies and hire more productive employees. However, firms may underestimate the benefits of investing in information diffusion and quality.

- The way information is provided matters. For firms to learn about jobseekers’ skills, information needs to stand out, and ideally be certified. Further, workers often ignore negative performance feedback.

Key message 1 – Reducing information gaps can increase employment quality and earnings for jobseekers.

Several recent studies found that providing information to jobseekers can significantly improve employment outcomes. We describe these interventions below and present a table of treatment effects estimates in the online appendix.3

ENABLING JOBSEEKERS TO COMMUNICATE THEIR SKILLSET BETTER

Recent experimental evidence shows that programmes that certify existing skills can help jobseekers find better jobs. Certification is particularly relevant for young people, who may have limited formal work experience and credentials. IGC research by Abebe et al. (2018) studies job application workshops which provided skill certificates, and instructions on how to present skills in resumes, cover letters, and at job interviews. Four years later, treated jobseekers had significantly higher earnings (+20%), job satisfaction, and employment duration. Encouragingly, these gains were concentrated among those with the least education and experience. Similarly, in South Africa, helping jobseekers signal test results on cognitive and non-cognitive skills to firms increased their employment rate (+17%) and earnings (+32%) three to four months after treatment (Carranza et al. 2018). In Uganda, providing certificates of soft skills led workers who found employment to earn 11% more in the two years after the intervention (Bassi and Nansamba 2018).

Certificates work best when they focus on general skills. In another IGC-funded intervention in Uganda, vocational training (which was focused on general skills) proved more effective than apprenticeships. The certified skills acquired during the training proved useful up to four years after the intervention. Apprentices, on the other hand, learned firm-specific skills that were harder to certify and were valued less by other firms in the market (Alfonsi et al. 2017).

Reference letters also seem to be a useful and undervalued tool to convey information about skills. In an audit study in South Africa, Abel et al. (2017) encouraged some applicants to seek a reference letter and provided them with a template to do so. They found that including a reference letter with a job application increased employer call-backs by 60%, and doubled them for women. However, in a second experiment, Abel et al. (2017) show that jobseekers underestimate the value of providing reference letters. The same study also develops a standardised template that can be used to help jobseekers obtain reference letters from previous employers.

Jobseekers may also struggle to communicate their preferences. One experiment looked at participants in a large vocational training programme in India. In this context, placement officers had poor knowledge of the jobs trainees wanted to be placed in. Providing the placement officers with this information resulted in more job offers and higher retention rates for trainees (Banerjee and Chiplunkar 2016). Treated individuals were also 1.5-2 pp (8-11%) more likely to be employed three to six months after the intervention.

GIVING JOBSEEKERS INFORMATION ABOUT THE LABOUR MARKET

Jobseekers may find it difficult to gather information about existing vacancies, and to accurately assess their prospects in the labour market. For example, in a developed country context, Spinnewijn (2015) finds that unemployed people overestimate how quickly they will find work, and consequently search too little and deplete their savings too quickly. Similarly, for developing countries, Abebe et al. (2017b) find that jobseekers overestimate the probability of being offered a job when they make an application. Providing information can help: Ahn et al. (2018) find that information about the competitiveness of specific vacancies helps jobseekers target their job applications more effectively.

One reason information may be difficult to obtain is that jobseekers may live far away from firms. This is particularly relevant in the labour markets of the poorest countries, where information technology has limited diffusion, and job search and applications require frequent use of public transport. In rural India, Jensen (2012) informed young women about business process outsourcing (BPO) jobs in the city and offered assistance with the application process. Treated women were 4.6 pp more likely to work in BPO jobs, and 2.4 pp (11%) more likely to work outside the home for pay. In more urban contexts, jobseekers who lack the cash to pay for bus fares to search for vacancies or attend job interviews will experience worse labour market outcomes (Abebe et al. 2017b, Abebe et al. 2018). Using a structural model, Abebe et al. (2017b) estimate that about 30% of the jobseekers who call to inquire about a job in Addis Ababa do not apply for the position because of credit constraints.4

Recent interventions in developed countries show that informing jobseekers can also be done cost-effectively through mass media, with flyer campaigns (Altmann et al. 2018), or leveraging the existing services of employment agencies (Belot et al. 2015).

Job fairs offer an alternative way to bridge the information gaps of jobseekers. In IGC research in Ethiopia, a job fair failed to create much employment, but led low-skill candidates to lower their reservation wages to more realistic levels (Abebe et al. 2017a). In the Philippines, a job fair also allowed attendees to learn about their labour market prospects, leading to a 10.6 pp increase (from 7.7%) in the probability of working in a formal job later (Beam 2016).

SHAPING NORMS

Information can also help to change norms that distort labour market outcomes. A particularly important set of norms are those related to the participation of women in the labour market. For example, in rural India, Bernhardt et al. (2018) found that women’s work outcomes were strongly associated with whether they thought their husbands approved of them working for pay outside the home. Norms become entrenched when people expect to be sanctioned by the community if they do not conform: in the same paper, men’s approval was correlated with whether they expected to be socially sanctioned. However, people may overestimate others’ disapproval: the men thought community disapproval was almost twice as high as it actually was.

Recent research suggests that correcting these false beliefs about the general support for social norms can improve Female Labour Force Participation (FLFP). In Saudi Arabia, where husbands can typically decide whether their wives can work, the vast majority of young married men in an experiment privately supported FLFP, but also underestimated support from similar men. Informing them of the true level of support increased sign-up for a job-matching service for their wives, and four months later, the wives were more likely to have applied and interviewed for a job outside of home (Bursztyn et al. 2018). Women’s beliefs also matter. In rural Uttar Pradesh, India, McKelway (2018) finds that improving women’s belief in their own ability to attain desired outcomes raises subsequent work for income by 36% (8 pp) after four months, possibly because women were inspired to exert more effort to find employment.

Norms become entrenched when people expect to be sanctioned by the community if they do not conform.

Other norms that are relevant in the labour market are related to the prestige of various occupations. Groh et al. (2015) in Jordan offered a job-matching service to firms and recent graduates. However, youth rejected 28% of interviews they were offered. Those youth who took a job left within a month 83% of the time. Survey evidence suggests that this was because the jobseekers perceived the jobs on offer to have low prestige. So far, there has been no work that tries to identify whether norms related to prestige are malleable.

NOT ALL INTERVENTIONS WORK, OR WORK FOR LONG

Timeframes matter, and not all interventions have long-lasting impacts. For example, Dammert et al. (2015) used SMS messages to provide information on job vacancies. Just giving access to a public dataset had no impact, and while adding other sources of information (e.g. newspaper ads) did increase employment, effects did not persist for more than three months. Further, Abebe et al. (2018) find that the formal employment effects of transport subsidies documented eight months after treatment do not persist in the four year follow up. Piloting and experimentation is thus crucial to determine whether a specific policy will work in a given context.

Key message 2 – Providing information is cheap and effective.

In this section, we look at the effects and costs of various labour market interventions. We compare the information interventions described above to other classic interventions, such as skills training and cash transfers. The latter are also popular policy options (Blattman & Ralston 2015).

McKenzie’s comprehensive literature review (2017) looks at both employment outcomes and earnings, which we summarise in the online appendix.5 Here we present a summary of the costs of the interventions and their impacts on earnings.

COST

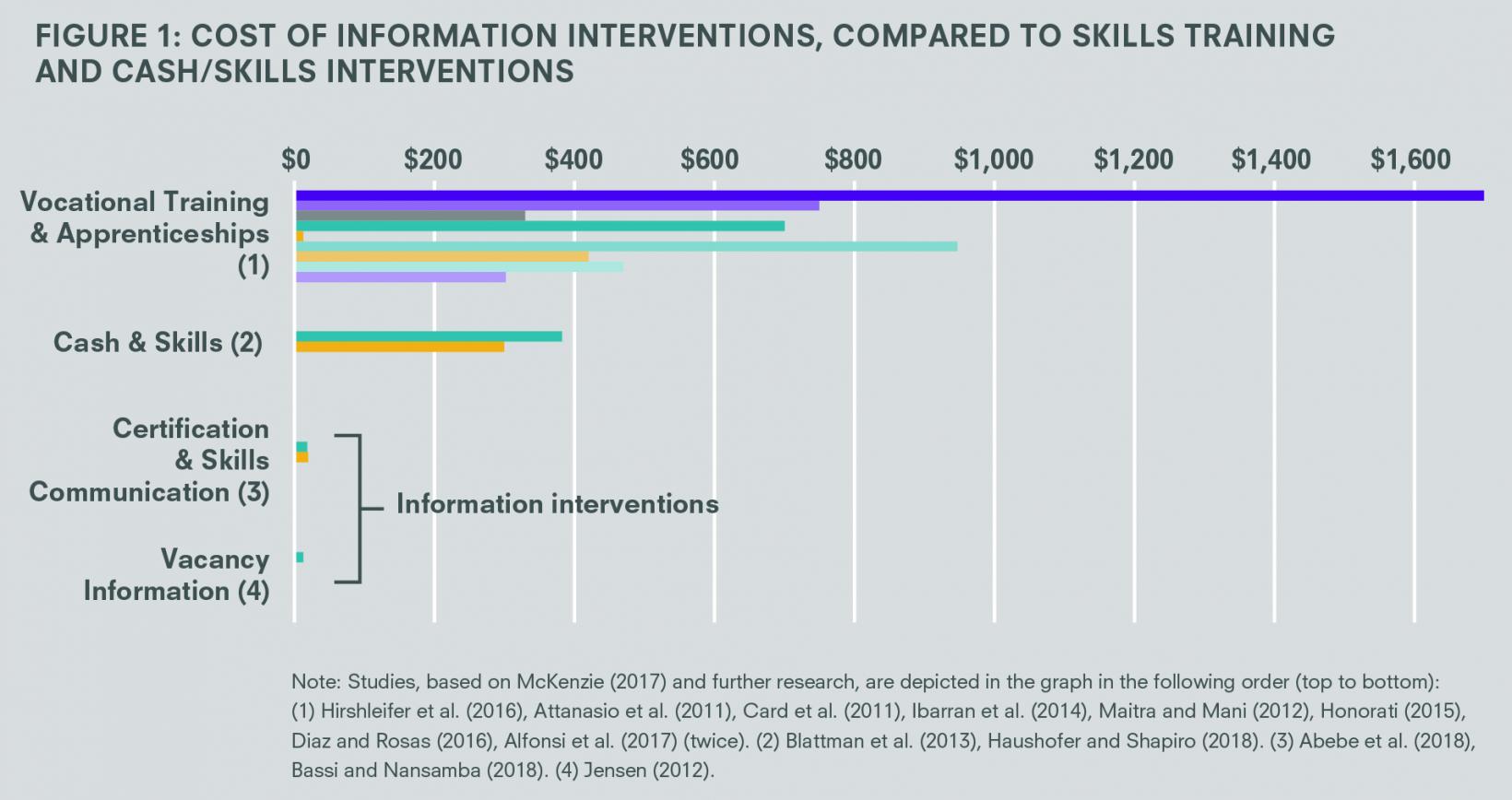

Information interventions tend to cost about $20 per participant. They are thus much cheaper than vocational training and cash/skill transfers, which often cost several hundred dollars per participant. We present a summary of the cost of various types of interventions in Figure 1.

COST-EFFECTIVENESS

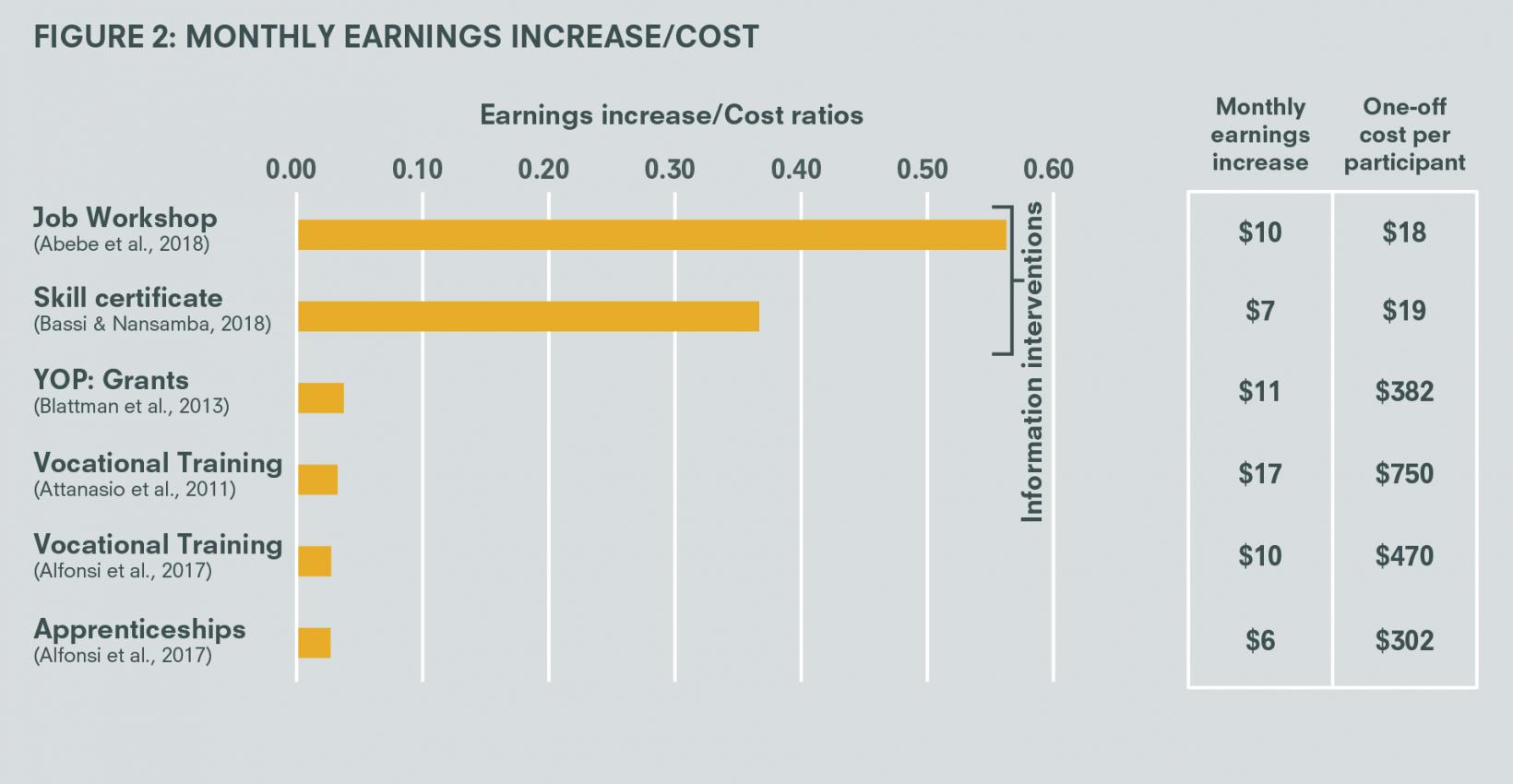

Information intervention can have large impacts for a small financial investment. For example, the job application workshop of Abebe et al. (2018) generated monthly earning gains of $10 per participant for a one-off investment of $18.20, after four years. Similarly, Bassi and Nansamba (2018) costs $19.10 and generated gains of $7 per month if the participant was employed. If we use the ratio of earning gains over costs, a simple measure of cost-effectiveness, we find that information interventions are among the most cost-effective policy options in labour markets (Figure 2)6.

An important caveat is that we have little direct evidence on the effects of these interventions on other jobseekers. The cost-benefit case would be weaker if these interventions caused displacement of other jobseekers.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Key message 3 – Providing information to workers can also benefit firms.

Firms can also benefit from interventions that provide information to workers, through two distinct channels. First, skills certification enables them to screen job candidates more effectively, raising quality. Second, interventions that inform jobseekers about existing vacancies can reduce labour shortages or help firms attract the right workers.

- Screening workers: Enabling jobseekers to communicate their skills better helps firms pick better candidates. This is supported by the earnings gains reported in Figure 2: if employees are being paid more, this suggests the matches are of better quality. For example, Bassi and Nansamba (2018) show that providing certificates of soft skills in Uganda led workers who found employment to earn 11% more in the two years after the intervention. Abebe et al. (2018), also document an increase in earnings conditional on employment.7 Further they show that treated workers stayed in the same job for longer, and that they report their skills to be better matched to their job.

- Attracting workers: Small firms in developing countries face search costs (Hardy and Casland 2015), which can lead to unfilled vacancies or to a mismatched pool of applicants. Informing jobseekers about vacancies is likely to alleviate this – just as advertising more vacancies leads to more hiring, particularly in slack labour markets (Behaghel et al. 2014). Information about the nature of the vacancies (e.g. the wages paid and how wages grow with tenure) is also likely to help employers attract the right candidates for the position (Ashraf et al. 2018, Deserranno forthcoming).

If firms can benefit from these jobseeker interventions, why do they not provide the same services themselves? Recent evidence suggests that this may be because firms may underestimate the value of specific interventions. For example, IGC research by Abebe et al. (2017b) shows that offering small monetary incentives to applicants improves the standard of applicants, but that local recruiters underestimate the positive impacts of this intervention. In fact, firm managers expect the incentive to decrease applicant quality.

Key message 4 – The way information is provided matters.

There are some key elements to pay attention to when designing an information intervention.

- Making information stand out: Information has to be provided in a way that captures people’s attention. Faced with complex problems and limited attention spans, people often ignore valuable information, and benefit from summaries highlighting key relationships (Hanna et al. 2013). Information interventions may thus fail to improve outcomes if the information they provide is not absorbed by programme participants.

- Certification is useful: Information is not always trusted. For example, in a recent trial in South Africa, providing jobseekers with certified skills assessments substantially improved employment and earnings, while giving jobseekers the same information without a formal certificate did not 8(Carranza et al. 2018). This suggests that even if jobseekers are aware of their skills, they may not be able to credibly signal these skills to potential employers.

- People might ignore the new information if it threatens their self-esteem: There is growing evidence that people interpret information in ways that help them maintain a positive image of themselves. For example, Mobius et al. (2011) use performance on an IQ test to show that people will change their self-assessment too much when told they likely did well, and too little when told they likely did not do well. The same subjects do much better at this “belief updating” when their self-esteem is not at stake. In a labour market context, providing information about one’s skills or job prospects is likely to generate a similar type of behaviour. Hence information provision is likely to work better if it is framed in terms of “good news” that does not threaten jobseekers’ self-image. Affirming the jobseekers’ self-worth (such as giving them positive information on other skills) can also help accurate processing (Cohen et al. 2000).

A woman looks at a poster advertising jobs on the street, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. (Photo by In Pictures Ltd./Corbis via Getty Images)

Policy recommendations

In this brief, we have summarised recent experimental evidence on improving information in labour markets. Recent evidence has shown that classic labour market interventions are less effective than assumed (McKenzie 2017) and are moreover relatively expensive (hundreds of dollars per participant). Information interventions, on the other hand, can generate large earnings gains for workers at a low cost, and can benefit firms as well.

The options for a government wanting to increase earnings or employment quality through information interventions are:

- Skill certification and workshops to help jobseekers communicate their skillset better: simply certifying existing skills improves jobseeker earnings.

- Encouraging applicants to provide reference letters: applicants may not think to do this, but it improves call-backs, particularly for women.

- Mass media to spread information about vacancies to remote populations: this may be the cheapest way to do this; similar interventions have had tangible impacts on employment.

- Job fairs to help firms and jobseekers form more realistic expectations, improving matches: while job fairs themselves do not seem to generate much additional employment, they help improve labour market functioning, such as by lowering reservation wages (above which jobseekers will accept a job offer).

- Financial interventions (such as application incentives or transport subsidies) can also help jobseekers search and apply for vacancies in settings where labour market information is costly to access.

Policymakers should be clear about the goals they want to achieve. While few information interventions so far have shown large impacts on employment itself, they are likely to improve earnings and the quality of the employment.

References

Abebe, G, S Caria, M Fafchamps*, P Falco, S Franklin, S Quinn* and F Shilpi (2017a), “Job fairs: Matching firms and workers in a field experiment in Ethiopia”, The World Bank.

Abebe, G, S Caria and E Ortiz-Ospina (2017b), “The selection of talent”, Working Paper.

Abebe, G, S Caria, M Fafchamps*, P Falco, S Franklin and S Quinn* (2018) “DP13136 anonymity or distance? Job search and labour market exclusion in a growing African city”, London, CEPR.

Abel, M, R Burger and P Piraino (2017), “The value of reference letters-experimental evidence from South Africa”, Harvard University. Processed.

Abel, M, R Burger, E Carranza and P Piraino (2018), “Bridging the intention-behaviour gap? The effect of plan-making prompts on job search and employment”, The World Bank.

AfDB (2012), “African economic outlook 2012: Promoting youth employment”, OECD Publishing.

Ahn, SJ, B Feigenberg and R Dizon-Ross (2018), “Improving job matching among youth”, Columbia University.

Alfonsi, L, O Bandiera*, V Bassi, R Burgess*, I Rasul*, M Sulaiman and A Vitali (2017), “Tackling youth unemployment: Evidence from a labour market experiment in Uganda”, STICERD-Development Economics Papers.

Altmann, S, A Falk, S Jäger and F Zimmermann (2018), “Learning about job search: A field experiment with job seekers in Germany”, Journal of Public Economics, 164: 33-49.

Ashraf*, N, O Bandiera* and S Lee (2018), “Losing prosociality in the quest for talent? Sorting, selection, and productivity in the delivery of public services”, No. 88175. London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE Library.

Attanasio, O, A Kugler and C Meghir (2011), “Subsidising vocational training for disadvantaged youth in Colombia: Evidence from a randomised trial”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3: 188-220.

Bandiera*, O, R Burgess*, N Das, S Gulesci, I Rasul* and M Sulaiman (2013), “Can basic entrepreneurship transform the economic lives of the poor?”, LSE.

Banerjee, A and G Chiplunkar (2016), “How important are matching frictions in the labour market? Experimental & non-experimental evidence from one Indian firm”.

Bassi, V, A Nansamba and B. R. A. C. Liberia (2018), ” Screening and Signaling Non-Cognitive Skills: Experimental Evidence from Uganda”, University College London.

Beam, E (2016), “Do job fairs matter? Experimental evidence on the impact of job-fair attendance.” Journal of Development Economics, 120: 32-40.

Behaghel, L, B Crépon* and M Gurgand (2014), “Private and public provision of counselling to job seekers: Evidence from a large controlled experiment”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(4): 142-74.

Belot, M, P Kircher and P Muller (2015), “Providing advice to job seekers at low cost: An experimental study on on-line advice”.

Bernhardt, A, E Field*, R Pande*, N Rigol, S Schaner and C Troyer-Moore (2018), “Male social status and women’s work”, In AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108: 363-67.

Blattman*, C and L Ralston (2015), “Generating employment in poor and fragile states: Evidence from labour market and entrepreneurship programmes”, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2622220 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2622220

Bursztyn, L, A González and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2018), “Misperceived social norms: Female labour force participation in Saudi Arabia”, No. w24736, NBER.

Carranza, E, R Garlick, K Orkin and N Rankin (2018), “Job search, hiring, and matching with two-sided limited information about workseekers’ skills”.

Cohen, G. L., Aronson, J., & Steele, C. M. (2000). “When beliefs yield to evidence: Reducing biased evaluation by affirming the self.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(9), 1151-1164.

Dammert, A, J Galdo and V Galdo (2015), “Integrating mobile phone technologies into labour market intermediation: A multi-treatment experimental design”, IZA Journal of Labour & Development, 4(1): 11.

Deserranno*, E (forthcoming), “Financial incentives as signals: Experimental evidence from the recruitment of health workers”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Donovan, K, J Lu and T Schoellman (2018), “Labour market flows and development”, In 2018 Meeting Papers, no. 976. Society for Economic Dynamics.

Groh, M, D McKenzie*, N Shammout and T Vishwanath (2015), “Testing the importance of search frictions and matching through a randomised experiment in Jordan”, IZA Journal of Labour Economics 4(1): 7.

Hanna*, R, S Mullainathan and J Schwartzstein (2013), “Learning through noticing: Theory and evidence from a field experiment”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(3): 1311-1353.

Hardy, M and J McCasland (2015), “Are small firms labour constrained? Experimental evidence from Ghana”, Unpublished.

Jensen, R (2012), “Do labour market opportunities affect young women’s work and family decisions? Experimental evidence from India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(2): 753-792.

Lagakos*, D, B Moll, T Porzio, N Qian and T Schoellman (2018), “Life cycle wage growth across countries”, Journal of Political Economy 126(2): 797-849.

McKelway, M (2018), “Women’s self-efficacy and women’s employment: Experimental evidence from India”, MIT.

McKenzie*, D (2017), “How effective are active labour market policies in developing countries? A critical review of recent evidence”, The World Bank Research Observer, 32(2): 127-154.

Mobius, M, M Niederle, P Niehaus and T Rosenblat (2011), “Managing self-confidence: Theory and experimental evidence”, No. w17014, NBER.

Spinnewijn, J (2015), “Unemployed but optimistic: Optimal insurance design with biased beliefs.” Journal of the European Economic Association, 13(1): 130-167.

Note: Bolded text denotes IGC-funded/sponsored projects.

*Denotes IGC research leadership or affiliates.

Citation

Caria, S., & Lessing, T. (2019). Filling the gap: How information can help jobseekers. IGC Growth Brief Series 016. London: International Growth Centre.

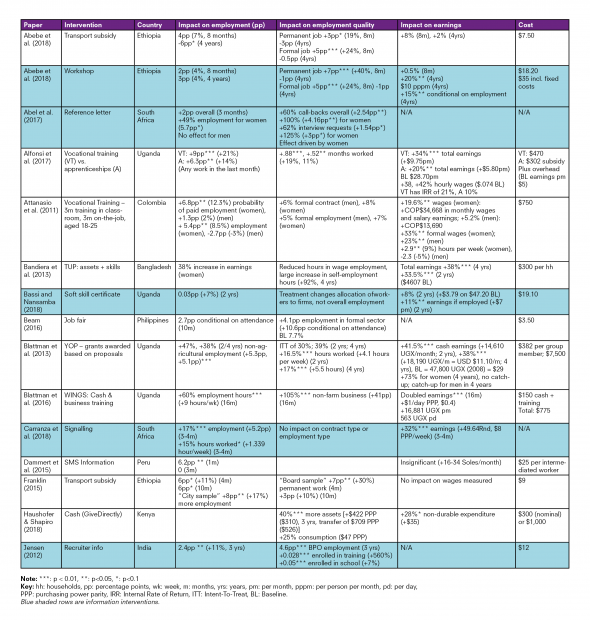

Appendix

Table: Job interventions and their impact on employment outcomes and earnings

*This table summarises McKenzie’s comprehensive literature review (2017).

The following references appear in the table above, but not in this brief’s references section:

Bandiera, O, R Burgess, N Das, S Gulesci, I Rasul and M Sulaiman (2013), “Can basic entrepreneurship transform the economic lives of the poor?”, LSE.

Blattman, C, E Green, J Jamison, M Lehmann and J Annan (2016), “The returns to microenterprise support among the ultrapoor: A field experiment in postwar Uganda”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 8(2): 35-64.

Franklin, S (2015), “Location, search costs and youth unemployment: A randomised trial of transport subsidies in Ethiopia”, Centre for the Study of African Economies Working Paper WPS/2015-11.

Haushofer, J and J Shapiro (2018), “The long-term impact of unconditional cash transfers: Experimental evidence from Kenya”, Busara Center for Behavioural Economics, Nairobi, Kenya.