Growth brief: Harnessing FDI for job creation and industrialisation in Africa

During the last decade and a half, African economies grew at nearly double the rate of the 1990s. However, the commodity boom obscured a key weakness in African economic performance – slow manufacturing growth.

-

GrowthBrief_FDI-in-Africa-FINAL_WEB.pdf

PDF document • 477.43 KB

Introduction

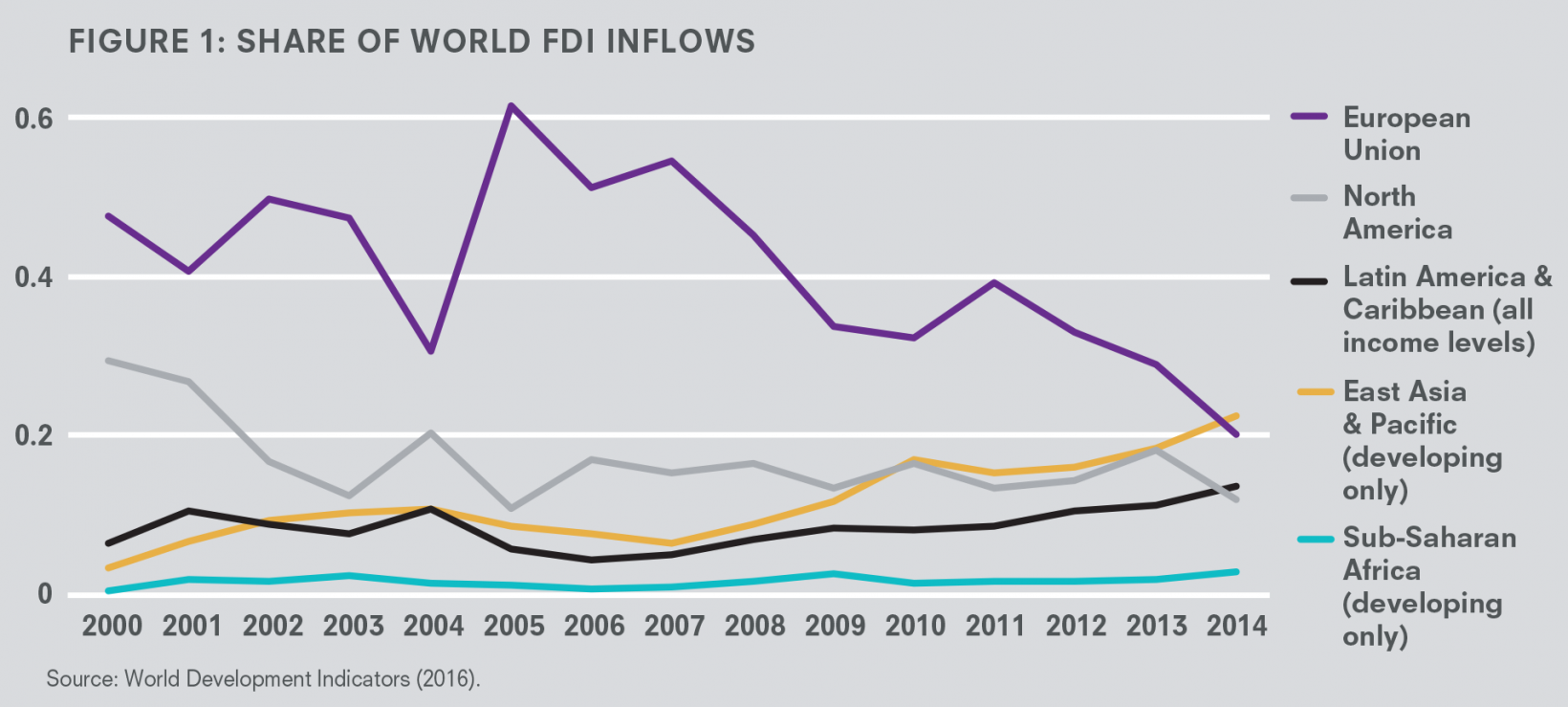

Productivity increases in Africa, after 2000, happened without the deep structural change that shifts labour from low to high productivity jobs (McMillan et al., 2014). Moreover, the recent wave of trade globalisation and FDI in manufacturing has largely passed Africa by. In a period when most developing countries’ shares of global manufactured exports have more than doubled, Africa’s has stagnated in the low single digits.

Rather than being a leading sector, manufacturing in Africa has been lagging. This has contributed to stagnation in growth potential and job creation in high value-added sectors, hampering economic growth (Ansu et al., 2016).

Increasing FDI can enable Africa to raise productivity and expand high value-added activities. Recent studies show that FDI can generate productivity spillovers, which in turn could create decent jobs and a sustained impact on growth and development in Africa. Making it easier and more attractive for foreign firms to invest in African manufacturing and high-value added services should therefore be a priority for governments and international donors.

The growing importance of global value chains and trade in “tasks” (intermediate goods and services) create new opportunities for FDI in Africa. To exploit these opportunities and attract FDI, the main constraints that need to be addressed are the poor quality of institutions, inadequate infrastructure, and policy-distorting price incentives. These actions must be accompanied by policies to increase FDI spillovers and backward linkages to support structural transformation and growth.

Key messages

-

FDI can catalyse industrialisation and structural transformation, creating new jobs in Africa.

By increasing firm capabilities and generating important productivity spillovers, through technology and know-how transfers, FDI can help engineer a structural shift to higher productivity jobs and high-value added industry niches.

-

Infrastructure, institutions, and incentives must be addressed to attract more FDI.

Improved infrastructure, especially in power and transport; stronger institutions, from border controls to investment promotion agencies; and reductions in price-distorting trade policies are needed to attract FDI.

-

Policies to promote FDI must also seek to get more out of FDI.

The broader benefits of FDI are not automatic. Policies to facilitate spillovers and backward linkages are crucial to ensuring that FDI contributes to structural transformation and growth.

Key message 1 – FDI can catalyse industrialisation and structural transformation, creating new jobs in Africa

By combining long term investment with control, FDI can facilitate the transfer of capability (technology and management know-how), and provide access to regional and global value chains (Prasad et al., 2003). FDI can thus generate productivity gains not only in the firm itself but in the industry as a whole. By increasing within-sector competition, FDI forces domestic firms to increase efficiency and drives out the least efficient firms, thereby improving overall productivity. Second, the technology and know-how of the foreign company can be transferred to domestic firms in the same sector (horizontal spillover) or along the supply chain (vertical spillovers) through the movement of people and goods. Increased productivity leads, in turn, to more decent jobs and a structural shift towards higher value-added activities (Farole & Winkler, 2014).

In the aftermath of the commodity boom, with many countries in Africa stuck with low productivity jobs and a lagging manufacturing sector, FDI can catalyse the structural transformation needed to underpin growth going forward (Sutton & Kellow, 2010). Investment-based strategies that encourage adoption and imitation, rather than innovation, are particularly important for policy approaches in countries at earlier stages of development (Acemoglu, et al., 2006). The East Asian experience over the last three decades has shown how, in a globalising world, FDI can help upgrade and diversify industrial structures of host countries (Chen et al., 2015).

Three observations illustrate the potentially transformative role of FDI in Africa. First, around half the biggest export companies operating in African countries that have successfully gone from low to high industrialisation began as FDI ventures. Second, in the African countries that currently show the greatest prospects for industrialisation, around one fourth of their leading industrial companies are companies of foreign origin. Third, in sub-Saharan African economies as in East Asia, FDI has broadened the scale of activity across existing industries and the range of industrial activities (Sutton & Zhang, in progress).

With the rise of global value chains, Africa has an unprecedented opportunity to attract investment in higher value-added, export-led manufacturing. This has shifted the focus from achieving comparative advantage along the whole production chain in favour of advantages in specific niches (UNECA, 2013). Segmented value chains create opportunities for developing countries to specialise, with FDI productivity spillovers helping them move progressively into higher value-added tasks, over time.

Figure 1: Share of world FDI flows

Key message 2 – Infrastructure, institutions, and incentives must be addressed to attract more FDI Infrastructure

Reliable electricity and efficient transport systems can attract FDI

Although Africa’s infrastructure is improving, it is starting from a low base. Lack of efficient basic infrastructure such as electricity, transportation, ICT and water is a major cause of Africa’s low levels of competitiveness and productivity, along with low numbers of exporters and limited intra-regional trade (African Economic Outlook, 2014).

Electric power remains Africa’s single greatest infrastructure constraint, with low access, poor reliability and high cost as key issues. According to a recent World Bank Enterprise Survey (2011/2013), 37% of foreign manufacturing firms identified electricity as a major constraint for doing business in Africa (Chen et al., 2015). Reliability of electricity supply is a major problem. African manufacturing enterprises experience power outages 56 days per year, on average, resulting in a loss amounting to 6% of annual sales (ibid). The average effective electricity tariff in sub-Saharan Africa is high, around USD 0.13 per kWh compared to USD 0.04–0.08 per kWh in other developing countries. Transport infrastructure runs a close second in terms of constraints to FDI, especially for the onethird of African countries that are landlocked. Poor infrastructure raises the cost of inputs to manufacturing and other activities. In Rwanda, for example, transport costs from coastal ports to Kigali add roughly 50% to the cost of landed inputs.

FDI and the service sector

Efficient services are critical to economic development as inputs into the production of other services and goods. For example, a competitive financial sector is essential to mobilising domestic savings and channelling them into productive activities. Business services such as accounting and legal services reduce transaction costs associated with the operation of financial markets and the enforcement of contracts. Lastly, retail and wholesale distribution services are a vital link between producers and consumers. The rise of global value chains and trade liberalisation in Africa has further increased the importance of services in the value addition that takes place at each step along the supply chain.

FDI is a particularly important channel for international provision of services and associated transfer of knowledge and know-how, as well as a mechanism through which higher quality, lower cost services improve total factor productivity of firms that use services relatively more intensively. Telecommunication services, for example, have been shown to be vital to export growth and effective participation in supply chains. An implication is that services trade liberalisation can have positive effects because foreign services are a channel for knowledge and technology transfer. In a paper for the IGC, Hoekman and Sherpherd (2015) found that increases in services productivity were associated with increases in manufacturing productivity and, ultimately, export growth. Promoting efficient services therefore becomes crucial in harnessing the benefits from FDI and advancing industrialisation.

Equally important for attracting FDI is addressing the policies governing infrastructure. For example, restrictions on competition through cabotage1policies, axle standards, and differing weight standards as well as licensing or border inspections all work to undermine the efficiency of road infrastructure, and increase the pressure on other forms of connectivity, such as telecommunication and air transport (see Arvis, et al., 2014). Reducing delays at the border and in transit can have a dramatic effect on reducing costs – and therefore increasing exports (ibid). On average, in 2006, it took 116 days to move an export container from the factory in Bangui, Central African Republic, to the nearest port and fulfil all the customs, administrative, and port requirements to load the cargo onto a ship (OECD, 2011). Even though the number of days has been falling in Africa, exporters and importers require 50% more time to market exports than in East Asia.2 Another issue is delays at ports and airports where, for example, closed sky arrangements can reduce the efficiency of airport facilities (Moran 2001; Chen et al., 2015).

Image credit: Ben Welle

Institutions

Strengthening institutions like investment agencies and customs authorities are key to incentivising FDI

Too often, weak institutions stifle investment in Africa. Trade barriers include poorly performing customs services, inadequate coordination of agencies operating administration at border posts, and standards agencies that lack mutual recognition agreements with neighbours and major supplying countries. Strengthening customs authorities and establishing export promotion agencies can significantly facilitate trade and attract further FDI (Lederman et al., 2009). Moreover, well-designed and managed investment promotion agencies represent a cost-efficient way of attracting FDI – from existing as well as new foreign investors – by reducing information costs and streamlining approvals (see the IGC Enterprise Maps and related research by Sutton & Kellow, 2010).3

Lastly, underperforming educational institutions that do not generate enough high skilled workers, coupled with rigid labour markets, can deter FDI. By 2040, Africa is expected to have the world’s largest labour force, but the challenge will be to have a high enough share of skilled workers in the labour force.

Education levels remain relatively low, with sub-Saharan Africa only achieving a secondary school enrolment rate of 40%, and there is a large mismatch in skills that job seekers offer and those sought by employers (ibid). Reforms are needed to the curricula of secondary and tertiary institutions. Technical and vocational training programmes could be one way to equip African workers with the skills that businesses need (see for example IGC research by Casey et al., 2011; Martins et al., in progress; and Kingombe, 2012). Finally, employers and employees need more flexible employment rules, as labour laws in many African countries are restrictive in comparison with other regions.

Knockout factors

A pre-requisite for stimulating investment in productive activities is a reasonably robust investment climate – peace and security, macroeconomic stability, respect for property rights, and manageable levels of corruption. These “knockout factors” are so critical to a firm’s operations that their absence undermines domestic and foreign investment, especially in manufacturing. Resource-seeking FDI is generally more tolerant of a poor investment climate because the costs of enclave investments are less dependent on the broader economic and political conditions and bespoke arrangements can be agreed with local elites. For efficiency- or market-seeking FDI, however, political or economic instability may be an insurmountable obstacle to investment. The presence of corruption in government is debilitating and can effectively stifle FDI inflows, even when other aspects of the investment climate are favourable. These conditions are often deep-rooted institutional failures, politically sensitive and difficult for donor agencies to address, yet they are fundamental in attracting FDI and need immediate attention.

Incentives

Reducing policy-induced price distortions is essential to boosting exports and FDI

Policy-distorted price incentives that discourage exports also deter FDI.4 The worst culprit is overvalued exchange rates, which numerous studies have found to deter exports of manufacturing and undermine growth (Rodrik, 2008). This is less of a problem in Africa than it was two decades ago, and the introduction of floating exchange rates and inflation targeting has improved matters. But maintaining a competitive real exchange rate is crucial if Africa is to expand manufacturing exports.

While tariffs and trade restrictions in Africa have been reduced, they continue to act as disincentives to exports and FDI, and distort domestic investment, by reducing the competitiveness of manufacturing (Looi Kee et al., 2009). The rise in global value chains has increased the opportunity cost of maintaining inefficient border procedures, high tariffs, non-tariff barriers, and restrictions on the flow of information and people. As every day of delay in the movement of goods in the value chain raises the price to the final consumer, importing has to be as efficient as exporting. The need to coordinate delivery times and multiple inputs into production at a given stage mean that a wide variety of both public and private services are critical to global connectedness. Regional trade agreements that drive down trade costs while expanding markets can have a powerful effect in attracting FDI.

Experience in China and elsewhere in Asia shows that special economic zones (SEZs) can be highly effective in attracting FDI, by ensuring that the infrastructure, institutions and incentives all work to support manufacturing and facilitate trade. But with few exceptions, African SEZs have underperformed. Farole (2011) suggests that the key success factors are infrastructure and trade facilitation.

The case for price incentives or subsidies appears to be weak. In his review of African experience, Farole (2011) concludes that incentives and subsidies are not a significant factor in the success of SEZ’s. More generally, effective subsidies take many forms and can be paid for by the consumer directly (e.g., tariffs) or by government (e.g., tax incentives, reserve procurement policies, state-owned enterprise pricing, preferential loans). Harrison and Rodríguez-Clare (2010) find little evidence that countries benefit from price incentives (e.g., to deal with externalities or knowledge spillovers from FDI).

Key message 3 – Policies to promote FDI must also seek to get more out of FDI

Attracting FDI does not guarantee economic development. The benefits of FDI and its productivity spillovers depend on the macroeconomic and structural conditions of the host economy (UNCTAD, 2015). Laissez faire policies can hinder the benefits of FDI, leaving economies vulnerable to restrictive business practices, oligopolistic pricing, or transfer pricing to avoid taxes. FDI can be directly harmful when poorly managed, for example, as a result of a deterioration in the balance of payments as profits are repatriated (Lederman et al., 2010).

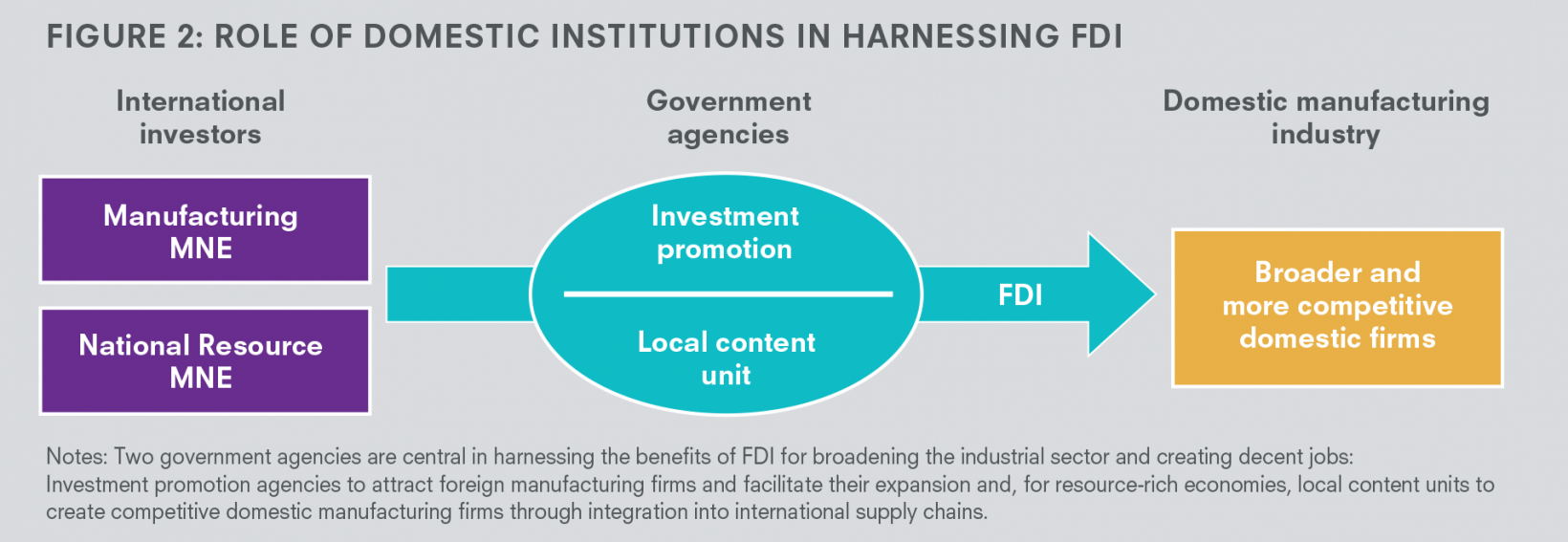

Harnessing the value of FDI requires active procompetition policies that not only attract FDI, but also encourage economic contributions to technology, labour markets and vertical supply chains (Farole & Winkler, 2014; Chen et al., 2015).

Setting up a Local Content Unit in Mozambique

In collaboration with the relevant government ministry, a Local Content Unit (LCU) can engage in dialogue with MNEs to arrive at an optimal solution for local firm involvement in the industrial supply chain. Through a project led by John Sutton, the IGC supported research in Mozambique that evaluated the scope and design of a LCU as the solution to generating more local jobs in the gas industry. The LCU would be an alternative to local content rules, which are often ineffective. A welldesigned LCU that enjoys the full support of the relevant government ministry could achieve the kind of broad-based involvement of local companies and maximise long-term benefits to the Mozambican economy. Based on the study’s suggestion that an LCU can help develop the capabilities of Mozambican firms, improve their quality of outputs to match international standards and create sustainable, high-skilled jobs, the government launched a scoping study to implement an LCU.

For increased FDI to translate into increased productivity, and ultimately economic growth, will depend upon existing linkages between domestic and foreign firms (Newman et al., 2016). The movement of workers and adoption of technologies and work practices are crucial in generating productivity spillovers. In Africa, in contrast to East Asia, linkages between foreign and domestic manufacturing firms are limited, as multinational enterprises (MNEs) often rely solely on imports for intermediate inputs. Many African MNEs produce wholly for export markets, this reduces the scope for forward linkages (Newman et al., 2015). One way to strengthen linkages is through Local Content Units; these are most appropriate when resource-rich economies are in strong positions to impose conditions. In the case of manufacturing, Investment Promotion Agencies have an important role to play as priority must be given to attracting investors and to efforts to remove any impediments to value chain formation.

Figure 2: Role of domestic institutions in harnessing FDI

Policy recommendations

- To accelerate the pace of structural transformation, countries should target FDI in the manufacturing sector. High value-added tradable services, agro-industrial activities and services that directly impact the productivity of modern firms, such as financial services, telecommunications and infrastructure should also be considered.

- To attract FDI to Africa, policies must be put in place to address constraints in three key areas: infrastructure, institutions and incentives.

- On infrastructure, policies should focus on improving access to and reliability of competitively priced electric power, and upgrading the transportation system and ports, as well as improving policies to promote the efficient use of existing infrastructure.

- On institutions, policies should focus on improving investment promotion agencies; export promotion agencies; standards bodies; border control authorities; and customs.

- On incentives, policies should focus on reducing anti-export bias in tariffs and nontariff barriers, on maintaining competitive real exchange rates, and on the potential role for SEZs.

- To harness the benefits of FDI, attention must be given to enhancing the potential for spillovers through backward linkages. The evidence on FDI spillovers shows that the main benefits flow through the domestic supply chains of MNEs (‘vertical linkages’). Thus, encouraging the creation of Local Content Units may be helpful, especially in the case of extractives. Also, efforts to improve backbone network services and financial services can be crucial to further growth in manufacturing.

References

Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P., & Zilibotti, F. (2006). Distance to frontier, selection, and economic growth. Journal of the European Economic association, 4(1), 37–74.

African Economic Outlook (2014). Global Value Chains and Africa’s Industrialisation. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations Development Programme: African Development Bank.

Ansu, Y., McMillan, M., Page, J., & te Velde, D. W. (2016). African transformation forum 2016 Promoting Manufacturing in Africa.

Arvis, J. F., Saslavsky, D., Ojala, L., Shepherd, B., Busch, C., & Raj, A. (2014). Connecting to Compete 2014: Trade Logistics in the Global Economy – The Logistics Performance Index and Its Indicators.

Bende-Nabende, A. (2002). Foreign direct investment determinants in Sub-Saharan Africa: A co-integration analysis. Economics Bulletin, 6(4), 1–19.

Casey, K., Glennerster, R., & Miguel, E. (2011). Reshaping institutions: Evidence on external aid and local collective action. National Bureau of Economic Research. IGC Working Paper. London: International Growth Centre.

Chen, G., Geiger, M., & Fu, M. (2015). Manufacturing FDI in Sub-Saharan Africa.

EY. (2015). EY’s attractiveness survey Africa 2015 – Making choices. www.ey.com/za.

Farole, T. (2011). Special economic zones in Africa: comparing performance and learning from global experiences. World Bank Publications.

Farole, T., & Winkler, D. (Eds.). (2014). Making foreign direct investment work for Sub-Saharan Africa: local spillovers and competitiveness in global value chains. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Freund, C. L., & Rocha, N. (2010). What constrains Africa’s exports? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series, 5184. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Harding, T. & Javorcik, B. C. (2011). Roll out the Red Carpet and They Will Come: Investment Promotion and FDI Inflows. Economic Journal, 121 (557), 1445–76.

Harrison, A., & Rodríguez-Clare, A. (2010). “Trade, Foreign Investment, and Industrial Policy” Handbook of Development Economics. Volume 5, edited by D. Rodrik and M. Rosenzweig, 2010.

Hoekman, B. and Shepherd, B. (2015). Services, Firm Performance, and Exports: The Case of the East African Community. IGC Working Paper. London: International Growth Centre.

Looi Kee, H., Nicita, A., & Olarreaga, M. (2009). Estimating trade restrictiveness indices, The Economic Journal, 2009, vol. 119, p172–199.

Kingombe, C. (2012). Lessons for Developing Countries from Experience with Technical and Vocational Education and Training. IGC Working Paper. 11/1017. London: International Growth Centre.

Lederman, D., Mengistae, T. and Xu, L. (2010). Microeconomic Consequences and Macroeconomic Causes of Foreign Direct Investment in Southern African Economies. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Lederman, D., Olarreaga, M. and Payton, L. (2009). Export promotion agencies revisited. Policy Research Working Paper Series 5125. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Lemi, A. and Asefa, S. (2003). Foreign direct investment and uncertainty: empirical evidence from Africa. Africa Finance Journal 5, 36–67.

Martins, P., Pessoa e Costa, S., and Rienzo, C. (in progress). Developing vocational training in the Mozambique labour market. London: International Growth Centre.

McMillan, M., Rodrik, D., & Verduzco-Gallo, I. (2014). Globalisation, Structural Change, and Productivity Growth with an Update on Africa. World Development Vol. 63, pp. 11–32, 2014.

Moran, T. (2001). Parental Supervision: The New Paradigm for Foreign Direct Investment and Development. Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC.

Newman, C., Page, J., Rand, J., Shimeles, A., Söderbom, M., and Tarp, F. (2016). Made in Africa: learning to compete in industry. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC.

OECD/WTO (2011). Aid for Trade at a Glance 2011: Showing Result.

Prasad, E., Rogoff, K., Wei, S. J., & Kose, M. A. (2005). Effects of financial globalization on developing countries: some empirical evidence (pp. 201–228). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Rodrik, D. (2008). The real exchange rate and economic growth. Brookings papers on economic activity, 2008(2), 365–412.

Sutton, J. and Kellow, N. (2010). An Enterprise Map of Ethiopia. London: International Growth Centre.

Sutton, J., and Zhang, Q. (In progress). Industrial development in historical perspective: the prospects for Sub-Saharan Africa.

UNCTAD. (2015). Foreign direct investment inflows to Africa remained stable in 2014, UN report says [Press release]. Retrieved from: unctad.org/en/pages/ PressRelease.aspx?OriginalVersionID=250.

UNECA. (2013). Harmonizing Policies to Transform the Trading Environment United Nations Commission for Africa. Retrieved from: www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/PublicationFiles/aria_vi_english_full.pdf.

Citation

Sutton, J., Jinhage, A., Leape, J., Newfarmer, R., & Page, J. (2016). Harnessing FDI for Job Creation and Industrialisation in Africa. IGC Growth Brief Series 006. London: International Growth Centre.