Informal settlements and housing markets

Informal settlements and housing markets

Across the developing world, many governments have inherited broken, ex-colonial housing policies that do not work for ordinary residents. While most households in African cities struggle to afford a house for $15,0001, the cost of constructing a basic house that meets all legal requirements is over $42,000 2.

Large-scale ‘public housing’ schemes have not helped matters. The cost of providing this housing means that it is unable to keep up with demand, and often built on less expensive but disconnected urban peripheries. Kigali’s public housing units are cheap compared to other cities, but still cost upwards of $30,000; this is housing for the elite, not for ordinary citizens.

The result of these policy failures is that most people bypass the formal system completely. Urbanisation instead happens through informal settlement, without legal recognition, planning, or formal service provision. Globally, more than one billion people live in informal settlements and this number is set to double in the next fifteen years.

Putting this right will not only dramatically improve living conditions; it will create a huge amount of jobs for young and low-skilled workers to build their city. As the 19th century cities of Manchester and Melbourne rapidly expanded, their primary economic activity was their own construction.

This brief explores practical and realistic ways in which governments can make housing markets work – both to prevent future urbanisation from proceeding informally, and to make existing informal settlements more productive and liveable.

- Providing core infrastructure around which the city can expand is a more realistic policy aim than constructing public housing for everyone.

Providing core infrastructure before people settle is three times cheaper than retrofitting it in existing unplanned settlements, and avoids disruptive and unpopular slum clearance policies. - Small regulatory changes can have a big impact on house prices, and bring ordinary residents into the formal sector.

Making housing affordable for ordinary residents means re-writing old colonial regulations. - Once informal settlement has occurred, land readjustment can enable win-win solutions for occupiers, land-owners and governments.

Through readjustment schemes, infrastructure and planning can be funded by landowners giving up parts of their (more valuable) plots.

Providing infrastructure before settlement

Under current policies, many developing cities are expanding without co-ordination and lacking supporting infrastructure. As a result of unplanned development, many cities only have 10% of their land allocated to roads. The international benchmark is 30%3. Housing has also been built in areas that lack key infrastructure, and where legal ownership of land is unclear. The lack of policy action today is storing up costly problems for the future; infrastructure and land rights are extremely difficult to retrofit. African cities are set to triple in size by 2050, and South Asian cities are set to more than double. Only if governments plan in advance will they get it right the first time. But for plans to actually get implemented, they need to be realistic and prioritise.

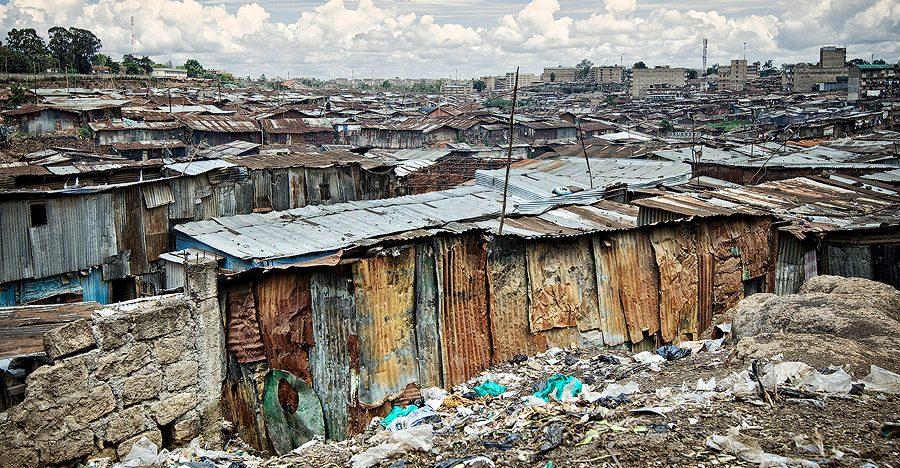

Mathare slum in Nairobi, Kenya. Due to a lack of timely planning, the slum now needs retrofitting. The government lacks the practical authority to do this, and even it did, retrofitting would come at a huge social and economic cost. (Photograph, Claudio Allia, 2009).

Most governments do not have the budget or the expertise to build houses for everyone who comes to the city – but the choice is not between public housing or no plan at all. Instead, governments can provide the core infrastructure around which orderly private development occurs.

In practice, proactive infrastructure provision can be more or less costly depending on the city’s budget:

- At one end of the spectrum, governments can simply demarcate an arterial road grid on the urban periphery, around which settlement can occur. Estimates using figures from Kigali cost this at roughly $100 per household, for a 1km by 1km grid.

- At the other end, governments can provide households with serviced plots; this involves creating a neighbourhood street patter, demarcating and titling land plots, and providing water, sanitation and electricity to the unbuilt plots. Estimates in Kigali cost this at $3,500 per 50m2 serviced plot – 8 times cheaper than Kigali’s $30,000 public housing units. 4

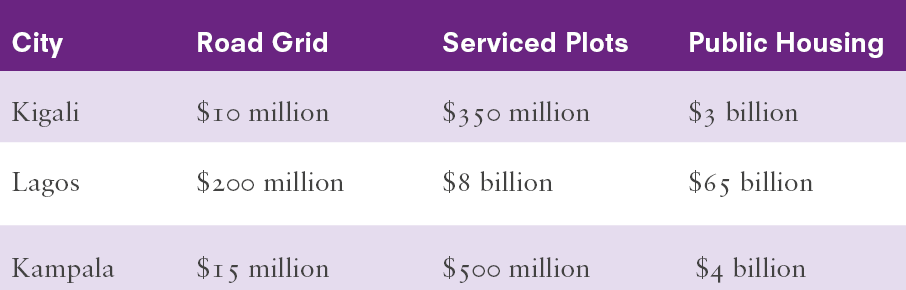

The table below uses housing cost estimates from Kigali to provide a rough estimate of relative cost of various policy options to accommodate the next 10 years of population growth5 in Kigali, Lagos and Kampala (costs are in USD).

Proactive infrastructure provision reduces land costs

By connecting the expanding edges of the city, infrastructure ensures a well-connected supply of land on which the private sector can build. Increasing the supply of urban land reduces land costs throughout the city. Providing infrastructure, particularly transport links, to increase land supply was key to solving housing shortages in London and New York as they developed – and may well be even more crucial in developing cities, where land costs can exceed 80% of total construction costs.6

Road grids and serviced plots

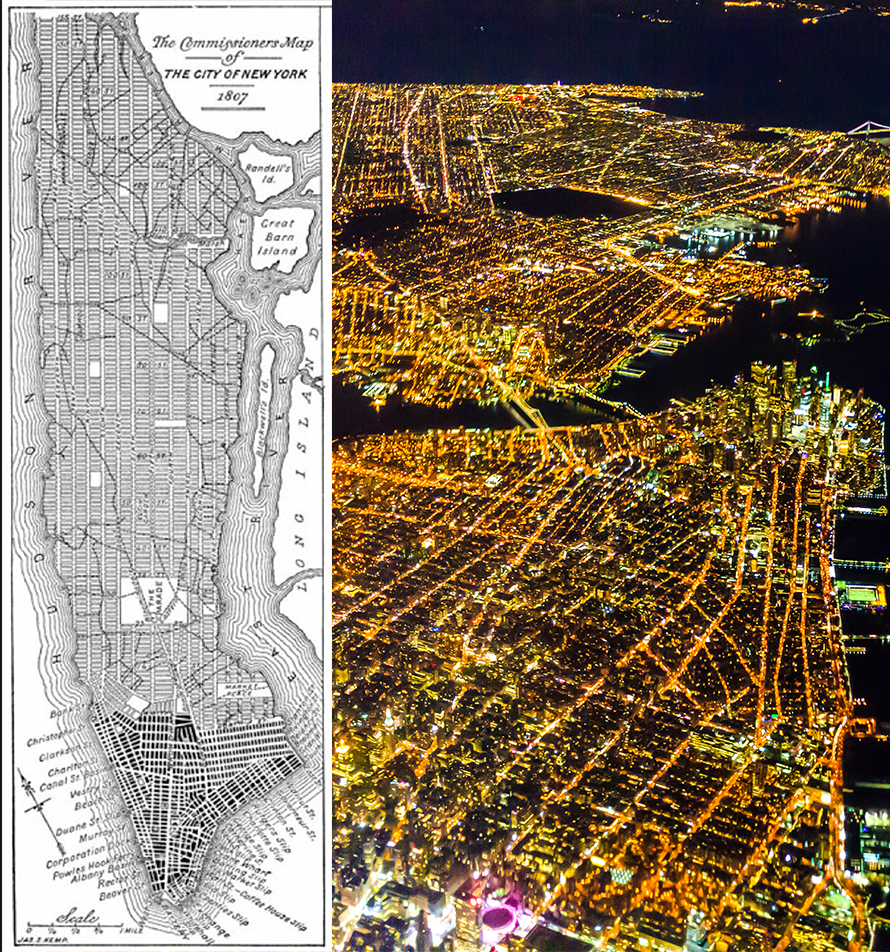

One low-cost way of planning for urban expansion is to build an arterial road grid of dirt roads on the periphery before settlement occurs. This was the approach adopted by the City of New York in their 1811 Commissioners Plan. At the start of the 19th century, the population of New York was just under 100,000 but was estimated to increase five-fold in the next 50 years. In response to this, the city devised a bold plan to expand the urban area of the city seven-fold. This plan mapped and demarcated a grid system of roads on undeveloped agricultural land in Manhattan, leaving roughly 30% of land within the expansion area for public infrastructure uses. Initially, the city only obtained a public right of way over the grid, but as the city expanded, land was acquired to build paved roads, with water and sewerage infrastructure underneath. This enabled structured and connected urban development. By 1900, land within the grid had become fully developed, and a new grid was created for further expansion. The same grid systems created by these plans carries New York’s traffic and infrastructure to this day.

The ‘bare bones’ grid-based approach to urban expansion taken in 1811 New York is currently being drawn upon across many cities in Colombia and Ethiopia. With support from the NYU Marron Institute, governments in these countries are predicting future land requirements for urban expansion based on population growth projections, and obtaining the right of way for a 1km by 1km network of arterial roads on the urban periphery.7

This approach can be particularly useful where public trust in government housing policy is low, because it delivers quick, large-scale and visible results. In Valledupar, a city in northern Colombia, the city has planted trees to line the future road grid, providing a visible and popular signal of proactive planning for urban growth.

The grid system laid down by the 1811 Commissioners Plan is still in place in New York to this day. Left photograph: History of Architecture CCA, 2009, Flickr. Right photograph: New York from the air, Getty Images.

With more resources, governments can focus not only on establishing arterial road networks, but also on creating serviced plots for areas soon to be settled.

The World Bank adopted this approach in its ‘Sites and Services’ programmes in the 1970s and 1980s. These were initially scaled back due to high costs and a perception that the programmes had not led to substantial housing developments. However, these programmes are now being re-evaluated as over time they have paved the way for thriving, and often multi-story neighbourhoods. Recent research from Tanzania has shown that areas which received ‘Sites and Services’ programmes 30 years ago have become better planned, and now have land values over five times higher than other areas which received the same amount of investment in the form of restrospective slum upgrading. 8

Funding infrastructure through rising land values

Installing infrastructure greatly increases the value of land nearby; governments can use this land value appreciation to fund the initial infrastructure investment. In 1811 New York, the city was able to acquire a road grid at very limited cost because the cost of providing compensation to landowners was offset by charging the same landowners ‘betterment fees’. These fees were charged to landowners based on the appreciation in value of the rest of their land – which was now connected to the city. Despite initial opposition, landowners benefitted greatly from this arrangement; agricultural land values skyrocketed once land became part of New York’s metropolis, and more than offset initial losses of land.

Setting the right regulatory environment

Until now, housing development in low-income cities has been largely informal. Informal housing is often highly innovative and entrepreneurial, but a lack of legal recognition or standardisation makes housing difficult to finance on any kind of large scale. Legal recognition and standardisation were both crucial in 19th century Britain as they enabled easy valuations and large-scale financial innovation; individuals were then about to form co-operative ‘building societies’ to pool together savings and finance decent housing.

To make formal housing accessible to ordinary residents, coordinated reforms will need to target the regulatory barriers that drive up formal housing costs. In particular, reforms to land rights and land use regulations can significantly reduce land costs – these are responsible for up to 80% of housing costs in developing cities.

Reforming land rights

Across many developing cities, unclear land rights put urban land in a state of gridlock and paralyses formal housing development. Conflicting land records and weak land governance means land ownership is not secure enough for owners to make substantial property investments, and not marketable enough to enable the transfer of land to those best placed to develop it. 80% of African court cases are disputes over landownership,9 whilst in cities such as Lagos, the cost of property transfer can reach 36% of property value. The result is low-intensity and inefficient use of land: in cities such as Harare and Maputo, 30% of urban land within 5km of the central business district is currently vacant. 10

Enabling urban land markets to work in a way that can facilitate the provision of formal housing typically requires significant investment in land administration systems in advance of large-scale programmes of formal land registration. Research from Peru shows that a large-scale land registration programme in Lima led to a 60% increase in housing investments and a 134% increase in land market transactions. These benefits were made possible by efficient and accessible systems governing transfer and ownership dispute.

Like infrastructure provision, land registration programmes are easier to implement before settlement has occurred. Clear land ownership complements public infrastructure – security of ownership meant that where residents had legal titles in a World Bank ‘Sites and Services’ programme in Senegal, they invested $8.20 for every $1 invested by the World Bank.11 Once an informal settlement is established, clarifying ownership becomes more challenging. Well-connected interest groups often take advantage of this lack of clarity to gain quasi-legal land ownership claims and frustrate attempts at reform.

Reforming land-use regulations

The detrimental effect of land use regulations on house prices has been documented across the world – particularly in those cities which seek to restrict density by setting low building heights, low floor-area ratios and high land plot sizes. Research has shown that these kinds of local regulations in San Francisco have increased housing prices by 20-40% in affected areas.12 Restrictions can be even more distortionary in developing cities, where regulations are based on out-dated colonial planning laws, completely removed from local contexts and income levels. In Dar es Salaam, the minimum housing plot size is 375m2 – as compared to 30m2 in Philadelphia when it was at similar stages of economic development. The majority of urban residents simply cannot afford to purchase land parcels this big. This pushes them into informal housing and hindering the emergence of a large-scale formal housing market. 10

Reforming construction regulations

All cities need construction regulations to ensure safety and standardization across designs. This is particularly important for features of housing units that are not observable to occupiers, such as building materials and construction techniques. Unlike plot sizes and floor areas, occupiers may not be able to identify and make informed decisions on housing based on these features. Construction techniques may therefore require more regulation and standardization to ensure households do not purchase sub-standard or dangerous housing.

But it is also important that such regulations do not constrict housing markets without adequate justification. In many cities, restrictions on functional local building materials in favour of expensive imported materials serve to drive up housing costs significantly, with the end result that most housing does not obey any standard at all. In Kigali, the government is planning reforms to allow the legalization and standardization of high-quality localised construction materials, including fired earth bricks, to reduce housing informality and encourage local construction sector growth.

In many cities, reforms to construction regulations to allow for ‘incremental housing’ solutions can allow the private sector to provide housing at a far lower cost than would otherwise be possible. ‘Incremental housing’ programmes provide just the parts of a house which owners are less able to provide themselves (such as foundations and roof structure), enabling owners to invest in completing their house as and when they earn the money to do so.

Housing designs by Elemental in Chile have enabled incomplete, lowcost housing (left) to be delivered to low-income residents and completed by them over time (right).

Policy towards existing informal settlements

Where informal settlements have already been established, policy options become more challenging. These options can broadly be divided into slum-upgrading, resettlement and land readjustment policies.

Slum upgrading

Where policymakers are content to retain land under residential use, participatory in-situ slum upgrading is a cost-effective way to enable neighbourhoods to incrementally transform into dense and liveable places. Whilst infrastructure may be cheaper to reconstruct elsewhere on a greenfield site, housing and businesses already established in these settlements are very expensive to reconstruct adequately, and the socio-economic networks developed may be impossible to relocate.

Upgrading programmes can also focus on key low-cost infrastructure or housing improvements, rather than reconstructing the whole house.

Gradually, upgrading programmes can enable informal settlements to transform into dense and liveable neighbourhoods that integrate the city’s low-income workforce into the urban fabric.

Smaller upgrading programmes typically focus on short-term priorities such as public health. These are generally best identified in close collaboration with local communities.

In the longer term, however, more significant integration of informal settlements into the city typically requires more comprehensive investments: better transport links and regularisation of land rights. Installing transport infrastructure is challenging because of costly and complex resettlement that relies on clarity of land ownership. Regularising land rights in turn presents a significant challenge in part because official land titling procedures are often very expensive, and in part because land ownership in informal settlements is often either undocumented or contested.

Rwanda’s 2009-13 land tenure regularisation programme may offer useful lessons for other low-income cities in overcoming these challenges. Instead of requiring lengthy legal proceedings and complex surveying technologies to register land, communities openly demarcated their plot boundaries and resolved disputes together. This was done with the help of a local judicial authorities and a local parasurveyor. Through this process, almost all land in the country was registered in under five years, and at a cost of only $6 per parcel. By contrast, in Tanzania, the cost of official mapping and surveying procedures can reach over $3,000. 14

Such solutions may not work so effectively in all political settings. In many cases, clarifying land ownership requires city authorities to deal with well-connected ‘slum lords’, who have exploited the lack of governance in informal settlements to make their own land ownership claims. In Kibera, Nairobi, for example, 50% of land is informally owned by well-connected government bureaucrats;15 they obtain rents through this ownership, but their rights are too weak to build on substantially or to sell to developers. 16

City governments often do not have the authority to break this stalemate, and so national leaders will need to step in. Given the importance of inner-city development for national economic growth, well-connected slumlords will either need to be faced down or bought out through compensation so that land can be reassigned to government or to existing residents. Even if compensation is necessary, it is often far less costly than the wasted productive potential that results from the current gridlock. One current estimate puts the cost of land misallocation in Kibera, a slum in central Nairobi, at over $1 billion. The market value of titled land would be high enough for each slumlord to be compensated at the value of all their future rents, and each tenant household to be compensated with £16,000 (roughly 25 years’ worth of rent payments).

Different types of land rights and the transformation of land use

Depending on government plans for future land use, different policies towards land rights will be needed for existing informal settlements. Often the best policy is to formally register individual land titles, and allow the private sector to freely buy and sell land in line with the changing economic activities of the city. However, if for reasons of social cohesion policymakers want to assist communities to remain in place, collective land rights may be appropriate. This typically means the whole community has to agree to selling the land of the informal settlement rather than individual households selling gradually.

Resettlement

Resettlement programmes are extremely costly, both to governments and to the communities affected. However, given the unplanned nature of existing development in many cities, there is likely to be some need for resettlement of informal residents. There are typically two reasons given for this: to improve the lives of those living in an informal settlement, or to redirect the land of the informal settlement for an alternative use. If the former is the aim, resettlement is unlikely to be the most cost-effective way to improve living conditions unless the settlement is located on land which is genuinely unsafe.

Even when voluntary, resettlement often harms residents

In Ahmedabad, India, in 1987, the Self-Employed Women’s Association organised a lottery whereby 110 winning households signed leases to relocate from inner-city slums to government housing seven miles away. Winners received a 50% reduction in monthly rent, as well as the possibility of eventual home ownership. However, despite far better amenities in the new housing, only two-thirds of winning households actually chose to relocate, and only one third were still in the new housing in 2007. Better living conditions could not compensate for the break-up of community, and loss of socio-economic networks created by the resettlement. 17

If the aim is to improve land use, this can be justified in order to make space for vital infrastructure for the productivity and liveability of the city as a whole, or to facilitate private investment with large-scale employment potential. Resettlement for public infrastructure may be particularly important in African cities, where the density of paved roads is less than a quarter of that in other low-income cities. However, ‘economic regeneration’ projects are clearly subject to abuse, with many such projects used to justify construction projects that are of dubious value to the city as a whole, or simply to assemble land to be held for speculative purposes.

When the city does decide to embark on a resettlement programme, one key debate centres around compensation. A benchmark for compensation typically combines:

- Payment to landowners at the market value of their land and property before redevelopment projects are announced. This prevents speculative land investments being made after the project, and driving up the price of land being acquired. In Kampala, compensation payments for public infrastructure are based on land values after projects are announced – this has made infrastructure prohibitively expensive, and risks blocking the growth prospects of the whole city. As a result, the road connecting Kampala to its airport is the most expensive road per kilometre in the world.18

- Further compensation for displacement to resident households and businesses in the form of compensation for lost business profits, lost employment opportunities and relocation costs.

Ensuring this happens in practice means making compensation laws clear and specific. Without this, well-connected individuals will be able to exploit legal loopholes and claim unrightful compensation.

Land readjustment

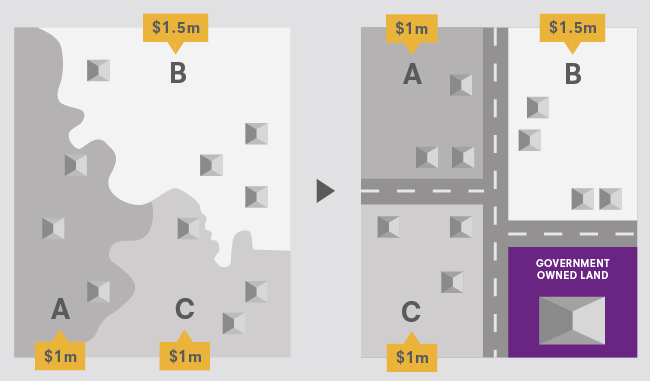

Land readjustment schemes allow governments to unlock often substantial land values in informal settlements to facilitate neighbourhood transformation. Under these schemes, governments pool together privately held land plots and creates a new land use plan for the whole area. These plans include new infrastructure provided by the government, which increases the value of each surrounding plot. Because land values rise due to better planning and infrastructure provision, private landowners are willing to give up some of their land to the government to fund the scheme. In South Korea, landowners agreed to release up to half of their land under land readjustment schemes in the 1940s, and over half of the land area of Seoul was redeveloped in this way. This enabled public investments in infrastructure and public spaces to be largely self-financing. 19

Land readjustment schemes

Government pools private land plots and creates a new land use plan for the whole area. Because land values rise due to better planning and infrastructure, private landowners are willing to give up some of their land.

Tenure disputes can also be resolved in this process through ‘land-sharing’ arrangements between official landowners and occupants. Within the new neighbourhood design, long- term occupants can be resettled in higher density accommodation, financed by freeing up previously unusable land for the owner to be used for high-value commercial or residential use.

Land readjustment schemes require effective and empowered implementing institutions – not least because landowners need to trust in government if they are to be willing to give up substantial portions of their land. Angola offers a striking example of two diverging experiences with land readjustment based on different institutional structures following a change in law in 2007.

In one successful scheme, revenues from the sale of some of the land given up by private owners went into an infrastructure development fund to cover the costs of infrastructure provision. By contrast, in a second scheme, all local revenues reverted to central government, disincentivizing local government from raising incomes from land sales. Instead, land parcels were distributed for free, and no funding was recovered to invest in infrastructure. Wealthy landowners gained control over the replotting process, and used it simply to increase their landholdings.

Further reading

Lamson-Hall, P., Angel, S , DeGroot, D., Martin, R. and Tafesse, T. (2018) “A New Plan for African Cities: The Ethiopia Urban Expansion Initiative” Journal of Urban Studies

Lucci, P., Bhatkal, T., Khan, A. and Berliner, T. (2015) “What works in improving the living conditions of slum dwellers: A review of the evidence across four programmes”, Overseas Development Institute, Dimension Paper 04

Lozano-Gracia, N., Young, C., Lall, S. V., and Vishwanath, T. (2013). “Leveraging Land to Enable Urban Transformation: Lessons from Global Experience.” Policy Research Working Paper; No. 6312. World Bank, Washington, DC.