Making the workplace work for women

The traditional economic rationale for increased female labour force participation is that it benefits women directly and society indirectly. A new argument looks at how increased female labour force participation can boost aggregate economic growth and hence, benefit everyone, on average. Yet, several factors hinder women’s productive employment.

This Growth Brief presents International Growth Centre (IGC) and related research on the key factors that constrain female labour force participation (FLFP) in developing countries and strategies to address these constraints. The discussion is structured by ‘spaces’, with a focus on social and cultural norms in the home space; issues of safety and mobility in the public space; and gender inequities and lack of enabling conditions in the workplace. Many of these barriers are cross-cutting – particularly norms – and interlink across spaces.

-

IGCJ7591-Growth-Brief-Making-the-Workplace-Work-for-Women-191007-WEB.pdf

PDF document • 434.81 KB

Introduction

At 49%, the global female labour force participation (FLFP) rate is 27 percentage points below that of men. While the gap has narrowed since 1990, the rate of progress has been slowing and is expected to halt, or even reverse, by 2021. Further, there are considerable differences across countries at different stages of development (International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2018).

Innate abilities are presumably uniformly distributed across genders and firms should ideally be able to tap into the best talent. However, if half of the potential talent pool faces artificial barriers in joining the labour force, the choice set shrinks, which is sub-optimal for economic growth at large.

New International Monetary Fund research (2018) shows that if the strong complementarities between women and men in production are accounted for, the economic benefits of adding women workers are possibly larger than previously suggested. For countries ranking in the bottom-half for gender equality, closing the gender gap could increase gross domestic product by 35% on average – one-fifth of this gain is due to the gender diversity effect on productivity.

Women’s work participation is also intrinsically desirable: When women take up paid work outside the home, they are likely to have greater bargaining power within the household, which has positive effects on their well-being and that of their families (World Bank 2001).

This Growth Brief presents International Growth Centre (IGC) and related research on the key factors that constrain FLFP in developing countries and strategies to address these constraints. The discussion is structured by ‘spaces’, with a focus on social and cultural norms in the home space; issues of safety and mobility in the public space; and gender inequities and lack of enabling conditions in the workplace. Many of these barriers are cross-cutting – particularly norms – and interlink across spaces.

Key messages:

- Cultural and social norms, and their manifestations, prevent women from realising their full economic potential. In many societies, a preference for sons puts girls at a disadvantage in terms of human capital investment by families, and ownership and control of assets. Early marriage and childbearing also limits girls’ education and workforce participation. Moreover, married women face ‘time poverty’, as domestic chores and childcare are primarily considered ‘women’s work’.

- Safety concerns restrict women’s physical and economic mobility. In some contexts, women are unable to move around freely due to safety concerns and the perception that public spaces are ‘male spaces’. Besides weak rule of law, these challenges are linked to norms around gender segregation. This constrains women’s workforce entry and progression, access to education and skilling, and to professional networking opportunities.

- Gender inequities and lack of enabling conditions in the workplace keep women away. Women in the labour force are not given equal opportunities and remuneration vis-à-vis men. The workplace also lacks enabling conditions to support women in managing dual responsibilities at work and home effectively. Further, the insufficient creation of desired jobs interacts with norms around women’s role in home production to adversely impact female employment.

Key message 1 – Cultural and social norms, and their manifestations, prevent women from realising their full economic potential

Historically, in many developing countries, families have a pro-son bias. Consequently, they are less invested in their daughters’ human capital, particularly in terms of career-oriented skill development. Hence, women become disadvantaged as potential entrants to the productive workforce.

In an IGC experiment in Ghana, Duflo et al. (2012) find that girls are less likely to pursue secondary education even when the financial barrier is removed. Students who passed secondary school entrance exams but could not enrol for financial reasons were randomly awarded scholarships: Only 64% of female awardees enrolled vis-à-vis 81% of boys.

Early marriage and childbearing are common among girls in developing countries, and this limits their human capital accumulation and labour force participation. IGC research in Uganda (Bandiera et al., 2018) finds that providing adolescent girls vocational training and information on sex, reproduction, and marriage makes them 4.9 percentage points more likely (48% increase over baseline levels) to engage in income-generating activities.

Studying the long-term effects of a one-time targeted transfer – cash for school girls to buy bicycles – by the government in Bihar, India, Mitra and Moene’s (2017) IGC research finds that the programme empowered girls and raised their aspirations. The beneficiaries were more likely to complete their education, look for more productive work outside agriculture, and delay marriage and childbearing. These positive outcomes also reflect some improvements in the attitude of others towards girls. Yet, many of the ‘cycle girls’ reported that their families did not permit them to work, an indication that some social norms stuck or would need more time to change.

Work in Saudi Arabia by Bursztyn et al. (2018) suggests that female labour supply may also be constrained by misperceived social norms: While a vast majority of young married men in Saudi Arabia privately support FLFP outside of home from a normative perspective, they substantially underestimate the level of support for FLFP by other similar men. Correcting these beliefs about others increases married men’s willingness to let their wives work (as measured by their costly sign-up for a job-matching service for their wives) as well as the wives’ likelihood to have applied and interviewed for a job four months after the intervention.

In developing countries, women are less likely to own assets such as land – they either do not have the legal right to inherit parental/ancestral property, or families choose to not bequest property to daughters. Women also do not have much control over household resources. Since loans typically require collateral, this constrains female entrepreneurship. In an IGC project undertaken in collaboration with the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) in India, Field et al. (2016) find providing microfinance to women helps integrate them into the workforce in the long-run by supporting greater participation in household business activities.

Yet another manifestation of social and cultural norms is ‘time poverty’ among married women. Even when women are educated and allowed to work outside the home, they simply may not be able to do so because they disproportionately bear the burden of the care economy. IGC research in Uganda by Ali et al. (2015) shows that women’s greater childcare responsibilities explain two-fifths of the gender gap in agricultural productivity. In general, the issue of time poverty among women is an important area for further research. There is a data gap as time-use surveys are expensive and difficult to implement.

Influencing gender attitudes among adolescents in Haryana, India

Dhar et al. (2018) conducted a baseline survey, as part of an IGC project, to assess gender attitudes among 14,809 adolescent boys and girls in middle school and 6,126 parents in the Indian state of Haryana in 2013–2014. They used measurement tools such as self-reported attitudes surveys, psychological experiments, and a computer-based psychometric tool called the Implicit Association Test (IAT).

Gender attitudes were found to be quite regressive: For example, about 80% of boys and 60% of girls believed a woman’s most important role is being a good homemaker. In general too, girls were less likely than boys to endorse gender-discriminatory views.

The researchers have undertaken a multi-year intervention aimed at eroding support for restrictive gender norms – among both boys and girls – which involves engaging adolescents in classroom discussions about gender equality. They find the intervention substantially increased adolescents’ support for gender equality, even though there are other factors influencing their gender attitudes, such as their parents’ views. Programme participants also report more gender equitable behaviour; for instance, boys report helping out more with household chores.

Key message 2 – Safety concerns restrict women’s physical and economic mobility

In many countries, women face distinct challenges in accessing public transport. They feel unsafe walking to transportation stops and waiting at them. There are concerns over harassment and worries about social reputation, causing stress and discomfort (Sajjad et al., 2017, based on work in Pakistan). Besides weak rule of law, these challenges are linked to patriarchal norms around gender segregation that forbid women from coming into contact with men that are not their relatives. Consequently, less women access public spaces, perpetuating the perception of public spaces as ‘male spaces’.

Borker (2018) surveyed 4,000 students at Delhi University, India and found that women are willing to choose a college in the bottom-half of the quality distribution over a college in the top 20%; spend US$290 more annually on commuting than men; and travel 40 minutes more daily, for a transport route that is perceived to be safer.

The inability to travel freely constrains not just female education, skilling, and entry into the workforce, but also career progression. Women may turn down promotions if senior roles involve working late hours and/or travelling away from home. Similarly, female entrepreneurs may ‘choose’ to keep their businesses small. Given the restrictions on physical mobility, women tend to have weaker social networks and hence, may lose out on peer/mentor learning, and work-related information.

Field et al. (2015) find that when female customers of SEWA Bank, India, are given business skills training along with a friend they are more likely to take a loan and to use it for business purposes. These women were also found to have significantly higher household income and consumption levels four months after the intervention, and were less likely to report their occupation as housewife. Those who belonged to more restrictive social groups were particularly sensitive to peer involvement.

Women also find it harder to migrate for work, on account of safety concerns and family-related challenges. In an IGC project examining a large vocational training programme in India, Moore et al. (2018) find that while women are overall less likely to receive and accept job offers as compared to men, the gender gap in accepting jobs becomes much wider when the job involves moving away from home. Provision of migration support is seen to be associated with higher workforce participation and longer job tenures.

Lahore’s pink buses

In Lahore, Pakistan, the government introduced women’s-only “Pink Buses” on three routes in the city in 2012. The service operates on the same routes as regular buses that have separate sections for women. It makes 2–4 trips a day, finishing services by 3 pm. The programme is heavily subsidised and suffers from high financial losses as ridership is low.

In an IGC study led by Sajjad et al. (2017), the researchers conducted a survey of 81 Pink Bus passengers and six Pink Bus conductors to learn more about the user base and assess the programme’s strengths and areas for improvement.

The researchers conclude that while the government’s efforts to facilitate women’s ability to commute safely are commendable, the resources for these services could be utilised more efficiently.

Key findings:

- While Pink Buses benefit their users substantially, they serve a very small fraction of women. There are several other women in the city and its peri-urban areas who do not even have access to a bus with a separate women’s compartment.

- Since the bus arbitrarily completes 2–3 round trips per day on one of the routes, passengers cannot always plan their travel around bus timings. At least 35% of surveyed passengers felt that the service should run until the evening as they cannot use it for their return trip – a major shortcoming for working women.

- Many women travelling on regular buses along the routes are not aware of the service.

Key message 3 – Gender inequities and lack of enabling conditions in the workplace keep women away

Women in the workforce are often discriminated against in terms of opportunities and remuneration, even when they possess the required education and skills. According to the ILO’s Global Wage Report 2018/19, weighted global estimates of the gender pay gap range from about 16% to 22%, depending on the measure used.

Other forms of gender inequities exist in the workplace. Ashraf et al. (2018) hypothesise that female entrepreneurs may be disproportionately harmed, relative to men, by weak rule of law. For example, women may avoid dealing with men in business for fear of expropriation or violence. The experiment with entrepreneurs in Zambia shows improving legal institutions reduces or eliminates the gender gap in trusting business partners or other entrepreneurs in the context of economic activity.

Additionally, workplaces in many countries often lack conditions that can support women in fulfilling their dual responsibilities at work and home effectively. These conditions include the right to paid family leave and to come back to equivalent work; flexible hours; fairly compensated home-based work; and access to good quality and affordable childcare facilities. There is also the grave issue of sexual harassment in the workplace. The effects of these factors on FLFP are important areas for further research.

Demand side matters

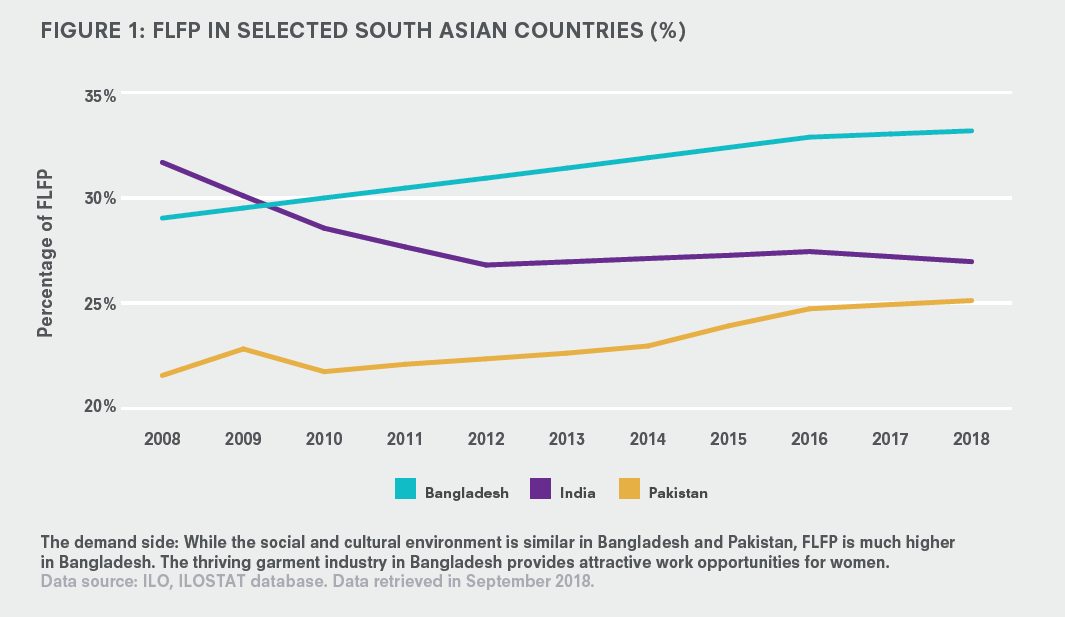

In addition to the ‘supply-side’ factors discussed in the first two key messages, FLFP is influenced by the ‘demand side’: The nature of available employment options.

Goldin (1995) hypothesised that FLFP is U-shaped across the process of economic development: It first declines and then rises. Initially, when incomes are low and agriculture is dominant, FLFP is high as women work on family farms. As production moves to the wider market, FLFP falls because of the social stigma associated with women undertaking manual work away from home – the only kind of wage labour available to those with low levels of education.

Given the low potential earnings of manual work, which are effectively even lower for women because of the social costs, combined with the presence of higher household incomes, women retreat into the household. As women’s education improves, better work opportunities become available to them that are more socially acceptable and pay well, encouraging women to re-enter the workforce.

However, in some developing countries, the creation of desirable jobs has not kept pace with the supply of educated workers. This interacts with norms around women’s role in domestic production, resulting in an adverse impact on the employment prospects of women.

In IGC research, Afridi et al. (2018) analyse nationally representative data from India and find that despite a decline in fertility and broad increases in female educational attainment over the past two decades, the share of working women has fallen over time.

The trend is driven by rural, married women: A possible reason is that their work preferences and reservation wage (the lowest wage at which a worker would be willing to accept a particular type of job) have changed due to an increase in their education, but there has not been a commensurate increase in work opportunities outside of agriculture (Chatterjee et al. 2015). Hence, they are choosing to stay at home – higher incomes of spouses enable them to do so – and investing their time in developing the human capital of their children, for which the returns are rising.

Female factory workers in Bangladesh face a glass ceiling

Data from garment factories in Bangladesh show that four out of every five production workers are women. In contrast, just over one in 20 supervisors is a woman. In an IGC project, Naeem et al. (2014) worked with local training companies to provide supervisor training to four female sewing machine operators and one male operator per factory, in about 60 ready-made garment factories in Bangladesh.

While female trainees outperform male trainees in management simulation exercises, they are less likely to be tried out or promoted. They also find evidence from survey responses and exercises that suggests female trainees face some initial resistance as supervisors, which could account for lower initial performance on the line. The resistance is rooted in social and cultural norms that do not accept women in positions of authority, and also male workers considering this to be an impediment to their own career progression.

Figure 1: FLFP in selected South Asian countries (%)

Policy recommendations

A multitude of interlinked factors constrain FLFP. A holistic approach is needed to address these barriers and integrate women into the workforce.

- Educating women may not in itself ensure FLFP, but it is the foundation for women’s productive employment. As parents may discriminate against daughters in terms of human capital investment, government policy and programmes should actively promote education and formal skills training for girls.

- Interventions are needed to address the practices of early marriage and childbearing, which negatively impact human capital accumulation and labour force participation among women.

- Investment in female education and skilling, as well as delayed marriage and childbearing, are more likely if there is creation of sufficient ‘good’ jobs commensurate with the general increase in education levels in developing countries.

- Gender equity requires a drastic shift in cultural norms. Adolescence may be an effective time to shape gender attitudes, aspirations, and behaviours in the long run. This can be achieved through sensitisation campaigns in schools. There should be particular emphasis on boys as they are likely to be involved in the labour supply decisions of female family members in the future.

- Access to affordable, reliable childcare facilities and the provision of family leave can enhance FLFP among women.

- Improving access to public services such as drinking water and clean fuel can support married women in managing their domestic duties more efficiently, leaving time for undertaking paid work.

- Since the acceptance of women in public spaces can only increase slowly, as more and more women step out of their homes, some measures of segregation and safety will be needed in the short term to encourage women’s mobility. Besides ensuring stronger rule of law, these may include provision of separate women-only sections on buses and trains, adequate street lighting, CCTV cameras at bus stops, helplines, and so on, and the presence of more female police officers in public spaces.

- Gender parity in work and pay may encourage more women to join the labour force.

- Stronger legal institutions can reduce the gender gap in trust and economic activity among entrepreneurs.

- The provision of credit, along with business skills training and the facilitation of networking among beneficiaries, can encourage female entrepreneurship.

- Providing migration support to women can enable them to take jobs away from home. This may take the form of assistance in finding accommodation, opening a bank account, or finding medical help.

- Good quality time-use data should be periodically generated to better understand the issue of time poverty among women.

References

Afridi, Farzana, Dinkelman, Taryn and Mahajan, Kanika (2018). “Why Are Fewer Married Women Working in Rural India? A Decomposition Analysis over Two Decades”, Journal of Population Economics, 31(3): 783–818, July. Accessible: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148–017–0671-y

Ali, Daniel, Bowen, Derick, Deininger, Klaus and Duponchel, Marguerite (2015). Investigating the gender gap in agricultural productivity: Evidence from Uganda, Policy Research Working Paper 7262, World Bank Group. Accessible: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/172861468184777211/pdf/WPS7262.pdf

Ashraf, Nava, Delfino, Alexia and Glaeser, Edward (2018). Women, Entrepreneurship, and Institutions, International Growth Centre Policy Brief. Accessible: www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/

Ashraf-Delfino-2018-policy-brief.pdf

Asian Development Bank (2016). Policy Brief on female labor force participation in Pakistan, No. 70, October.

Bandiera, Oriana, Niklas Buehren, Robin Burgess, Markus Goldstein, Selim Gulesci, Imran Rasul and Munshi Sulaiman (2018). Women’s empowerment in action: Evidence from a randomized control trial in Africa. Accessible: www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctpimr/research/ELA.pdf

Borker, Girija (2018). Perceived risk of street harassment and college choice of women in Delhi, VoxDev. Accessible: https://voxdev.org/topic/health-education/perceived-risk-street-harassment-and-college-choice-women-delhi

Bursztyn, Leonardo, González, Alessandra L and Yanagizawa-Drott, David (2018). “Misperceived social norms: Female labor force participation in Saudi Arabia”, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 24736. Accessible: www.nber.org/papers/w24736.pdf

Chatterjee, Urmila, Murgai, Rinku and Rama, Martin (2015). Job opportunities along the rural-urban gradation and female labor force participation in India, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7412.

Dhar, Diva, Jain, Tarun and Jayachandran, Seema (2014). Tell us what you really think: Measuring gender attitudes in Haryana, Ideas for India. Accessible: www.ideasforindia.in/topics/social-identity/tell-us-what-you-really-thinkmeasuring-gender-attitudes-in-haryana.html

Dhar, Diva, Jain, Tarun and Jayachandran, Seema (2018). Reshaping adolescents’ gender attitudes: Evidence from a school-based experiment in India, Working Paper.

Duflo, Esther, Dupas, Pascaline and Kremer, Michael (2012). Estimating the benefit to secondary school in Africa: Experimental evidence from Ghana, Working Paper F-2020-GHA-1, International Growth Centre. Accessible: www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Duflo-Et-Al-2012-Working-Paper.pdf

Field, Erica, Martinez, Jose and Pande, Rohini (2016). Does women’s banking matter for women? Evidence from urban India, Working Paper S-35306-INC-1, International Growth Centre Working Paper. Accessible: www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Field-et-al-2016-Working-Paper.pdf

Field, Erica, Jayachandran, Seema, Pande, Rohini and Rigol, Natalia (2015). Friendship at Work: Can Peer Effects Catalyze Female Entrepreneurship?, Harvard Kennedy School, Working Paper Series 15–019.

Hsieh, Chang-Tai, Hurst, Erik, Jones, Charles I and Klenow, Peter J (2019). The allocation of talent and US economic growth. Accessible: http://klenow.com/HHJK.pdf

International Labour Organization (2018). Global wage report 2018/19: What lies behind gender pay gaps. Accessible: www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_650553.pdf

International Labour Organization (2018). Labor force participation rate, female (% of female population ages 15+) (modeled ILO estimate). Accessible: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS

International Labour Organisation (2018). World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends for Women. Accessible: www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/trends-for-women2018/WCMS_619577/lang–en/index.htm

Mitra, Shabana and Moene, Karl Ove (2017). Wheels of power: Long-term effects of targeting girls with in-kind transfers, International Growth Centre Working Paper. Accessible: www.theigc.org/

publication/wheels-of-power-long-term-effects-of-targeting-girls-with-in-kind-transfers/

Moore, Charity, Rohini Pande, Troyer and Prillaman, Soledad Artiz (2018). Vocational training programs in India are leaving women behind but this needn’t be the case, International Growth Centre Blog. Accessible: www.theigc.org/blog/vocational-training-programs-india-leaving-women-behind-neednt-case/

Naeem, Farria and Woodruff, Christopher (2014). Managerial capital and productivity: Evidence from a training program in the Bangladeshi garment sector, International Growth Centre Policy Brief. Accessible: www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Macchiavello-et-al-2014-Policy-Brief.pdf

Sajjad, Fizzah, Anjuman, Ghulam Abbas, Field, Erica and Vyborny, Kate (2017). Gender equity in transport planning: Improving women’s access to public transport in Pakistan, International Growth Centre Policy Paper. Accessible: www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Sajadd-et-al-policy-paper-2017_1.pdf

World Bank (2001). Engendering development: Through gender equality in rights, resources, and voice, World Bank and Oxford University Press.

Note: Bold text denotes IGC-funded studies