Growth brief: Taxing to develop - When 'third-best' is best

Effective tax policy design is the foundation of strong economic development. Barriers to tax collection limit governments’ abilities to finance public goods and services, and invest in infrastructure to spur economic growth.

-

IGCJ4293_Taxing-to-develop_WEB-FINAL.pdf

PDF document • 319.28 KB

Introduction

Taxes are a channel of reciprocal exchange between citizens and governments. Taxes increase government accountability, encourage better governance, public service delivery and enforcement of law and order for the protection of citizen rights – essential ingredients for economic growth. Without widespread monitoring and reporting systems to capture and verify financial transactions, many developing country tax systems generate low tax-to-GDP ratios. Effective tax policies must also address tax morale and administration.

Inability to tax is both a symptom and cause of underdevelopment. In countries with large informal economies, tax policies must account for gaps in monitoring, reporting, and administration to overcome barriers to tax enforcement and collection. Developing country governments are often characterised by poor public service delivery. Without the benefits of public goods and services, citizens have few incentives to pay taxes.

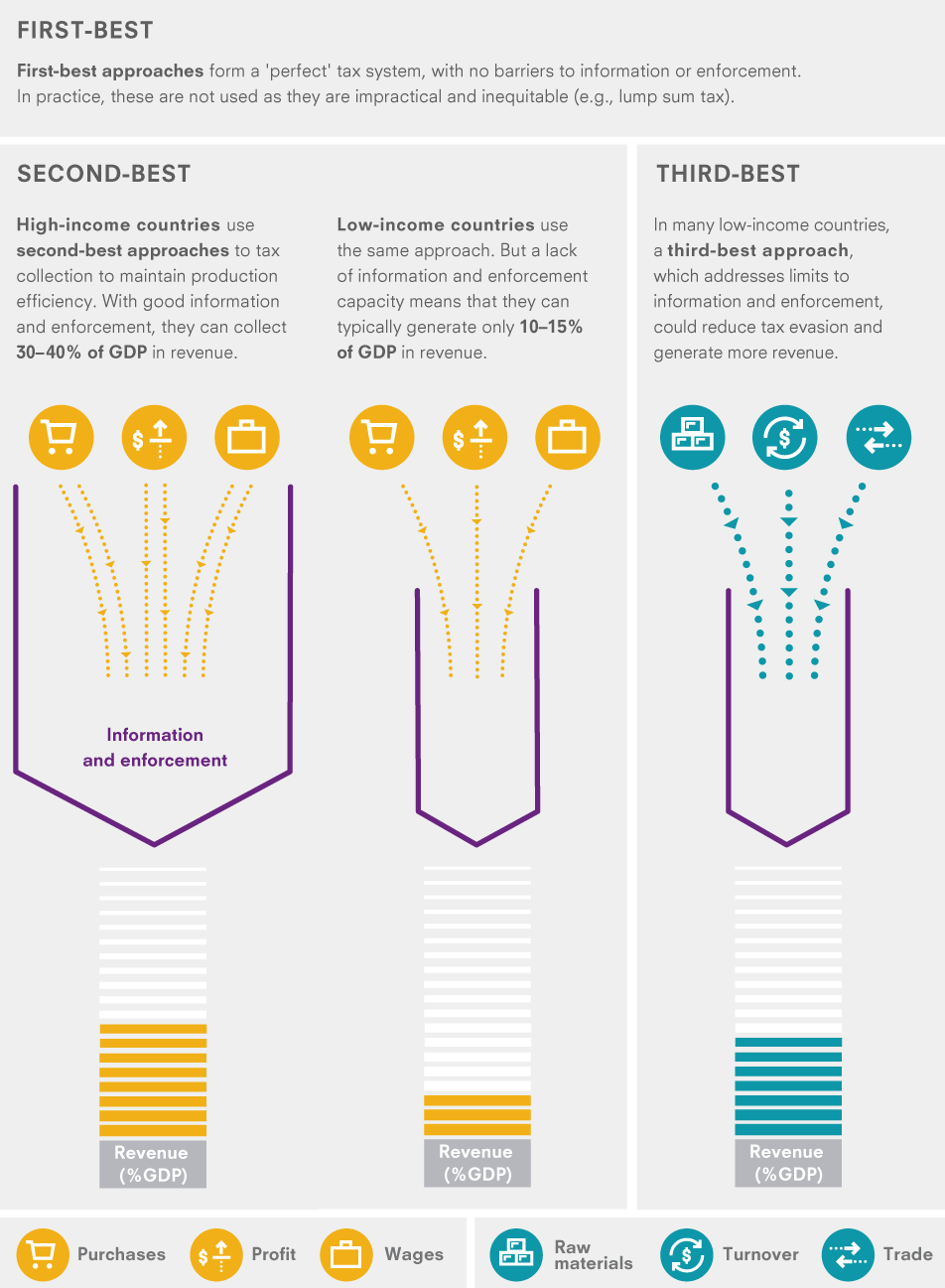

This brief presents a rethinking of tax policy. Traditional tax models assume a ‘second-best’ approach where, in the absence of perfect information (‘first-best’ conditions), tax authorities face some informational barriers to tax collection. Our approach, characterised as ‘third-best’, assumes that developing country tax authorities face severe informational barriers and significant enforcement constraints.

Given the central importance of tax revenues to financing public services, there is no viable alternative to building effective tax systems. Third-best measures, addressing information and enforcement challenges, could yield significant revenue gains in developing countries.

See our infographic on 'third-best' here.

Key Messages

-

Overcoming barriers to tax policy enforcement requires greater access to information

Large informal economies with limited digital coverage of financial transactions make monitoring, verifying, and enforcing tax liabilities a challenge in developing countries. Policies must address enforcement gaps and strengthen information trails.

-

Third-best policies, inefficient in developed countries, may prove efficient in developing countries

The barriers to information and enforcement that plague developing countries require experimentation and policy innovation. Although taxes of inputs, turnover, and trade, are traditionally considered production inefficient, gains in revenue efficiency may significantly offset losses from production efficiency.

-

Harnessing social incentives may increase compliance

Non-monetary incentives affect tax morale and compliance. Harnessing social and non-monetary incentives may provide a cost-effective mechanism for raising compliance.

-

Motivating tax collectors could bridge wider enforcement gaps

Effective administration systems are crucial to tax collection. Smart interventions like pay-for-performance can incentivise better performance by tax collectors.

Key message 1 – Overcoming barriers to tax policy enforcement requires greater access to information

Tax collection requires effective enforcement mechanisms. For this, governments must have the capacity to monitor and verify taxable financial transactions. This is a particularly vexing problem for developing country governments where a significant proportion of the labour force is engaged in informal employment (Auriol & Warlters, 2005).

The prevalence of informal or unregistered labour within developing countries reduces the proportion of financial transaction data that flows through verifiable channels. Without access to third-party verifiable transaction data, modern tax instruments are much less effective at monitoring and enforcing tax payment.

Modern tax systems rely on comprehensive systems of verifiable information reported by third-party institutions (e.g. employers, banks, and investment or pension funds). These explicit thirdparty verified information trails form the basis of a modern government’s tax enforcement capacity. Explicit information is reinforced through various implicit information trails. Implicit information is typically created through transactions between the taxpayers and third-party agents (e.g. credit card records, mortgages, contracts, etc.) and functions as a supplemental means of monitoring and verifying any self-reported or non-third-party reported income.

Both explicit and implicit information trails rely on widespread coverage of reporting and documentation to generate traceable financial flows – but this is often missing in developing country tax systems. Access to high-quality explicit and implicit information trails allow governments to systematically compare third-party reported information with selfreported tax returns in order to uncover discrepancies or detect tax evasion. This intrinsically raises the costs of non-compliance by taxpayers and, consequently, increases revenues collected.

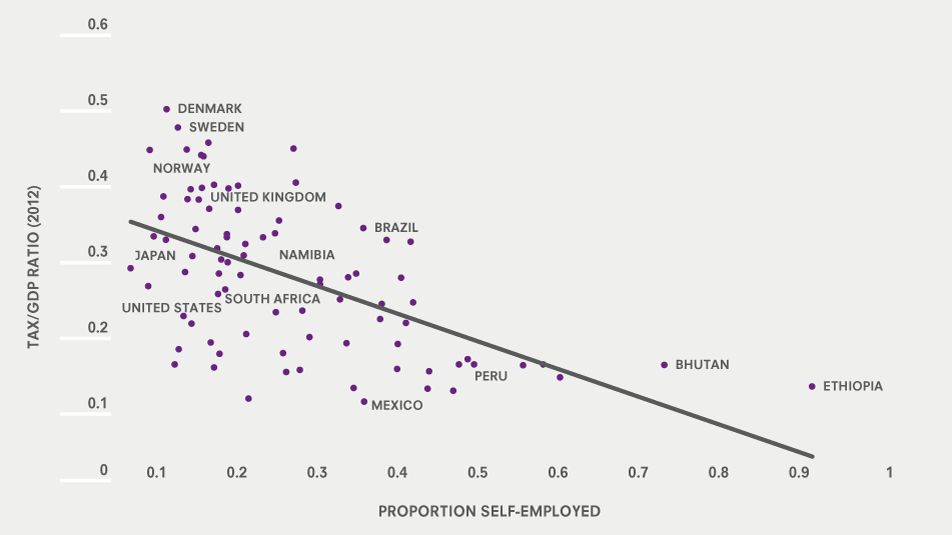

Figure 1: Tax collection relative to the proportion of self-employed workers

Source: Kleven 2014, adapted

Unwilling or unable to cheat? Evidence from Denmark

The impact of small informational barriers can be seen even in Denmark, which has an exceptionally effective tax enforcement system and the world’s highest tax-to-GDP ratio (48.6%). Evasion in Denmark is very low because most income is in fact third-party reported. In contrast, income in most low-income countries is purely self-reported. With the obvious caveat that Danish estimates do not directly apply to developing countries, we find that evasion rates on total income and on third-party reported income differ due to differences in enforcement. The results suggest that as the fraction of total income that is self-reported increases, evasion rates increase; whereas, the evasion rate for third-party reported income remains close to zero.

Specifically, as the fraction of income that is self-reported approaches 1 (similar to the situation in developing countries) our estimates indicate evasion rates could be as high as 50%. This is likely to be even higher in developing countries where self-reported income evasion is harder to detect (due in part to differences in availability of implicit third-party information trails such as credit cards). In other words, individuals are near-perfect compliers on third-party reported income, and at the same time, large evaders on self-reported income. Hence, tax enforcement is effective whenever third-party reporting is in place, but weak when it is not in place, even in an advanced economy like Denmark.

Source: Kleven, 2014

The structure and composition of labour markets in developing economies tends to be distinct from that of developed economies: developing economies have a higher proportion of self-employed workers (Kleven & Waseem, 2013; Kleven, 2014; Jensen 2016); smaller and less complex firm structures; and a less sophisticated financial sector. Many of these characteristics are interrelated and may partly explain why the scope for tax evasion tends to be greater in developing countries. The result, illustrated in Figure 1 opposite, is that countries where a higher share of the population is self-employed generate lower tax-to-GDP ratios.

The prevalence of these constraints in developing countries has meant that tax policies designed with the assumption of widespread coverage and availability of third-party reported information trails have proven highly ineffectual for tax revenue generation. The challenge for policymakers and researchers remains to develop a better understanding of how to design localised or contextually appropriate policies and systems for tax collection.

Image credit: Getty Images

As countries develop, both the proportion of tax revenues gathered from third-party reported sources and the tax-to-GDP ratio tends to increase. Increasing sophistication of financial systems and a shift towards more formalised employment may explain why tax compliance improves as countries become richer. Strikingly, in many cases, present-day tax-to-GDP ratios of developing countries are similar to the ratios of developed countries over a century ago.

Both developed and developing country tax systems collect some proportion of their tax revenues from self-reported information such as inheritance taxes, customs duties, excise taxes, or income from self-employment. As a result, all governments face similar enforcement barriers when collecting tax liabilities on self-reported income. Most developed or high-capacity governments use a range of mechanisms for enforcing tax payments on self-reported income such as implicit information trails, social pressures and tax morale.

Developing countries usually have higher percentages of self-employed workers and thus rely much more on self-reporting for income tax revenue generation. As self-reported income is easier to manipulate, tax evaders can report artificially lower earnings to reduce their tax liabilities, which is much harder to do for third-party verified income (Kleven & Waseem, 2013). The introduction of small informational barriers, even in developed countries, reduces the efficacy of tax enforcement systems and impairs revenue collection.

Countries where a greater proportion of the labour force is self-employed rely more heavily on taxing self-reported income. This, coupled with weaker enforcement capacity and fewer incentives for paying taxes, typically results in higher tax evasion rates in developing countries.

Key message 2 – Third-best policies, inefficient in developed countries, may prove efficient in developing countries

A ‘first-best’ approach to taxation assumes idealised conditions where governments face no barriers to information or enforcement. Under this approach, taxes are lump sum and based on an individual’s inherent ability or ‘type’.

As illustrated by the Danish case, even the most efficient systems face some informational barriers. Therefore developed countries have historically promoted ‘second-best’ approaches to improve the efficiency of tax collection in the face of information constraints. Commonly recommended policies include taxes on consumption, progressive income taxes, profit taxes, and value-added taxes (VAT) on goods and services.

Accepting that some informational barriers are inevitable, second-best policies aim to maximise social welfare with the instruments available, namely taxes on observable transactions (such as income and consumption) not ability. A central result in public economics is that secondbest approaches should promote production efficiency (Diamond-Mirrlees, 1971). Taxes on consumption, wages, and profits are encouraged while taxes on intermediate inputs, turnover, and trade are discouraged for distorting firms’ production decisions.

Optimal tax policies and instruments in developing countries may look very different to those in developed countries.

Both developed and developing countries use second-best taxes. However, the emphasis on production efficiency that characterises second-best policies ignores the constraints to enforcement and administration that face developing countries. In such cases, second-best approaches generate very low levels of revenue. Optimal tax policies and instruments in developing countries may look very different to those in developed countries.

In practice, tax structures of many developing countries incorporate policies that run counter to second-best approaches (Gordon and Li, 2009; Best et al., 2015). But in contexts with capacity constraints, such policies may prove better for revenue generation. For instance, where evasion on taxable profits is high, turnover taxes provide a broader and thus harder to evade tax base (Best et al., 2015). Production efficiency must be balanced against the need for revenue efficiency in developing countries.

Tax systems that account for differences in context and capacity in developing countries may produce very different policies. Where enforcement capacity and third-party verifiable financial transaction data is limited, policymakers should explore ‘third-best approaches’.

Let’s consider Minimum Tax Schemes (MTS), an example of a third-best policy commonly adopted by developing countries (Best et al., 2015). Here, firms are taxed either on profits or turnover, depending on which tax liability is larger.

Unlike profit taxes, turnover taxes cannot be evaded by over-reporting costs. In high evasion environments, turnover taxes may generate higher tax revenues than profit taxes.

One of the countries using MTS is Pakistan. A study conducted by IGC researchers in Pakistan demonstrates that turnover taxes could reduce evasion by up to 70% (Best et al., 2015). Gains to revenue efficiency from increased compliance significantly outweigh lost production efficiency. Rather than advocating that production-inefficient taxes be replaced by modern tax instruments, these results indicate that some production-inefficient taxes are better suited to countries with weaker enforcement capacities. Locally appropriate and optimal tax structures require a broader understanding of the trade-offs between production and revenue efficiencies.

Achieving higher tax revenues in developing countries is not simply a matter of increasing taxes – it requires careful consideration to identify optimal tax instruments. In developing countries, reforms to increase revenues must overcome barriers to collection and enforcement. Instruments must be flexible enough to adapt to changing public finance infrastructure and constraints.

Tax policy approaches: when third-best is best

Key message 3 – Harnessing social incentives may increase compliance

Standard tax compliance models focus on enforcement. They assume the main motivation citizens have to pay their taxes is the fear of being caught for non-payment or fraud. In developing countries, however, threats to catching tax evaders are much less credible. This raises the question of why citizens in developing countries pay taxes at all, given that the probability of being caught and punished for tax evasion is so low.

Citizens’ ‘tax morale’ – their personal willingness to pay taxes – may explain low compliance rates when enforcement is weak.

Bangladesh’s taxpayer recognition programme

The National Board of Revenue (NBR) in Bangladesh implemented several innovative programmes aimed at exploiting social incentives and peer-recognition to improve firm tax compliance. Collaborating with IGC researchers, NBR conducted a randomised field experiment to rigorously evaluate these programmes. In neighbourhoods where some firms were already tax compliant, the threat of exposing firms’ tax payment behaviour encouraged non-complying firms to start paying taxes. In neighbourhoods using social incentives, firms were up to 6 percentage points more likely to make VAT payments; total tax revenues paid increased by 17% (Chetty et al., 2014).

Universities and charities regularly leverage public interest and social recognition to generate funds (e.g. naming exhibits or buildings after donors). Similar approaches can work for tax collection. Exposing information about firms’ tax compliance to peers or the public – in effect shaming non-compliers and rewarding compliers – can alter firm behaviour. If recognition is cheap and firms find it valuable, such programmes may cost-effectively raise revenues.

Public finance research suggests that citizens’ ‘tax morale’ – their personal willingness to pay taxes – may explain low compliance when enforcement is weak. Tax morale is based on the idea that psychological factors such as intrinsic motivation or an individual’s civic mindedness, social norms, reciprocity, and cultural values of trust and belief in government all play a significant role in encouraging citizens to pay their taxes. These factors are detailed below:

- Intrinsic motivation. Citizens believe that paying taxes is the correct thing to do.

- Social norms. Citizens recognise that others in their social group pay taxes, and so fear being ostracised if they do not pay their own.

- Reciprocity. Citizens pay their taxes because they receive something in return from the government, such as social security support or public services (transport, education, healthcare, sanitation etc.).

- Culture. Cultural values (level of trust in government, political views, etc.) compel citizens to pay taxes.

Tax morale appears to be an important driver of citizens’ willingness to pay taxes, but rigorous evidence for how policymakers can raise intrinsic motivation and tax compliance remains relatively scarce. Further research and experimentation is needed to identify how to stimulate intrinsic motivation to comply with taxes, especially in settings with limited tax enforcement capacity. Emerging research focuses on whether linking taxes to service delivery outcomes could improve compliance. For instance, policies that provide incentives to pay taxes could boost tax morale, supplementing or substituting traditional approaches to improving compliance, such as penalties for evasion.

Key message 4 – Motivating tax collectors could bridge wider enforcement gaps

While the administration of public service delivery (e.g. healthcare and education) has been widely studied, tax administration has remained largely underexplored. Despite this, good administration is central to effective tax collection. In countries where tax morale and enforcement are weak, tax administrators may exert low effort and/ or be susceptible to corruption.

One of the key reasons for this is that, in many developing countries, incentives for civil servants are poor: pay is relatively low and not tied to performance, career advancement opportunities are limited or uncertain, and there is substantial scope for corruption or abuse of power. Yet the effectiveness of tax systems depends substantially on the motivation of the tax staff responsible for providing public services.

Low motivation among tax collectors contributes to low tax collection and reduced funding for public services, which in turn undermines tax morale. Citizens that fail to receive adequate public services see no reciprocal benefits to paying their taxes. This creates a vicious cycle that inhibits economic growth.

Providing performance-based incentives to tax collectors produced substantial increases in revenue collection.

To address this problem, the Excise and Taxation Department of the Punjab province in Pakistan tested several innovative schemes focused on improving tax collector performance as part of a multi-year collaboration with IGC researchers.

The goal was to increase revenues for government by incentivising tax collectors to bring in more taxes without over-taxing citizens. The study finds that providing performance-based incentives to tax collectors produced substantial increases in revenue collection. Treatment areas where incentives were introduced outperformed control areas by a margin of over 13 percentage points in total revenue collections over the two-year study period. Importantly, the increase in revenue more than paid for the cost of the incentive reward scheme.

The study also found that more transparent, simpler schemes work best, such as explicitly linking incentives to clearly defined performance measures that leave limited room for subjectivity. However, the research also found that in cases where collusion is possible, performance-based pay can lead to undesirable outcomes by enhancing the tax collectors’ bargaining power to extract side payments. In such cases, complementary efforts are needed to raise the costs of collusion and increase the perceived returns to paying taxes.

Strengthening tax administration is crucial for improving the government’s ability to enforce its tax policies and collect revenues. New research is testing the effectiveness of offering non-financial incentives to tax collectors, including transfers to more desirable posting locations as a reward for strong performance.

Policy recommendations

Effective tax enforcement is central to a government’s ability to fund infrastructure and public service delivery. Ineffectual tax policies contribute to higher levels of corruption, evasion, and ineffective political structures. Barriers to effective tax collection, enforcement, morale and administration all constrain the fiscal capacity of developing country governments to finance the expenditures on services and infrastructure needed to spur growth. Public finance reform is, however, only one piece of a larger growth puzzle. For increased tax revenues to translate into meaningful and transformative growth, broader reforms to procurement and public sector practices are needed alongside improvements in accountability and transparency.

Characterised by higher informality and selfreported income, developing countries often lack the enforcement capacity needed to effectively wield modern tax instruments. Modern tax systems require third-party verifiable information trails generated through widespread monitoring and reporting of financial flows. Without this, evasion increases and revenues decrease.

Historically recommended reforms centred on secondbest approaches, champion production efficiency above all else. These ignore the enforcement challenges experienced by most developing countries. A new wave of third-best policies, prioritising revenue efficiency, illustrate that higher revenues, generated by tax policies accounting for capacity constraints, may outweigh lost production efficiency.

This brief provides four key recommendations for policymakers striving to increase tax revenues:

- Strategies for increasing tax revenues must account for a country’s local context and its particular constraints. Developing countries tend to have weaker tax collection and enforcement systems; even incremental improvements could increase much-needed revenues.

- Policies for developing country governments may need to shift away from production efficiency in favour of revenue efficiency. Policy design must account for higher tax evasion rates and invest in third-party reporting systems.

- Leveraging incentives and social pressures on taxpayers could improve tax compliance. Social recognition schemes show promise in raising tax compliance. However, better evidence is needed to understand how to harness citizen tax morale.

- Incentives to improve tax administration are vital in addressing challenges to tax enforcement. Implementing simple and objective performance-based pay schemes can incentivise tax collectors in developing countries, offering an escape from cycles of low pay, low motivation, and low productivity. Incentives must be balanced against abusive over-taxation.

References

Andreoni, J., Erard, B., & Feinstein, J. (1998). Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature, 818–860.

Atkinson, A. B., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1976). The design of tax structure: Direct versus indirect taxation. Journal of Public Economics, 6(1), 55–75.

Auriol, E., & Warlters, M. (2005). Taxation base in developing countries. Journal of Public Economics, 89(4), 625–646.

Best, M., Brocmeyer, A., Kleven, H., Spinnewijin, J., Waseem, M. (2015). Production vs Revenue Efficiency With Limited Tax Capacity: Theory and Evidence From Pakistan. Journal of Political Economy, 123(6), 1311–1355.

Besley, T. J., & Persson, T. (2013). Taxation and development. Handbook of Economic Development.

Chetty, R., Mobarak M., & Singhal, M. (2014). ‘Increasing Tax Compliance through Social Recognition.’ IGC Policy Brief.

Diamond, P. A., & Mirrlees, J. A. (1971). Optimal taxation and public production II: Tax rules. The American Economic Review, 261–278.

Gordon, R., & Li, W. (2009). Tax structures in developing countries: Many puzzles and a possible explanation. Journal of public Economics, 93(7), 855–866.

Jensen, A. (2016). Employment Structure and the Rise of the Modern Tax system. Job market paper.

Khan, A. Q., Khwaja, A. I., & Olken, B. A. Tax farming redux: Experimental evidence on performance pay for tax collectors. Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

Kleven, H. J. (2014). How can Scandinavians tax so much? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 77–98.

Kleven, H., Best, M., Brockmeyer A., Spinnewijn, J., & Waseem, M. (2015). Production vs Revenue Efficiency with Limited Tax Capacity: Theory and Evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Political Economy, 123(6).

Kleven, H. J., Knudsen, M. B., Kreiner, C. T., Pedersen, S., & Saez, E. (2011). Unwilling or unable to cheat? Evidence from a tax audit experiment in Denmark. Econometrica, 79(3), 651–692.

Kleven, H. J., Kreiner, C. T., & Saez, E. (2015). Why can modern governments tax so much? An agency model of firms as fiscal intermediaries. Econometrica,forthcoming.

Kleven, H. J., & Waseem, M. (2013). Using notches to uncover optimization frictions and structural elasticities: Theory and evidence from Pakistan. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2), 669–723.

Luttmer, E., & Singhal, M. (2014). Tax Morale. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4), 149–168. The Economist (2014). Future of Banking in Africa. Economist Insights. Accessed 10 February 2015: www.economistinsights.com/financial-services/event/future-banking-africa-2014.

Citation

Kleven, H., Khan, A., & Kaul, U. (2016). Taxing to develop: When ‘third-best’ is best. IGC Growth Brief Series 005. London.