How can policy address growing public/private transport needs?

Introduction

Cities drive growth because of their ability to bring together firms and workers in a way that allows for large scale and specialised production. With a large pool of connected individuals, people can specialise in particular tasks and be matched to jobs that are most suited to them, and firms can specialise to meet the specific demands of consumers.

Urban mobility is at the heart of this process, fundamentally determining a city’s potential for productivity and liveability. Unless people and products can move efficiently across the city, firms get locked into small-scale unproductive activities, and people cannot access basic goods and services. This is the case in many developing cities, where non-existent walkways, crippling traffic jams and weak public transport systems undermine the city’s connectivity.

Policymakers in these contexts face difficult trade-offs in improving systems of mobility, both in addressing growing demands for private transport, and in investing in public transport links in a city. Learning from the experiences of cities across the globe facing these challenges offers some key lessons for enhancing mobility in cities; by complementing investments in infrastructure with smart regulation, cities such as Singapore and Lagos have been able to meet growing demands for transport. Not only do these investments help to overcome the potential downsides of density – they can kick off a development process by credibly signalling to investors of where future economic activity will cluster.

Key messages

- Building roads is not enough. Though investment in road infrastructure is vital in expanding access in a city, this comes at a high cost and is unlikely to solve the problem of congestion in developing cities. Evidence from US cities suggests that as incomes and populations rise, vehicle use will rise to fill new roads. Infrastructure needs to be met with regulations on private cars and investment in public transit.

- Existing informal transport is a complement, not a substitute, for higher capacity systems. In many developing cities, informal minibuses and motorbikes form the backbone of public transport. Even as governments invest in higher capacity transport modes, these systems will continue to provide essential feeder services from low density areas. Regulation can improve the quality of these services but this can come at the cost of affordability or quantity.

- In many cases, bus rapid transit systems can alleviate congestion problems at a fraction of the cost of rail based systems. Rail based systems have significant advantages in terms of their relative limited land use and environmental sustainability – but it is only at very high levels of urban density that investing in light rail or mass rapid metro rail may make sense in terms of overall cost effectiveness.

- Link transport investments with land use in a city. Urban density is a crucial determinant both of the desirability and financial sustainability of higher capacity transport systems. Linking transport systems with land use and land use planning can massively enhance the benefits of investing in connectivity.

An extended Cities that Work synthesis paper on urban mobility is available here.

Is investing in infrastructure enough?

In many developing cities, travel by car, motorbike, bicycle or by foot are the main means of transport in a city. Meeting growing demand for these private means of transport requires investing in building and maintaining infrastructure for private transport. The density of paved roads, for example, in countries in sub-Saharan Africa is less than a quarter of that in other low-income countries1. Without addressing these deficits, access to opportunities across a city are limited. Initial results from a study of 154 cities in India suggest that around 70% of differences in car speeds in a city are the result not of traffic, but of the extent and organisation of road infrastructure2.

Initial results from a study of 154 cities in India suggest that around 70% of differences in car speeds in a city are the result not of traffic, but of the extent and organisation of road infrastructure.

Infrastructure for non-motorised forms of transport in particular offer low-emission, low cost access across shorter distances and in dense central areas of cities can offer the quickest form of travel. Non-motorised infrastructure also comes at relatively low costs; estimates suggest that a pedestrian walkway that can accommodate 4,500 people/hour/direction costs approximately USD$100,000/kilometer. This is up to 50 times less costly than an urban road that can carry only 800 people per hour per direction3.

However, investing in infrastructure for private transport is not going to be sufficient to meet growing demand:

- Private cars have low carrying capacity, and so without investing in higher capacity transport options, roads are less able to transport high volumes of passengers.

- Investments in roads take time and come at a significant cost. The average cost of constructing a two-lane concrete highway across developing countries is approximately $1.5 million per kilometre4.

- Evidence from US cities suggests that there is a fundamental law of highway traffic: expanding roads, although allowing for greater ease and access of transport for many citizens, will not solve a city’s congestion problem. This is because as incomes and populations rise, vehicle use will rise to fill these new roads5. In Accra, for example, despite relatively good roads, traffic congestion continues to rise as around 2 million commuters travel to the downtown central business district each day. This problem is only likely to grow as the population of Greater Accra is predicted to double by 2035, along with private vehicle use.

What kind of regulations on private vehicles are best suited to a city in reducing congestion?

As such, policy is needed to manage demand for private transport. There are two ways in which policymakers can incentivise citizens to switch to public transport use:

- Putting an additional price on private transport. This can be done by imposing a quota on car ownership and allowing users to bid over user-rights, as seen in Singapore. This can also be done through congestion charges and parking fees that impose an additional private cost on driving.

- Quantity restrictions on vehicle ownership or usage. This can include vehicle license restrictions, high occupancy vehicle restrictions that regulate the number of people in a car, and ‘odd-even’ policies that only permit certain vehicles to use roads on particular days.

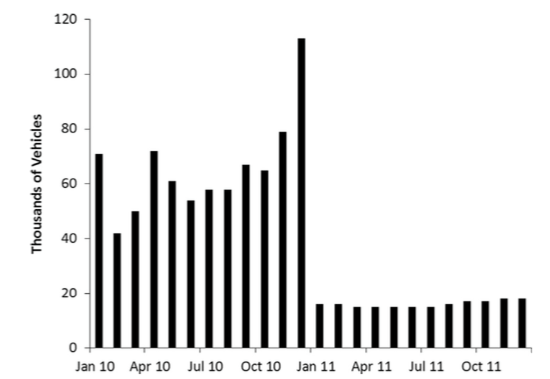

Monthly changes in new vehicle registration in Beijing, 2010 – 2011.

Since 2011, vehicle licence plates in Beijing have been restricted and allocated to drivers based on a public lottery. (Source: Yang et al., 2014)

Though both types of restrictions have proved effective at limiting congestion across cities, financial restrictions are advantageous in three main ways. By allowing an open market to determine who is willing to pay to use their vehicles, user-rights are efficiently allocated to those who are most willing to pay. Financial disincentives also raise revenues for governments, enabling a win-winsituation where restrictions on private use can be used to fund public transportation systems. The revenues from private vehicle auctioning in Shanghai, for example, were approximately USD$700 million in 2011 – roughly enough to cover the cost of all public subsidies for public transport systems in 20126. At the same time, quantity restrictions that limit the use, rather than the ownership, of cars, have in many cities had limited long term effects on overall vehicle use and congestion in cities. In Mexico City, for example, the introduction of an odd-even restriction on cars actually increased vehicle emissions in the city 7.

The revenues from private vehicle auctioning in Shanghai, for example, were approximately USD$700 million in 2011 – roughly enough to cover the cost of all public subsidies for public transport systems in 2012

While congestion pricing systems in London or Stockholm involve costly and complex technology to track and fine car usage, this doesn’t have to be the case. In Singapore in 1975, a low-cost paper license system was introduced to restrict car usage in the downtown area during rush hour. Colour coded tickets made enforcement of this system easy to implement. Financial restrictions may be seen as overly burdensome on poorer section of society – but it is important to note that in practice, more wealthy households are also able to overcome quantity restrictions such as odd-even policies by buying additional cars.

How can policymakers improve compliance with private vehicle regulations?

Restrictions on private vehicles are extremely difficult to implement, given resistance from existing users. Across both developed and developing cities, these regulations have had limited traction. But successful reforms across developed and developing reveal some key principles for enforceable regulation:

- Public consultation and awareness campaigns. Before the congestion charge scheme was introduced in London in 2003, for example, the Mayor invited feedback on proposed legalisation from a wide range of stakeholders, in particular those citizens who were most likely to have their journeys and residential areas affected. Based on feedback received, modifications were made which allowed for greater public ownership and acceptance of the scheme8. Awareness campaigns can help to inform the public of the social benefits of regulations in terms that reduce traffic in the city.

- Investment in expanding and improving public transport alternatives. These investments are needed to assure means of mobility for those otherwise restricted. Attempts to ban motorbikes to improve safety in Kigali, Rwanda in 2006, for example, without adequate affordable alternatives for mass transportation, have been met with strong political resistance. In Oslo, resistance to the introduction of a toll charge in 1990 was overcome by use 20% of revenues from toll charges for public transport investment.

- Incremental expansion of policies. If people are able to experience the benefits of private vehicle regulation through reduced congestion (and improved public transport services as a result), they are more likely to support the expansion of regulations. Singapore introduced the principle of congestion pricing in the 1970s through a very simple paper-based system when income levels in the country were comparable to many African countries. Over time, the city has gradually upgraded this into a state-of-the-art electronic pricing system. Introducing the principle of a congestion charge early enables people to understand that they need to pay for the social costs of car usage, making future reforms much easier.

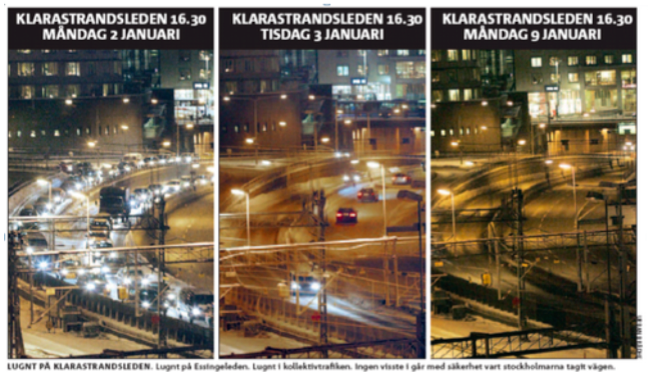

Congestion pricing in Stockholm, Sweden

In 2006, Stockholm introduced a seven-month trial congestion charge in the inner city that reduced traffic volumes by approximately 22%, resulting in significant reductions in congestion and travel time9. Significant investments at the national level in technology to enforce the charge were accompanied by communication drives that clearly linked congestion charge payments to the benefits they brought.

Stockholm’s roads before and after the congestion trial. Extensive mass media was used to highlight the effects of the charge on congestion.

Following this trial, a public referendum was held to determine whether the scheme would be introduced permanently. 53% of Stockholm’s citizens voted in favour of the charge. By incrementally introducing the charge, citizens could see the benefits of the charge for themselves before deciding on whether they supported this policy change. Public participation in a referendum ensured that whatever the outcome, it would be politically acceptable. As a result, the congestion charge was permanently introduced in 2007 – with similar continued reductions in traffic volumes as a result.

Working with informal transport

In many developing cities, access to high capacity public transport services is severely limited. Whilst growing use of private vehicles reduces the profitability of high capacity services, limited public investment in mass transit means that the quantity and quality of these services remains low. At the same time, regulations to control public transport vehicle licenses and route operations often limit profitability of formal provision. In this context, informal medium- or low-capacity vehicles form the predominant means of transport in developing cities. In Dakar, for example, informal minibuses are responsible for meeting over 80% of transport demands in the city. How governments approach these systems can play a decisive role in the productivity and liveability of cities.

Informal does not mean unorganised; there is tremendous variation in the scale and organisation of these services in developing cities. But what differentiates them from formal public transport is that they lack some of the necessary permits for operating legally. Limited enforcement of regulations means these services can fill the gap left by inadequate formal public transport.

Do existing informal transport systems help or hinder mobility in developing cities?

These informal transport systems provide essential means of mobility in developing cities. In addition to being a significant source of employment in many of these cities, such services can often offer better and more reliable services than existing formal transport systems. Because of their relatively smaller size when compared to high capacity buses, minibuses, taxis and motorbikes are relatively cheap to invest in; a 14-seater minibus in Nairobi, for example, costs almost 4 times less than a 35-seater bus10. These lower costs mean private operators can profitably supply these services in greater quantity and at lower fares. These vehicles can also travel almost anywhere where (even low quality) roads exist, and as such, are likely to be able to get commuters closer to their destinations.

However, these systems also come with their costs. In an effort to cut costs and improve profitability in highly competitive markets, informal vehicles are often poorly maintained, overcrowded and unsafe. Reckless driving means that in cities such as Douala, two-thirds of moto-taxi drivers have been victims of traffic accidents11. At the same time, as these vehicles are at best medium-capacity, large numbers of vehicles are required to provide mass transport. This, combined with their irregular stops, mean that these vehicles contribute significantly to traffic congestion in city centres. As passenger volumes rise above around 5,000 in each direction per hour, high capacity buses can become more cost effective when accounting for commuters’ time otherwise wasted in waiting for transport12.

Can regulation of informal services improve urban mobility?

In thinking about implementing effective regulations to improve existing informal transport services, it is important to distinguish between those that seek to improve the quality of these services, and those that seek to restrict their supply in particular areas:

- Regulation to improve the quality of these services and cap fares can be beneficial for commuters using them – but this is by no means guaranteed. Any attempt to improve quality of services is liable to come at the cost of affordability, and any attempt to reduce fares is liable to be met with a deterioration in the quantity or quality of services.

- Regulation to restrict the supply of these medium-capacity services on particular lanes in an effort to reduce congestion and improve financial sustainability of higher capacity buses can have significant public benefits in highly congested city centres. However, this is likely to face strong resistance from existing providers. At the same time, more expensive high-capacity buses are less appropriate for low-density, low-income areas that will not generate sufficient demand to cover costs of provision. Without subsidies on higher capacity transport modes, this is likely to increase transport expenses or travel time for commuters.

Any attempts at effective regulation rely on adequate enforcement capacity. Regulating informal transport, particularly when done in an effort to accommodate higher capacity transport modes, can be extremely difficult to implement due to strong resistance from existing operators. In many developing cities, however, this capacity to effectively monitor regulations is weak. In these cases, overly ambitious regulations that exceed capacity and undermine the rule of law can actually be more damaging than having no regulations at all.

Overcoming resistance to regulation

Successful experiences from a number of cities suggest that in many cases, the best way for governments to improve public transport services is to work with informal providers to combine regulation with finance, or access to private finance, to maintain and improve vehicles. For example, expanding access to new vehicles, credit and training to collectives of informal private operators in Dakar, Senegal, has allowed for renovation and route regulation of around a fifth of minibuses in the city between 2005-200813. In Lagos and Accra, governments provided the finance or financial guarantees that allowed existing informal vehicle owners to form cooperatives and jointly invest in higher capacity buses. To ensure these high capacity buses were financially sustainable, financial support was combined with regulation to enforce exclusive use of particular routes. Public transport needs were met and congestion was reduced while maintaining crucial political support for the introduction of higher capacity buses. Lower capacity services then complemented formal transport services by providing feeder services from low density areas to higher capacity systems in denser areas.

Discussion and compromise with existing operators is key to limiting resistance to the introduction of high capacity systems to replace existing vehicles. This crucially includes providing employment opportunities in new systems; in Johannesburg, for example, minibus taxi operators were included in negotiations on the new bus rapid transport (BRT) from the start, allowing them to become drivers and shareholders in the new system and limiting resistance14.

… in many cases, the best way for governments to improve public transport services is to work with informal providers to combine regulation with finance, or access to private finance, to maintain and improve vehicles.

Investing in higher capacity transport

In high density areas of a city where large numbers of commuters need to get to and from, investing in higher capacity transport systems plays a vital role in reducing congestion. Broadly speaking, there are four types of higher capacity transport system:

- High-capacity buses

- Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems where buses have priority or sole use on dedicated lanes

- Light Rail Transit (LRT) systems where trains run over-ground on an exclusive-dedicated line. This is distinct from tram systems which operate on roads.

- Metro or mass rapid transit (MRT) systems where high-capacity trains travel either above or underneath the ground.

BRT or LRT?

Due to the limited impact of buses on already congested lanes, and the prohibitive cost of metro systems, policymakers often face a choice between investing in BRT or LRT systems.

Transjakarta BRT system in Jakarta

Addis Ababa’s Light Rail system

These systems have a wide range of carrying capacities and costs. BRT systems can range from being able to transport around 2,500 people/hour/lane to over 20,000 passengers/hour/lane in more sophisticated systems such as Bogota’s high capacity TransMilenio BRT15. LRT systems can have higher capacities but generally fall somewhere in this range. The two-line 34km LRT system opened in Addis Ababa in 2015, for example, is estimated to have a carrying capacity of 15,000 passengers/hour/line16.

LRT systems are generally more expensive to construct and operate for the same carrying capacity. For example, in Lagos, the 22km BRT system cost just USD$1.7 million per kilometer to build, including the cost of stations, road partitions and 220 buses17. This works out to less than 2 million per kilometer – over 8 times cheaper per kilometer and per passenger than the LRT system in Addis Ababa.

LRT systems are generally more expensive to construct and operate for the same carrying capacity.

Economic analysis suggests that BRTs are likely to be the most cost-effective option in terms of capital, operating and delay costs18. This only changes in very high-density areas where hourly passenger volumes are in excess of 30,000, where a bus-based system could result in significant and costly delays. The higher construction and operation costs associated with rail-based systems, as well as the likely need for higher public subsidies, may instead be justified on the basis of other benefits, including environmental sustainability and relative land requirements.

The importance of urban density

One vital factor that can help in determining appropriate investments for a city is levels of urban density. The higher the urban density, more people who benefit from a given station being built – and relatedly, the lower the cost per person of connecting people to the system. This means that the costs of building and operating these transport systems can be more easily recouped from users through fares. Urban density is therefore a crucial determinant of financial viability. It is estimated that BRT systems, for example, can only remain financially viable if there are at least 10 passengers boarding per kilometer per day per bus19.

It is important to note that because of the significant public benefits of public transport services, governments should not necessarily expect them to recover costs purely through fares. An additional source of revenues could be the urban land value appreciation created by the transport project; Hong Kong, for example, was able to finance its entire mass rapid transit system by selling off high-value retail spaces created in properties built on top of stations.

Furthermore, in many cases, subsidies on high capacity transport implemented in an effort to reduce congestion can allow for a positive cycle of financial sustainability. With higher investment, better and more frequent public services are provided. This can increase ridership which in turn increases revenues from fares.

As they grow, cities can incrementally develop transport systems appropriate to rising density. With very high levels of urban density, it can become necessary to invest in even higher capacity mass rapid metro systems, with trains that run over- or underground in a city. These systems, such as the New York City subway and the Shanghai Metro, have much higher carrying capacities and significantly higher costs.

The role of land use planning

The importance of urban density in improving the financial sustainability of transport systems highlights a key role for urban land use planning to encourage density around transport routes and terminals.

Land use to complement transport investments in Curitiba, Brazil

In Curitiba, Brazil, complementary reforms to land use planning alongside transport investments have ensured financial viability and popularity of their BRT system, implemented in 1974. This has been achieved in two main ways 20:

- Land use regulation to encourage transport orientated development – higher density in areas surrounding BRT lines and major roads. On sites along the planned transport axes, legislation permits buildings with total floor sizes of up to six times the total plot size, with density of development decreasing with distance from public transport links. In this way, the city has been able to ensure linkages between residential and commercial density and the transport requirements that come with such density.

- Land use planning actively encouraged use of public transport by providing pedestrianised access to public transport in the city centre, as well as dedicated land space allocated to exclusive bus lanes.

By complementing land use and mobility investments, the costs charged per passenger have been able to be maintained at affordable rates: citizens pay only approximately 10 percent of income on travel 21. As a result of improving convenience, affordability and proximity of this system, by 1991 it was estimated that 28% of commuters has switched from car to BRT travel 22.