Moving from a fixed to a floating exchange rate: The case of the South Sudanese Pound

The Government’s decision to peg its new currency, the South Sudan Pound (SSP) to the US dollar, was largely intended to protect against oil price volatility. Amidst falling oil prices and the outbreak of civil war, the Government rapidly depleted its USD reserves and spurred the emergence of a currency black market. This blog argues that the decision taken to float the exchange rate, by the Bank of South Sudan and the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning on 14th December 2015, was the best option to avoid collapse of the SSP and the dollarisation of the economy.

Shortly after South Sudan became an independent country on 9 July 2011, it adopted a new currency: the South Sudan Pound (SSP) which, like it’s predecessor, (the Sudanese pound) was maintained at a fixed exchange rate. Over 90% of the Government’s revenues come from oil exports, a fixed exchange rate provides a buffer to the domestic economy against volatile oil prices and protects against the risks of Dutch Disease that befall many mineral exporting economies.

As revenues from oil dry-up, a currency black market emerges

The Sudanese Pound was fixed at a rate of 2.96 to the US Dollar (USD), and the SSP has been pegged at the same rate. Maintaining a fixed peg requires sufficient foreign exchange reserves to back the exchange rate. At independence this was not much of an issue, as the country had more than 2 billion USD in reserves, oil production was flowing, and oil prices were still relatively high.

In January 2012, a dispute over unpaid transit fees with Sudan led South Sudan to shut down oil production. With halted oil exports, South Sudan’s main source of revenue fell very quickly. As the demand for dollars began outstripping the available supply at the official rate, it led to the emergence of a parallel black market.

Initially, the divergence between the official and the parallel rate was relatively small, with the parallel rate hovering around 4 SSP to the USD. However, the situation deteriorated as in December 2013 a civil war broke out in South Sudan. This led to large increases in spending, particularly on defence. It also led to renewed shut downs of some of the oil fields as these were in areas of some of the strongest fighting. As Government spending ramped up, its main source of revenue dried up. This was further compounded by a fall in world oil prices.

Reserves depleted, the Bank of South Sudan began printing more SSP to finance deficits

By October 2015, the Government was only able to fund about a third of its spending from revenues. To fund the growing deficit, the Government of South Sudan drew initially on accumulated reserves. Reserves were rapidly depleted from a position of over 2 billion USD at independence to less than 60 million USD by October 2015. The reserves left would be insufficient to cover even one week’s worth of imports.

The Government then started borrowing from the Bank of South Sudan, which began printing SSP to meet the demand. The additional influx of nearly 600 million SSP per month into the economy started to severely affect the exchange rate, the money supply and inflation.

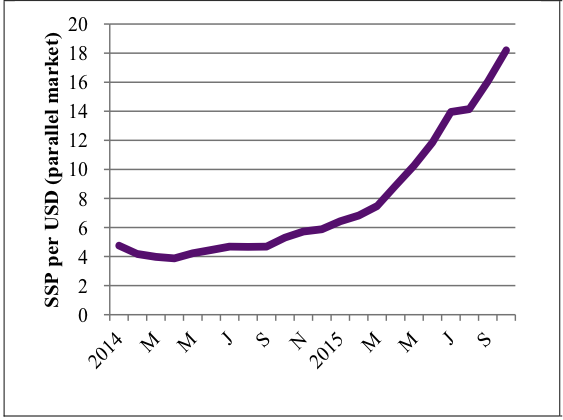

Figure 1: Parallel market exchange rate

As the Government continued to maintain the fixed official rate, the effect was seen in the parallel market, illustrated above in Figure 1. Since January 2015, there has been a rapid depreciation of the SSP relative to the USD by over 65%. Now the rate is changing almost on a daily basis and is currently between 17 to 18 SSP to the USD.

To fund the growing deficit, the Government of South Sudan drew initially on accumulated reserves. Reserves were rapidly depleted from a position of over 2 billion USD at independence to less than 60 million USD by October 2015.

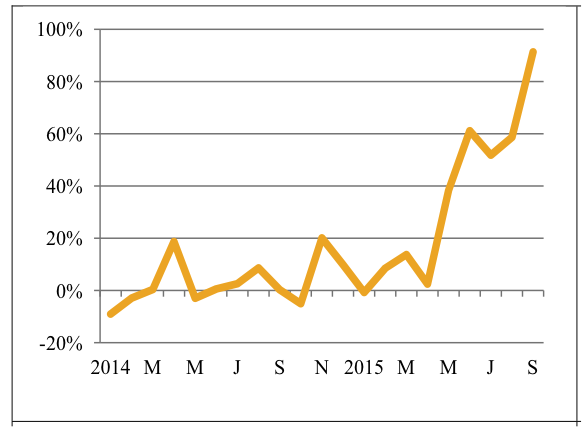

This in turn is driving inflation, which, as illustrated in the figure below reached over 80% in October 2015.

Figure 2: Inflation rates jumps as monetary supply expands and the parallel exchange rate depreciates

A fixed official rate, coupled with growing demand for USD, pushes up black market rates

As the official rate remains at 2.96 SSP to the USD, one of the most profitable activities in the economy is currently “round-tripping”, i.e. a few privileged individuals, who can, purchase USD at the official rate and sell them on the black market at a much higher rate. This is not only an unproductive activity that generates no value for the economy, it also means that the individuals receiving USD are crowding out allocations of USD to other private sector entities needing to import goods as well as commercial banks.

The exchange rate is arguably the most important price for an open economy. Therefore, if the issue is not resolved, then South Sudan risks heading in the same direction as Zimbabwe in 2008, when hyperinflation resulted in the eventual dollarisation of the economy and complete collapse of the domestic currency. In order to avoid this, there are various measures that South Sudan can implement, with a view to unifying its exchange rate and moving to a floating exchange rate regime (as outlined in this paper):

- Allow commercial banks to buy and sell foreign exchange at whatever price they want. This will formalise the parallel market, bringing it off the street and into the commercial banking system.

- Reduce and eventually stop allocations of foreign exchange at the official rate, thereby phasing out the official exchange rate.

- Develop and implement a credible plan to reduce fiscal spending. Any exchange rate reform will only work if the government reduces its fiscal deficit.

- Move from a fixed to a floating exchange rate. Although there are disadvantages associated with floating exchange rates, the Government currently has no reserves with which to manage any other regime and therefore this remains the only available option.

Epilogue: A freely floating exchange rate for the SSP is a major economic development

On December 14th 2015, the Bank of South Sudan and the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning announced that the SSP would become a freely floating currency. Although this will eliminate many of the current challenges, it will still require major adjustments by all participants. Implementing such reforms in the near future will prove timely.

...one of the most profitable activities in the economy is currently “round-tripping”, i.e. a few privileged individuals, who can, purchase USD at the official rate and sell them on the black market at a much higher rate.

The Peace agreement to end the civil war, currently being implemented, will help to build political credibility. Economic reforms recommended herein and now initiated by the move to a freely floating currency, will complement efforts by strengthening South Sudan’s economic credibility. The peace agreement may also lead to additional foreign exchange inflows, from Development Partners, and from the re-opening of oil wells that have been closed due to the war. This will help to protect any floating rate on the downside, and reduce the risks of further depreciation.