Making the Green Revolution greener: Agricultural adaptation and climate change

Climate change poses a striking threat to the livelihoods of rural farmers in low-income countries. As weather patterns become more volatile, agriculture will be disrupted, worsening food security and poverty. In response, farmers will be forced to adapt. Increasing agricultural productivity and introducing climate-resilient practices through technology can support incomes whilst encouraging structural transformation into manufacturing or services. However, technological adoption is already a challenge in many low-income countries, prevented by a host of market inefficiencies. These need to be understood and overcome if there is going to be a fourth agricultural revolution – one that meets the demands of poverty reduction and climate change.

Agriculture is the basis of livelihoods for millions. In many low-income countries, there is often two-thirds of the workforce working in agriculture, contributing around one-third of GDP. Most of this is subsistence agriculture, where farms are small in scale and barely mechanised. Farmers and their plots act as a key conduit of food security, sustaining families and networks in rural communities. Despite their low productivity, they are hugely important to national economies and livelihoods.

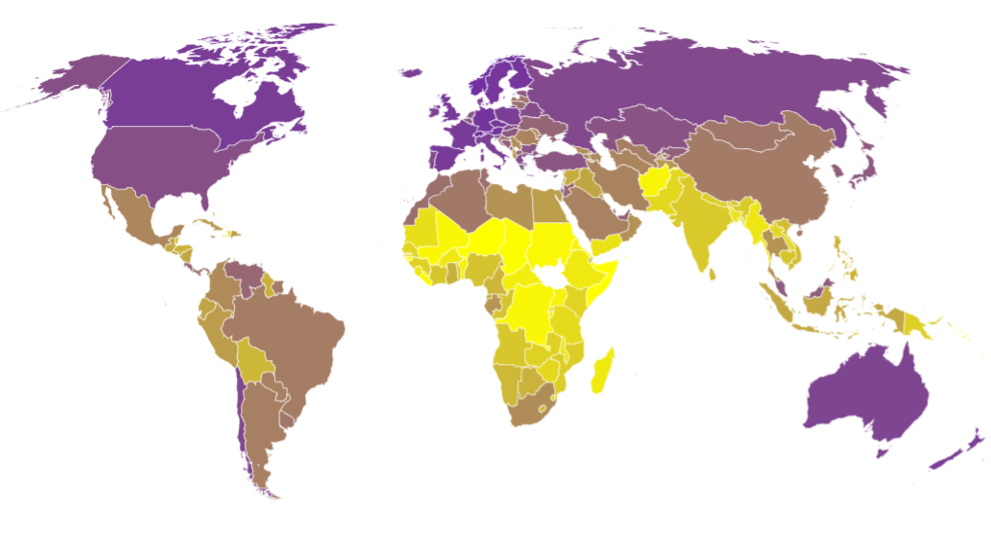

In turn, agriculture is intrinsically tied to the natural environment. Successful harvests rely on consistent weather patterns, which climate change is dismissing through more extreme weather events. Locust swarms, cultivated by more frequent cyclones and warmer temperatures, are destroying crops. Droughts, floods, and wildfires are becoming more commonplace. Largely owing to geography, increasingly unstable weather patterns will disproportionately affect low-income countries (Figure 1). Rural farmers will find themselves at the top of the list of recipients of the new climate precarity. Left unchecked, this disruption could devastate livelihoods, worsen food security and poverty, and potentially force mass channels of migration.

Figure 1: Developing countries are most vulnerable to climate change

Data source: Climate Change Vulnerability Index, ND-GAIN

Data source: Climate Change Vulnerability Index, ND-GAIN

In the face of climate risk, agricultural practices will need to be adapted and transformed. This is not an entirely new topic. Using technology to improve agricultural productivity has become a renewed focus for development economists and policymakers in the past few decades. It is seen as a potentially strong driver towards industrialisation, whereby workers will move into higher productivity sectors such as manufacturing or services. This will raise incomes and lower poverty, as well as help lower the number of workers who are exposed to climate change through the agricultural sector. On top of higher productivity, the right technologies can build climate resilience, helping farmers to cope better with the inevitable weather shocks. Overall, agricultural adaptation through technological adoption presents an attractive double opportunity to foster both economic development and climate change resilience.

Green Revolution

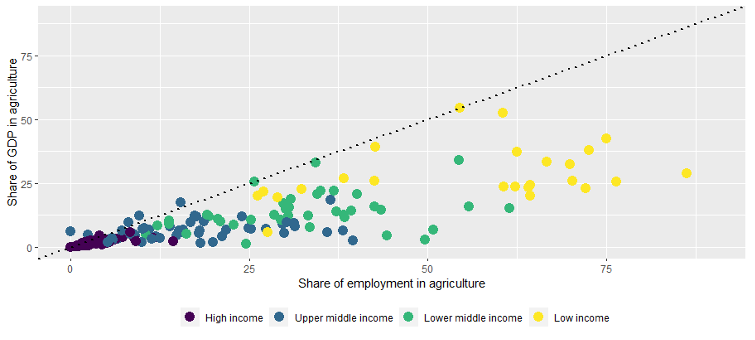

In the mid-20th century, the Green Revolution, or the Third Agricultural Revolution, led to the increase of agricultural production worldwide. It involved the adoption of new technologies including high-yielding crop varieties, fertilisers, insecticides and pesticides, and irrigation. It led to quick and vast improvements in agricultural productivity in Latin America and Asia. However, in sub-Saharan Africa, there was and remains a distinct lack of adoption, resulting in lower fertiliser use and agricultural yields. In lower income settings in general, farms are characterised by their small-scale and low productivity, leading to lower output per worker in agriculture compared to higher income settings (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Low productivity in agriculture means lower output per worker (countries by income)

Data Source: World Bank (2021) World Development Indicators

The reasons behind this lack of adoption are varied. A useful framework centres around a number of market inefficiencies. Some technologies may simply not be adopted because they are not beneficial in certain settings, such as those designed to be profitable for richer farmers. Examples of market inefficiencies that may prevent adoption include farmers unable to access credit, problems with infrastructure and supply chains, and perceptions around the riskiness of investments, all of which are often more pronounced in low-income settings. Research and field experiments are key to understanding how they can be overcome to improve productivity and incomes. This is critical because, without overcoming these inefficiencies, it will make the adoption of climate-resilient technologies much more difficult.

Harnessing the wind

The interaction between climate change adaptation and technological adoption is already observable in lower income settings. In Ethiopia, research found climate change to be affecting farmers’ decisions on land and labour contracts, which in turn influenced the probability of technological adoption and agricultural productivity. In Zambia, subsidies were found to be successful in overcoming market inefficiencies and incentivising technological adoption, which also served to improve environmentally-friendly land use for several years after. On the other hand, in India, where worsening water scarcity was leading to lower incomes, farmers were unable to adapt their agricultural practices and forced to find non-farm employment, with more success in areas that had a larger manufacturing sector.

These examples portray a more optimistic future of what agriculture adaptation in low-income settings could look like. Smart public policy needs to be geared to increasing productivity and climate resilience within agriculture, alongside the creation of decent employment in other sectors. This success will be critical to creating a fourth agricultural revolution; one which sees widespread adoption of climate-resilient and productivity-enhancing technologies together.

Adaptation and growth together

Agricultural adaptation is positioned at the nexus between climate change and poverty reduction, two of the greatest policy challenges of the 21st century. Greater exposure to the effects of climate change will bring the problems directly to the doors of the most vulnerable, necessitating an innovative and extensive response to support livelihoods. Solutions will be found in understanding how technology can be adopted in agriculture across various contexts. This needs to be underpinned by the acceleration of economic transformation away from agriculture and robust social safety nets to safeguard income. Climate change adaptation and poverty reduction need not be a zero-sum game.

Editor’s note: Read our other blogs exploring topics related to sustainable growth.