Using technology to improve local revenue collection: Evidence from Malawi

Own-source revenue (OSR) in most African cities is far below potential. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) offers some exciting opportunities to improve this - from new Revenue Management Systems promoting transparency and accountability, to geo-spatial data enabling easy and affordable identification and valuation of properties for the tax roll. We explore the use of technology to improve OSR collections in Malawi and find that while the use of ICT has the potential for far-reaching benefits, it cannot overcome the challenges of a broken underlying system.

Malawi is predicted to have some of the fastest growing cities globally. To meet the needs of this growth, these cities need revenue. However, own-source revenue (OSR) collection in the cities of Malawi, like many countries across the continent (and globally) is far below potential. For property taxes, we estimated that Blantyre is collecting 38% of potential, Lilongwe 26%, and Mzuzu 39%. Business licences and market fees are even lower.

In cases like this, policymakers often turn to ICT solutions, with the potential to offer improvements in nearly all aspects of revenue administration, including:

- Identification of taxpayers: The use of geo-spatial data facilitates the identification of informal (unregistered) real estate properties and businesses, and the updating of property cadastres.

- Valuation: Recent methods to streamline the valuation of properties for tax assessments have been facilitated by the ability to process and analyse large datasets that determine value either from real estate transactions or building and neighbourhood characteristics.

- Compliance: Rapid mass-communication with taxpayers can be facilitated via SMS technology and others, which increases voluntary compliance. Hotlines, on-line portals, on-line tax filing and payment facilities create opportunities to collect taxpayer feedback, optimise processes and educate the public to improve sensitisation efforts.

- Payments: Online bank transfers or payment through mobile money can help reduce tax compliance costs and reduce pilferage of cash. Electronic payments can also improve the accuracy of tax billing and payments.

- Transparency and reporting: Data systems and standardised reporting can be automated and support improved financial decision-making. It can also create new possibilities to verify the information necessary for the calculation of the tax liability (on income, consumption, and wealth) of individual taxpayers, as well as to spot patterns, trends, and outliers.

However, in many cases, and for several reasons outlined below, these attempts at digitalisation fail. We explore this the context of Malawi, and their roll-out of revenue management systems in the four main cities, as well as other ad hoc digitalisation efforts such as the introduction of Point-of-Sale (PoS) devices for collecting market fees, online payment options, and use of satellite imagery for property identification.

Poor underlying revenue administration

IT systems are ultimately limited in their potential usefulness by the tax systems on which they are built. Where IT systems are used to automate broken or cumbersome processes, significant improvements will not materialise. For example, if the key problem of revenue administration is the lack of legislation to enforce payments of non-compliant taxpayers, ICT is unlikely to offer significant improvements.

In Malawi, rather than new technologies to monitor payments and make processes more efficient, it was improved identification and registration of taxpayers were the largest contributors to increased tax revenues. Furthermore, the one of the main constraints faced is in enforcing payments. Municipal governments can only take legal action after three years of non-payment, and even then, the process is cumbersome, and the property owner can get out of it by making only a small partial payment. Without getting these elements solved, implementing a digital revenue management system can have little impact.

Insufficient reform incentives

Optimising OSR systems is frequently not in the interests of tax collectors, politicians or economic elites, all of whom benefit from tax loopholes, lack of enforcement or reduced business or property tax rates. Evidence of these ‘political’ bottlenecks in Malawi is also prevalent, where the introduction of the Integrated Financial Management and Information System (IFMIS) met difficulties as the technology provided too many controls and made it easy to detect corruption.

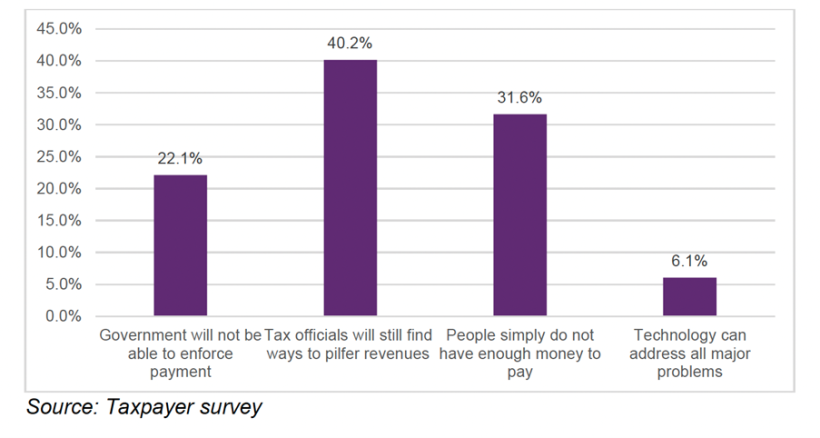

In our study, only 3% of respondents believed that no money was lost due to corruption from City Rates and Business Licenses; while only 8% believed that no money was lost from Markets. Many think more than half of revenue is lost to pilferage. Figure 1 below shows that taxpayers in Malawi also think this is the main issue that cannot be solved by digitisation.

Figure 1: Taxpayers view on key issues that digitisation cannot solve

To stop this, the right incentives need to be in place – from the tax collectors right at the bottom to the powerful decision-makers at the top, their goals need to be aligned with that of the state. Taking the example of tax collectors collecting daily market fees, 93% said that they have never received a ‘commission’ or bonus payment for good performance, while 62% answered that tax collectors are hardly ever fired for poor performance. The largest ‘penalty’ was rotation of tax collectors to a different zone, but even this is rare in practice. With neither reward for good performance nor penalties for poor performance, they have little incentive to comply with the system.

Inadequate ICT solutions

There are several reasons why ICT solutions might not meet the needs of the government. The literature cites that they could be:

- Too costly to implement or maintain.

- Too complex to operate in contexts of low capacity.

- Unable to communicate with other national/local government processes.

- Overly dependent on internet or power in environments of poor connectivity.

- Requiring extensive additional local storage and server options.

In Malawi, all of these resonated. The Revenue Management System (RMS) was not integrated with the central government IFMIS system, and many tax collectors and taxpayers cited internet connectivity issues as central to failures of the technology. Both required upfront negotiation and coordinated planning – which would have been better facilitated at the national level. The data security features were also not properly integrated in each city, limiting the benefits the RMS could bring to transparency and accountability.

Inadequate implementation

Even where systems meet all requirements of the government, they can still fall short on implementation. The process of introducing new IT systems may not be properly planned, resulting in inadequate analysis of functional and performance requirements or human resource needs. There is also often inadequate allocation of time for testing and piloting of the system.

Furthermore, while reform programmes often provide extensive technical documentation and formal training sessions, officials with limited IT expertise generally need continuous on-the-job training, which is both longer-term and more labour-intensive.

In Malawi, implementation has been hindered by the lack of comprehensive IT strategies in place in each city – that plans for the skills, infrastructure and agreements needed to facilitate the use of these new technologies. Central government could play a key role here in facilitating the enabling agreements and coordinating knowledge sharing between cities.

Conclusion

Technology can be extremely helpful in speeding up and lowering the cost of identification and valuation, as well as tracing and monitoring revenue flows and payments to improve transparency and accountability. However, Cities in developing countries need to first focus on the optimising underlying process and creating the enabling environment – particularly in properly incentivising tax collectors, having the necessary agreements and laws in place that regulate non-compliance, and investing in the accompanying skills and infrastructure.

Then, where technology can help, maximise the benefits by:

- Avoiding short-term, piece-meal solutions and enable the interoperability of systems.

- Allowing adequate time for testing and piloting the system and providing for continuous on-the-job training.

- Facilitate collective learning between cities and national government, as well as collective bargaining on software solutions.

The full report and policy brief can be found here. It also builds on previous case study here.

If you are interested in technology and local tax collection, please also see our work in Ghana here.