Building a strong evidence base for policymaking and action in cities

The IGC hosted the event "Building a Strong Evidence-base for Policy Making and Action in Cities", the first of three events in support of the call to action on sustainable urbanisation in the Commonwealth, developed jointly by the Association of Commonwealth Universities, the Commonwealth Association of Architects, the Commonwealth Association of Planners, and the Commonwealth Local Government Forum, with support from the Government of Rwanda and The Prince’s Foundation. The event was chaired by Victoria Delbridge, Head of Cities That Work, IGC. The presenters were Astrid Haas, Urban Economist, African Development Bank, Uganda; Omad Masud, CEO, The Urban Unit, Pakistan; and Matthew Adendorff, Data Lead, Open Cities Lab, South Africa. This blog distills key messages and themes from the event.

Why is an evidence base for policymaking necessary?

Astrid Haas discussed how an evidence base is important in tackling urban policymakers’ priority challenges faster and with greater accuracy. A strong evidence base can help policy stakeholders make better decisions, such as overcoming biases, improving allocation and targeting of resources, forecasting future needs for planning, and evaluating policies and programmes. It can also promote cross-city learning, so that stakeholders can leverage and build on existing ideas and the experiences of others in similar contexts rather than starting from scratch.

This is particularly crucial for cities in low- and middle-income countries who face great resource constraints and must decide between different spending priorities – including challenges in urban planning, housing, mobility, and jobs. Attracting external funding also requires bankable projects – those projects where the need and likely impact can be evidenced, and the data needed for monitoring is in place.

In the 21st century, cities also have the added pressure of climate-related constraints that they need to adapt to quickly. Finally, there are capacity constraints that having high quality data and evidence can help mitigate. For example, Freetown in Sierra Leone has automated most property tax collection, which provides both a better electronic database and frees government capacity.

What is a strong evidence base for policymaking?

For many of our challenges, we don’t need new technologies or new ideas; we need the will, foresight, and courage to use the best of these old ideas. Shoshanna Saxe, University of Toronto

An evidence base includes both usable data and actionable analysis of this data. Data could be quantitative, qualitative, or spatial; as Astrid Haas discussed, data ought to be used to solve existing problems, rather than prioritising data first and retrospectively identifying problems that it can solve. Policy actors need to ensure that they understand which data they want to access, where they can access it from, and who is going to use it, with the end goal of determining the best data to use for the problems identified.

When creating or compiling an evidence base, it is important to note that data often exists in an unusable format. For example, data might be only on paper, siloed in single schools or clinics, in completely different formats across government ministries, or inaccessible to policymakers. Part of the process in creating an evidence base is improving the storage, accessibility, quality, and frequency of data for policy decisions, either by digitising, standardising and sharing existing data, or tapping into new big data sources, such as phone or satellite data. Enabling governments to work and share data with the private sector and other important stakeholders will also contribute to a strong evidence base.

How can evidence bases for policymaking be used in practice? Case study from Punjab, Pakistan

Omar Masud, representing The Urban Unit in Pakistan, discussed how they worked with the government of the province of Punjab to improve evidence-based policymaking, using spatial data to set up a long-term direction for development. The goals of this project were:

- Creating a repository of geographically disaggregated spatial data for analysis;

- Ensuring horizontal (among sectors) and vertical (from province to local level) integration; and

- Using this data to look at the comparative advantage of regions by enhancing competitiveness of growth corridors.

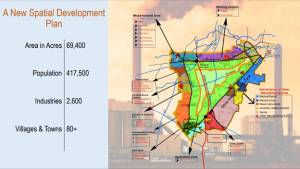

Achieving these goals requires a number of steps, including collecting data, conducting multi-sectoral analysis, developing a strategy, and finally using the data to formulate transformative and more evidence-based programmes and projects. Implementation is the most challenging stage, given the scope of the problem: Punjab has six or seven cities with population sizes of 10+ million and urban policy is made at the local, regional, and provincial levels. Therefore, data design and representation needs to address all three levels.

In one instance, the Urban Unit found that the vast majority of manufacturing industries are small and located close to arterial roads and highways in the province. Using the spatial representation of manufacturing units in the province, the Urban Unit has advocated zoning of economic corridors to increase competitiveness and growth of the manufacturing industries across the province. Mapping industrial zones around the major highways where the units are located and providing infrastructure support to these industrial zones or economic corridors (see figure below) would be a more flexible and practical strategy than creating conventional industrial parks. The Urban Unit is currently working with cities and towns on a legal framework to implement the economic corridor approach on a regional basis.

The above map shows the case of Sialkot Region Economic Triangle

From this experience, what they learnt was that it is important to create an interface between domain expertise and data experts – local officials provide domain expertise, such as industrial, legal, and city requirements, and data experts can ensure they use spatial data in a way that is relevant to the officials’ needs. It is important to interface with the legal system to develop a mechanism for data sharing openly and transparently. In this context and others, data-focused organisations will have to consider the challenges around scaling up and scaling across, as cities and regions may have different and complex legal priorities and mandates. Questions remain regarding whether to centralise or decentralise data holdings, and relatedly, where to place analytical expertise in capacity-constrained environments.

Data sharing across cities

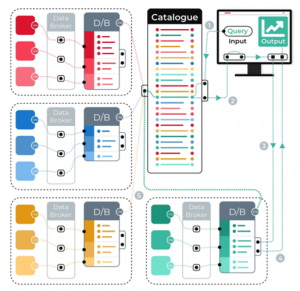

Matthew Adendorff compared centralised and decentralised data in more depth. A centralised format has all the data – for example, data on water, electricity, and waste – together in a standardised schema. This is ideal, but at the scale of a city, the number of departments with different systems are conspicuous by their absence. Where these numbers exist, it is often still difficult for policymakers and researchers to access because of security concerns. A distributed, decentralised data architecture lets data live where it is created, with a catalogue that allows users to see what the data contains, where the data is stored, and how it can be accessed.

When each city has a strong evidence base, the cataloguing can further be used across cities, allowing cities to learn from one another, or scaling up to the national scale (see figure below).

A successful common evidence base between city stakeholders requires a consolidated, needs-driven structuring of information to achieve policymaking objectives. This requires common data principles – objectives, sovereignty of data, and sharing mechanisms – as well as an explicit focus on ensuring the data is inclusive of all residents. The latter can be achieved, for example, by not requiring data to be tied to a formal address, which are often absent in informal settlements. It also requires an understanding of governance frameworks and data taxonomy – the structures and reporting that needs to be put in place to ensure requirements are met.

Strong evidence bases open up possibilities, but the right frameworks must be in place

A strong evidence base allows policymakers with resource constraints to determine which problems to focus on and how to address these problems with data. Accessible and transparent data can be used to address challenges from taxation to industrial development more efficiently. This data can be used and shared at the city level, the provincial level, or even the national level, provided the data is representative, and the legal frameworks and governance structures are in place. A smart city is a city that uses and collects evidence to improve the lives of people.

With the right systems in place, data-focused organisations can work closely with the government and other important stakeholders to ensure that data is being used to address the city, region, or country’s most salient challenges. As policymakers and organisations continue to develop best practices, it will be important to document and share these ideas to create smart and interconnected cities around the globe.