Urban density, trust, and knowledge sharing in Lusaka

A recent IGC study looks at the relationship between urban density, in the context of Lusaka, trust and knowledge sharing among small-scale manufacturing firms.

Zambia’s urban population is set to reach 12 million by 2030 – double its urban population as of 2015. Economic theory suggests that urban density can facilitate economic growth through agglomeration economies – yet applications of this theory have focused on the developed world where there tend to be i) strong legal institutions and ii) relatively high levels of interpersonal trust. This study seeks to uncover the extent to which knowledge sharing, and other benefits of agglomeration, rely on interpersonal trust and local institutions. Preliminary results from a census of Lusaka’s firms suggest that both trust and knowledge sharing between small-scale manufacturers are correlated with urban business density.

Urban density and economic opportunities

The developing world is rapidly urbanising: according to the United Nations, the urban population in developing countries will increase by approximately 2.5 billion people by 2050 (United Nations, 2014). It estimates that the number of urban dwellers in Zambia will increase by four times by 2050double by 2030, to almost 26 million individuals. In Africa, the number of urban dwellers is expected to increase by almost three times to around 1.3 billion people.

Image credit: bathyporeia

The Zambian government recognises the critical role that urbanisation plays in the country's future and is currently in the process of developing a National Urbanisation Plan - motivated in part by the acknowledgement that “by ensuring density, diversity and innovation, cities can boost economic activities” (Ministry of Local Government and Housing Zambia, 2014).

Urban density generates opportunities for agglomeration economies, defined as the benefits that accrue to people and firms from locating near to one another, such as cost reductions in exchanging goods and ideas. This has been well known in economics since Alfred Marshall (1920), who was among the first economists to emphasise the potential benefits of industrial agglomeration in terms of labour demand, market pooling and knowledge sharing. The way in which these benefits could inform growth policies is a topic of particular relevance, especially in a country like Zambia, in which more than 60% of firms have less than 19 employees (Bloom et al. 2014).

Urban density generates opportunities for agglomeration economies, defined as the benefits that accrue to people and firms from locating near to one another.

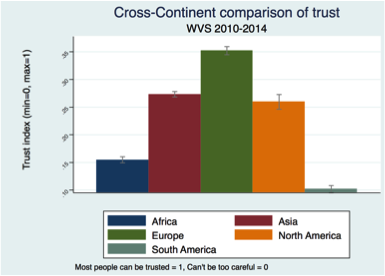

Taking advantage of the opportunities offered by urban density requires capabilities such as trust, interpersonal skills and access to social networks (Bowles and Gintis, 1976). Indeed, several studies have shown that trust is positively correlated with economic development (Knack and Keefer, 1997). However, the effect of cities on trust is ambiguous. While cities increase the scope for social interactions and flows of information, they also increase the costs associated with monitoring behaviour, thereby potentially inducing greater moral hazard. This tension threatens the capacity of individuals and firms to reap the benefits afforded by urban density. In societies lacking trust and social capital, the positive externalities generated by close proximity might be left unexploited. This maybe particularly relevant in many fast-growing African cities; data from the World Values Survey show indeed that African countries generally have low levels of trust (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Continental levels of trust (data from World Values Survey, 2010-2014)

In societies lacking trust and social capital, the positive externalities generated by close proximity can be left unexploited.

The study: do trust and cooperation correlate with urban business density?

Can African cities foster the spread of ideas and knowledge among small-scale firms, or do low levels of trust limit these possibilities? This study provides micro-level descriptive evidence on the spatial patterns of economic activity among small business owners in one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa: Lusaka, Zambia. Using new proprietary survey data, it investigates whether the levels of cooperation and trust systematically vary with business agglomeration within the city.

Can African cities foster the spread of ideas and knowledge among small-scale firms, or do low levels of trust limit these possibilities?

The data: a spatial mapping of Lusaka’s businesses

The first stage of the study, conducted between May and September 2016, involved the spatial mapping of all the businesses in the city of Lusaka. The resulting “Lusaka Census of Urban Entrepreneurs” contains basic information on approximately 48k businesses across all industries and firm size.

The Census also included a short survey administered to all business owners[1] in the city with fewer than 20 employees belonging to manufacturing, mining, and construction. There were 2,216 respondents, which accounts for 58.3% of the firms in these sectors[2]. Data was collected on business practices and history, levels of trust, collaborative behaviour with other businesses, and demographics.

The combination of these datasets provides evidence of agglomeration patterns within the city and whether business density is correlated with knowledge sharing and greater trust between business owners.

Trust in Zambia and among Lusaka small-scale manufacturers

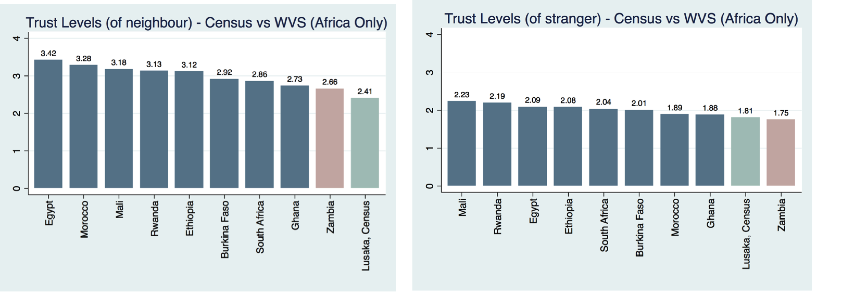

Respondents’ levels of trust were elicited by asking the extent to which they trusted their neighbours and strangers respectively (trust completely = 4, somewhat = 3, not very much = 2, not at all = 1). The average level of trust with respect to both neighbours and strangers in the interviewed population of manufacturers is particularly low when compared with Africa as a whole (World Value Survey, wave 2005-2010). With an average level of trust in neighbours of 2.41, interviewed entrepreneurs have a lower level of trust with respect to Zambia as whole in 2007 (2.66) and also many other countries in Africa, such as South Africa in 2006 (2.87) and Ethiopia in 2007 (3.12).

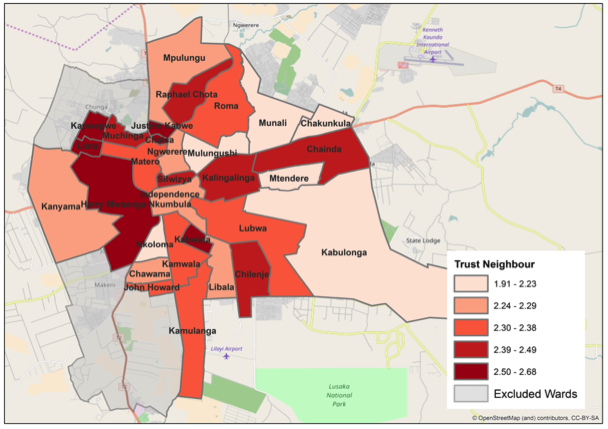

However, there is some degree of spatial heterogeneity even within Lusaka. This can be seen in Figure 3, which depicts the average level of trust in neighbours at the ward level.

Zambia’s population is seen to demonstrate a low average level of trust, even within Africa.

Figure 2. Trust levels in African countries (WVS, wave 2005-2010 and Census data, 2016)

Figure 3. Zambia’s average level of trust at the ward level (Census data, 2016)

Trust is positively correlated with business density

The evidence from the Lusaka Census of Urban Entrepreneurs demonstrates a positive correlation between the density of businesses in the same sector and trust in neighbours.[3] In other words, when businesses in the same sector locate near one another, their owners display greater trust levels, but not with respect to strangers. This result can be explained by a selection effect, where more trusting business owners decide to co-locate next to each other, or by a neighbourhood effect, where proximity to similar businesses fosters reciprocal trust, or a combination of the two. The correlation is not affected by other characteristics of the owner, such as gender and experience, or features of the geographical administrative area where the business is located (i.e. the Census Supervisory Area), such as their level of economic activity.

Knowledge sharing is positively correlated with business density

The study proposes three measures of knowledge sharing: business cooperation, teaching business skills to others and talking about business with other business owners.

Respondents’ propensity to cooperate with other businesses was measured by their self-reported history of engaging in one or more types of cooperative behaviour. Respondents were asked whether or not they had ever 1) shared a large order, 2) jointly ordered supplies, 3) asked or gave business advice, 4) borrowed/lent machines or subcontracted employees with another business in the same sector.

The study finds that the proportion of cooperative activities undertaken by the owner – among the four listed in the survey – increases when the density of similar businesses (measured as above) is greater. Same-sector business agglomeration is also positively correlated with the likelihood that the owner learned the business from another entrepreneur and greater communication between owners (on business and personal matters).

The regression analysis further suggests that some of these effects are driven by businesses locating in formal markets (either established by a cooperative or a council). Indeed, business owners within markets tend to cooperate with other similar businesses and to teach other people how to operate their business more often, as compared to owners in the same sector who are located outside such a market. Anecdotal evidence suggests that these markets may provide institutional mechanisms that facilitate cooperation between businesses within the market (for instance, by providing arenas in which disputes between businesses can be aired and resolved).

Business owners within formally established markets tend to cooperate with other similar businesses and to teach other people how to operate their business more often, as compared to owners in the same sector who are located outside a market

Conclusion: capitalising on urban density

Our results are consistent with the pattern one would expect if agglomeration economies held. However, two caveats should be kept in mind. First, our results cannot answer the direction of causality – they are consistent with both a causal mechanism of density on trust or a selection mechanism, in which business owners with higher levels of trust co-locate. Second, without robust evidence on the financial performance of these firms, it is not clear whether greater knowledge sharing leads to enhanced profitability.

The patterns described in the research hold important insights. In particular, they call for a deeper understanding of the relationship between agglomeration and trust in fast-growing urban environments. Clusters are at the heart of the innovation policies of many OECD countries - including Argentina, Belgium, France and Portugal – as well as Sub-Saharan countries, but little is known about the mechanisms, which lead clusters to succeed or to fail. Our correlations hint at the fact that local institutions, such as formal market structures, either spontaneous or centrally planned, could play a crucial role in fostering business interactions and knowledge sharing; as such, their design and development are important variables to be considered by policy makers.

To conclude, the potential for cities on the African continent to thrive depends on the capability of their inhabitants and entrepreneurs to exploit the positive externalities generated by urban density. These capabilities can also be supported and even substituted by more or less informal institutional arrangements. However, are these institutions apt to favour growth beyond small scale, or should they be supported by more formal agreements?

The next steps of the project aims at provide an answer to this question.

[1] If the owner was not available, the interview was conducted with the main manager.

[2] 23.5% didn’t give consent for the interview and 18% were not found after three attempts.

[3] In the main specification, density was measured as the (log) number of businesses in the same sector within the same Census Supervisory Area (CSA) divided by the CSA area.