Improving asset and debt management in developing cities

Many developing cities have a large pool of wealth in their public assets, however they lack the inventory and strategic capacities required to untap the potential revenue. Well managed cities are able to harness their assets, ensuring they have predictable streams of finance that can be used to pursue inclusive and sustainable development plans.

Strategic management of city assets

Increasingly, cities are beginning to recognise the importance of streamlining the management of their assets. For example, several African cities are currently undertaking widespread property registration reforms, with the inclusion of market valuations, to inform decisions on the use of land and address financial needs for infrastructure investments (Peterson, 2009).

There are three critical pillars that cities should bear in mind when looking to rationalise asset management programs:

- conducting a diagnosis of initial inventory,

- classification of assets, and

- capital investment plans for the use of asset wealth (Kaganova and Kopanyi, 2014).

Implementing these strategies would help authorities to identify their asset holdings, assess private and public obligations, and improve participation and accountability in the use of city assets.

Recognising land as one of the most valuable assets for a city

Of all assets available to developing cities, urban land, and the physical properties on the land, represent the largest source of untapped revenues on offer, making land-based financing options a critical resource for fast-growing cities. These options can take the form of:

- Sale or lease of land in the case of public holdings.

- Land-based revenue tools: Betterment fees, sale of property rights, impact fees and taxes on private land holdings (Anderson, 2011).

- Public-private collaboration for joint redevelopments.

- Collateralisation of land to secure institutional investments and bolster creditworthiness.

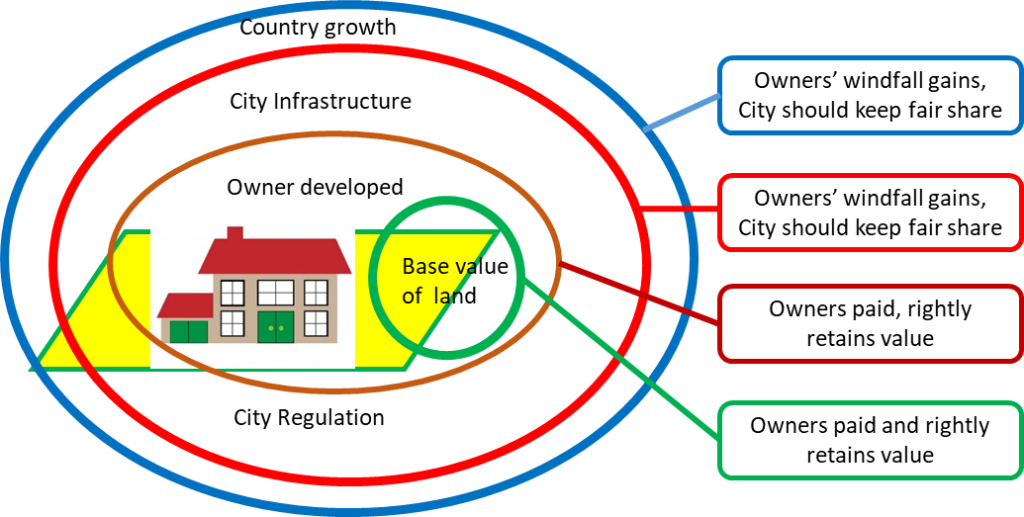

In the case of private land holdings, the market value also includes a very large share of wealth generated by the city or national government from factors such as:

- Off-site infrastructure: e.g. roads, water and sanitation systems, electricity and street lighting, schools, and/or health facilities.

- The economic power of the local area, city, or national economy.

- Population growth pressures, which drive up land prices.

Figure 1: Land-value components, factors, and fair shares

Source: Authors based on Hong & Burbaker, 2010

Source: Authors based on Hong & Burbaker, 2010

Accordingly, cities should look to extract a fair share of any gains in such land values through fees and taxes. Examples of these financing mechanisms can be found across the developed and developing world. For example, Bogota, Colombia, has financed more than half of its arterial road network through betterment levies (Uribe, 2010). In the United States, cities regularly make use of tax-increment financing, a procedure where future property taxes are earmarked to pay for infrastructure or to issue municipal bonds (Merk et al., 2012). Finally, several cities, such as Sao Paulo and Mumbai, sell development rights to extract portions of the value of new construction in high density zones. São Paulo in particular, has been issuing tradable building rights through public auctions for several years now (Smolka, 2013).

When cities decide to lease or sell land, it’s important to recognise that land has no one single value, instead values will depend on things such as off-site infrastructure preparations as well as legal rights and permits. Land is undoubtedly much more valuable when zoning codes, use permits, and regulations are favourable to the investors, because it means they can ensure their future business plans and profit motives are compatible with the goals for urban development in the area.

Methods for valuing assets and making infrastructure revenues more sustainable

Only through accurate and timely valuation can urban authorities properly identify and assess the obligations of landholders for taxes and fees as well as the suitability of certain areas in wider infrastructure investment plans. Typical methods for valuation include recording and documentation of market value (the estimated sale price of an asset at competitive auction); sales comparison approaches for small properties and vacant land (comparing similar recently sold assets to the subject (Haas & Kopanyi, 2018); estimated income approaches for commercial properties; and cost approaches for new constructions or special properties (Lafuente, 2009).

Once infrastructure is in place, it is also important to tap into a range of non-tax sources. For instance, user fees levied on infrastructure like public transport can provide the revenues that are critical to deliver services and ensure accountability. Key issues for authorities to consider when dealing with user fees include the overall setting of tariffs; affordability assessments and possible requirements for subsidisation; assessments of costs for the public administration of tariffs; and capacities for collection and enforcement.

Improving the portfolio of borrowing options for developing cities

A major issue for the capital and operating expenses of key infrastructure and services in developing cities is that there is typically over-reliance on central government and international aid transfers for financing. However, these transfers are often neither sufficient, nor stable enough, to sustainably finance such long-term and large-scale projects.

Access to debt markets is a critical element of municipal financing, which should be fully justified provided that cities have the capacity to repay loans, which largely depends on:

- The city’s financial prospects and fiscal performance;

- the borrowing terms, interest rates, and maturities;

- the structure and size of debt stock; and

- the national framework and constraints.

To date, however, developing cities have scarcely issued bonds due to their undeveloped financial markets and perceived lack of creditworthiness. South Africa, Mexico, and India are the positive exceptions, and although Dakar in Senegal made major progress towards preparing for its first bond in 2015, the city was thwarted due to regulatory conflicts with the national government.

Figure 2. Creditworthiness and capital market define the path for development financing

Source: Authors

Source: Authors

To tap into capital markets, cities will need to diversify and strengthen their sources of revenue; improve their capacity to adjust fiscal policies; and borrow in line with their payment capacity. Financial ratios and benchmarks can play important roles as tools for self-diagnosis as well as for investors and rating agencies (Figure 2).

As for cites with low debt capacity, they may be open to exploring alternative financing options such as soft loans provided by the World Bank, the Public – Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF), and USAID, who have financed programmes to help cities improve fiscal management, strengthen their revenue base, and move towards capital markets.

Coordinating with national governments is also key as they will have to set clear frameworks for limits and regulations; gain clarity about tax powers and the use of transfer; and receive guidance on what to do in case of default. Credit enhancements performed in isolation from any realistic national fiscal strategy may help a credit issue but cannot guarantee that the city gains the trust of the market for future issuance.

Asset and Liability Management (ALM) in developing cities

Asset and liability management (ALM) is a new approach being used to make city administration and political leaders accountable for the continued management and improvement of municipal wealth. The principle behind ALM is to ensure that the liabilities are managed in parallel to the assets – as in standard corporate accounting.

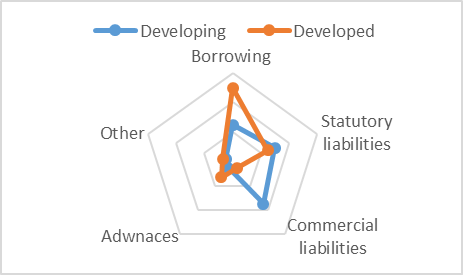

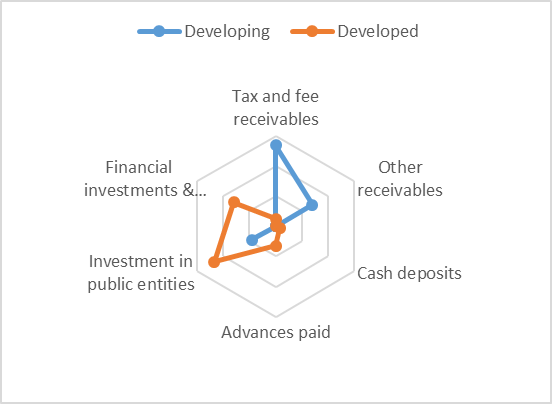

Using the ALM approach, we see that cities in developing countries typically have liabilities that are extremely difficult to monitor and manage. They tend to have low or no formal debt but large accumulations of hidden debt in the form of delayed statutory contributions and overdue commercial liabilities. Contrastingly, although developed cities have considerable borrowing and statutory liabilities, these are all duly registered and in-line with standardised recording procedures.

Cities in developed countries also tend to have a reliable asset inventory, and value strategic assets before the sale of investment transactions as part of the strategic management of debt. On the other hand, cities in the developing world have poor or absent asset inventory, which prevents them from using property assets strategically to invest in or support borrowing. These shortcomings make city administrators and political leaders unaccountable for maintaining and increasing the wealth of the city.

To give an example, Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the difference between Nairobi and Australia Capital Territory (ACT): Note that Nairobi is burdened with a large volume of uncollected taxes, fees, and other receivables and most assets are nonperforming with a low present value. ACT, however, displays financial assets dominated by investments in public entities and financial investments that can be mobilised in the short-medium term.

Figure 3. Composition of financial assets in developed and developing cities (Nairobi and Australia Capital Territory)

Source: Authors based on Kopanyi-Omolo, 2018.

Source: Authors based on Kopanyi-Omolo, 2018.

Figure 4. Composition of financial liabilities in developed and developing cities (Nairobi and Australia Capital Territory)

[caption id="attachment_27399" align="alignleft" width="552"] Source: Authors based on Kopanyi-Omolo, 2018.[/caption]

Source: Authors based on Kopanyi-Omolo, 2018.[/caption]

The bottom line is that to accommodate the needs of fast-growing developing cities, urban authorities need to tap into a much broader range of financing streams, including revenues from taxes they levy, revenues from non-tax sources they have control over, and revenues from external investment. Acquiring this funding, particularly from external institutional investors, will require major reforms in asset and debt management so that developing cities can identify their inventory of wealth available and reliably raise money from a range of local sources.

References

Anderson, J. E. (2012). “Land lease revenue and urban public finance: Evidence from Chinese cities”, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Accessible: https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/collecting-land-value-public-land-leasing_0.pdf

Haas, A. and Kopanyi, M. (2017). Taxation of Vacant Urban Land: From Theory to Practice, Policy Note, International Growth Centre, London School of Economics. Accessible: https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/201707TaxationVacantLandPolicyNote_Final.pdf

Kaganova, O. and Kopanyi, M. (2014). Managing Local Assets, Chapter 6 in Municipal Finances – A Handbook for Local Governments, Farvacque-Vitkovic and Kopanyi eds., World Bank, Uribe.

Kopanyi, M. and Omolo, M. (2018). Nairobi City County Asset management, Case Study, World Bank (forthcoming).

Lafuente, M. (2009). Public Management Reforms and Property Tax Revenue Improvements: Lessons from Buenos Aires, Working Paper Series on Public Sector Management, World Bank, LAC. Working paper 0209.

Merk, O. et al. (2012). Financing Green Urban Infrastructure, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, 2012/10, Paris.

Peterson, G. (2009). Unlocking Land Values to Finance Urban Infrastructure, World Bank-PPIAF. Washington DC.

Smolka, M. (2013). Implementing Value Capture in Latin America: Policies and Tools for Urban development, Policy Focus Report, Cambridge, Mass.: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Uribe, M. (2010). “Land Information Updating, a De Facto Tax Reform, Bringing up to Date the Cadastral Database of Bogota”, Innovations in Land Rights Recognition Administration and Governance. 180-207. Washington DC: World Bank. Edited by Deiniger, K., Augustinas, C., Enemark, S. and Munro-Faure, P.