Using e-governance data to improve public service delivery: Evidence from land record changes in Bangladesh

Improving monitoring and evaluation information flows in government bureaucracies can improve service delivery even without explicit incentive structures.

Studies have shown that better incentive structures for civil servants improve the way they provide public services (Finan et al. 2017). However, due to political constraints it is often difficult to introduce pay-for-performance or other explicit incentive structures in government bureaucracies. Despite the existing evidence that incentive structures can be successfully implemented, they are rarely used by governments in low- and middle-income countries.

The lack of explicit incentive systems does not mean that the senior civil servants who manage lower level bureaucrats lack the power to reward or punish them through other means. For example, supervisors in government bureaucracies can often influence the future postings and career paths of lower level bureaucrats, which can also be a strong motivating factor for civil servants (Khan et. al. 2019). The power of supervisors often becomes obvious when they directly observe junior bureaucrats. In these instances, they often put in special effort in performing the tasks assigned to them.

One problem that managers of civil servants face is the lack of access to relevant information to systematically evaluate their subordinates. This means they cannot use their authority to provide incentives to motivate their subordinates. Improved information systems could allow senior civil servants to better align the existing incentive structures with service delivery goals.

Junior civil servants in Bangladesh

In an experiment in Bangladesh we use data from an e-governance system to provide a monthly performance scorecard for junior civil servants. The scorecards summarise the data into easily understandable performance metrics and are sent to the junior civil servants as well as their superiors. The results from our experiment suggest that we can improve bureaucratic efficiency by simply improving the information about civil servant performance, even without tying the performance to an explicit incentive structure.

Land record changes in Bangladesh

When land has changed owners in Bangladesh, either through sale or inheritance, the official land record has to be changed and a new Record of Right issued. These land record changes (called mutations) are conducted by civil servants holding the positions of Assistant Commissioner Land (AC Land). AC Land is a junior position in the Bangladesh Civil Service and each AC Land heads a sub-district (Upazila) land office. The government has mandated that land record changes should take no more than 45 working days, but in practice delays beyond this time limit are common.

An e-governance system known as the “eMutation system” is currently being implemented throughout Bangladesh by a2i, a government agency tasked with the mission of fulfilling the vision of “Digital Bangladesh”, and the Land Reforms Board of Bangladesh. The goal of this is to simplify the process of land record changes for both the applicants and the civil servants processing the applications. The e-governance system also has the additional benefit of generating administrative data on the land record changes. However, until the start of our experiment, this data was not presented in a format enabling evaluation of the performance of specific AC Lands.

The performance scorecard experiment

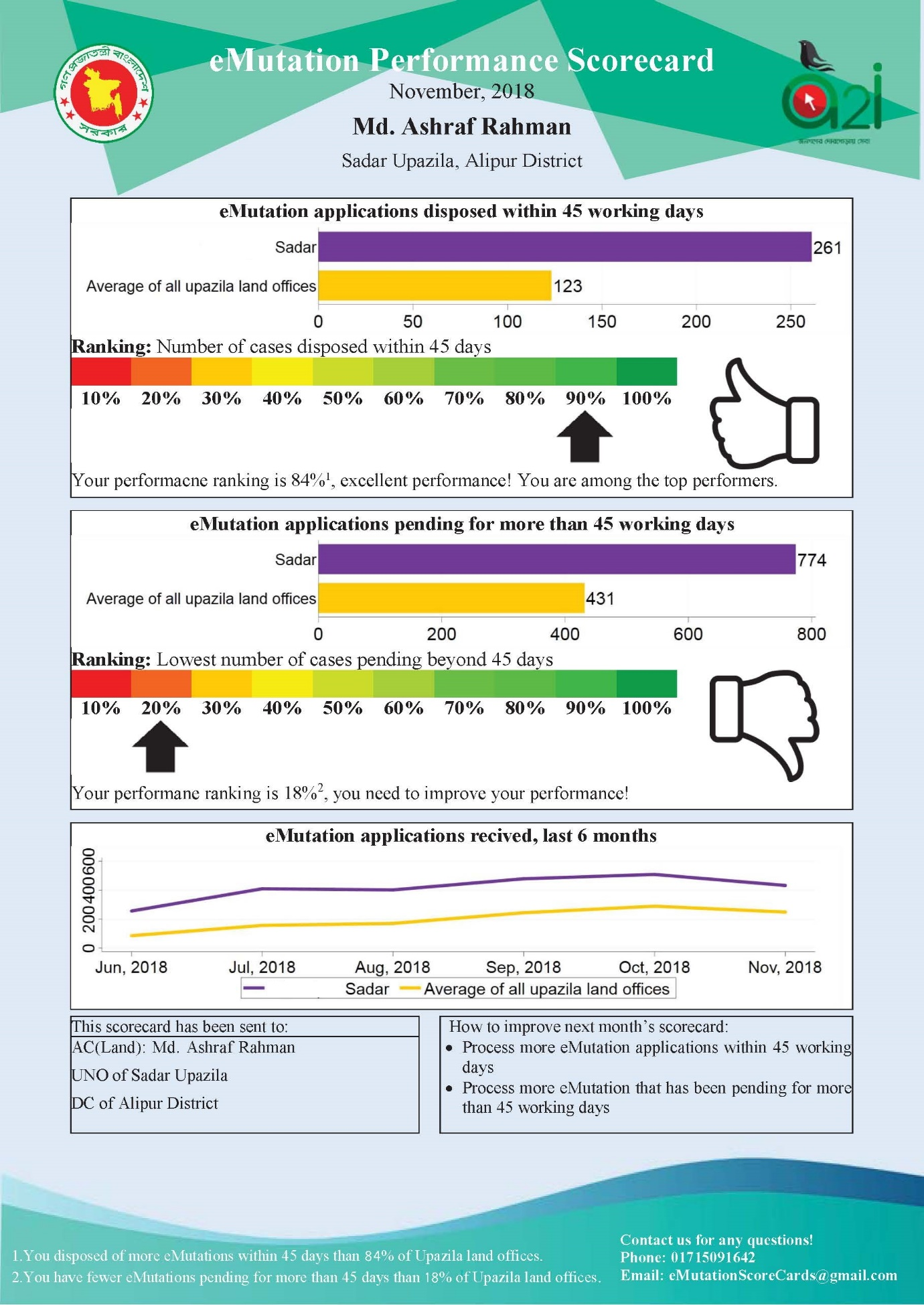

Since September, 2018, we have been sending out a monthly performance scorecard to randomly selected land offices. The scorecard is focused on reducing the number of delays beyond the 45 working day limit. In particular, it highlights the number of applications that were processed within 45 working days and the number beyond 45 working days. These figures are then compared to the average among all land offices and each office receives a percentile ranking between 0 and 100%. An example of a performance scorecard can be seen in Figure 1 below. The scorecard is sent to the AC Land, their direct superior, the Upazila Nirbahi Officer, and their superior’s superior, the Deputy Commissioner of the district. 56 out of 112 land offices that were using the e-governance system were randomly chosen to receive the monthly scorecards enabling us to measure causal effects.

Figure 1: Example Performance Scorecard

Since the performance indicators in the scorecards are not directly tied to any material incentive, we are relying on two potential mechanisms for the scorecards to have an effect. One is that the bureaucrats care about the opinion of their superiors. As hypothesised above, this seems like a plausible mechanism since their superiors have substantial power over their future promotions and postings. The second potential mechanism is that being measured and compared to your peers creates an additional intrinsic motivation to perform well, similar to how being compared to your neighbours has been shown to have an effect on electricity consumption (Allcott 2011).

Effects of the scorecards

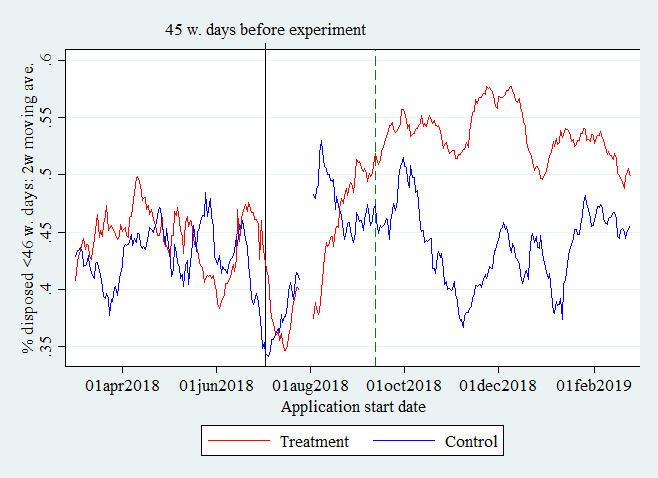

Figure 2 shows the effect of the performance scorecards on the fraction of applications processed within the time limit. We find that for a typical land office the performance scorecard increased the fraction of applications processed within the time limit by nine percentage points, an increase of 23%. The average processing time in a typical land office is estimated to have been reduced by 22% or 22 working days by the performance scorecards.

Figure 2: Fraction of applications processed within time limit

Note: The effect can in principle have started for applications started 45 working days before the first scorecard was sent (represented by the solid black vertical line). The gap in the middle of the time line is due to a server error that caused the e-governance to shut down for about a week in late July, 2018.

Note: The effect can in principle have started for applications started 45 working days before the first scorecard was sent (represented by the solid black vertical line). The gap in the middle of the time line is due to a server error that caused the e-governance to shut down for about a week in late July, 2018.

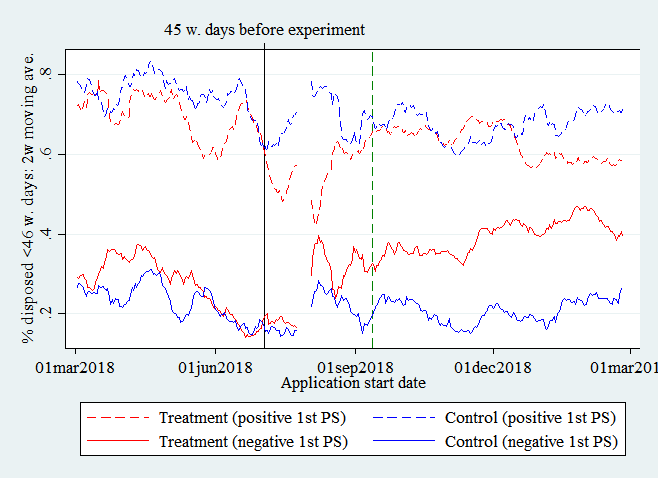

One interesting question is whether positive or negative performance feedback has the largest effect on subsequent performance. We can answer this question by measuring the effects of the scorecard separately for the top vs. the bottom half of the offices in terms of the first month’s performance i.e. the performance that could not have been affected by the scorecard. In Figure 3 we can see that the effects of the scorecards are entirely driven by the offices that received a negative first scorecard.

There are several reasons for why this might be the case. First, it is possible that negative performance feedback creates a stronger desire to improve one’s performance for subsequent scorecards. Second, poorly performing offices may have a larger scope for improvement since there is more “low-hanging” fruit in terms of increasing efficiency.

Figure 3: Effects for offices with a positive vs. negative first scorecard

Regardless of the mechanism, this result implies that the type of recognition systems that are common place in low- and middle-income countries, recognising outstanding performances among bureaucrats without addressing the inadequate performances of other bureaucrats, may be ineffective.

Potential unintended consequences

A common critique against quantitative performance evaluations is that they may cause civil servants to focus only on what is measured to the detriment of other objectives that are not measured or not even measurable. This is clearly a possibility for the performance scorecards in this context since they emphasise the speed of service delivery of one particular service while other dimensions of the civil servants’ responsibilities are not included. To understand if such unintended consequences are taking place, we will conduct a survey of applicants to look for negative spillovers on tasks that are not part of the scorecards. Furthermore, we will analyse any potential effects on the quality of land record decisions by measuring the propensity to reapply after a rejection, as well as the overall satisfaction with the land record change process.

Policy implications: The potential of e-governance data

As more and more public services are delivered using e-governance systems, the cost of monitoring and evaluating civil servants’ performance has drastically decreased. Our experiment is adding to an emerging literature on how improving monitoring and evaluation information flows in government bureaucracies, can improve service delivery even without explicit incentive structures (e.g. Dodge et al. 2017). The results of the experiment show that using the data generated by e-governance systems for monitoring and evaluation has significant potential to improve bureaucratic efficiency.

References:

Allcott, H (2011), "Social norms and energy conservation", Journal of Public Economics, 95(9-10): 1082-1095.

Dodge, E, Y Neggers, R Pande and C Troyer Moore (2017), "Having it at hand: How small search frictions impact bureaucratic efficiency", Working Paper.

Finan, F, B Olken and R Pande (2017), "The personnel economics of the developing state", Handbook of Economic Field Experiments, 2: 467-514.

Khan, A, A Ijaz Khwaja and B Olken (2019), "Making moves matter: Experimental evidence on incentivising bureaucrats through performance-based postings", American Economic Review, 109(1): 237-70.