All Peas in One Basket: Lessons from the 2017 Pigeon Pea Crisis

In recent years, the rapid expansion of pigeon pea production provided a boost to the rural economy of Central and Northern Mozambique. However, the 2017 price collapse created a crisis in the main production areas that calls attention to the need to improve the monitoring of market trends and to launch a joint effort aimed at diversification.

During the past decade, the solid growth of Mozambican pigeon pea production was driven by Indian demand, which was formalised in the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on the production and marketing of pigeon peas and other pulses, signed by the Governments of Mozambique and India in 2016. More than 1.2 million farmers in Central and Northern Mozambique counted on this crop to provide revenue in 2017. However, right from the beginning of the harvest season, they faced a precipitous price decline, from approximately MZN 45/kg in 2016 to MZN 5/kg in 2017. The resulting lack of purchasing power by the farmers has led to an economic crisis in the main pigeon pea growing districts, especially where most farmers had no alternative cash crops. The price decline was caused by a bumper harvest in India, resulting from good 2016 monsoon rains, but it was worsened by the inefficiency of the Mozambican authorities in managing the situation, particularly in the context of the MoU, which paralysed exports.

India is not only the major producer, but also the main importer of pigeon peas, accounting for 90% of global imports, and thus representing the only sizeable export market. Pigeon pea is processed into dhal, the main source of protein for the majority of Indians. For various years, Indian production could not keep up with growing domestic demand, leading to a deficit of more than 500,000 tons per year.

Over the last decade, a couple of African countries; Mozambique and Tanzania, emerged as significant pigeon pea exporters to India. Various NGOs and development agencies partnered with the private sector to promote pigeon pea production among Mozambican farmers, convinced that the market was guaranteed. As a result of these efforts, production expanded rapidly, reaching almost 200,000 tons in 2016. Most of the production takes place in the provinces of Zambézia and Nampula, the most densely populated parts of the country. From the 2016 crop, Mozambique exported more than 170,000 tons, corresponding to USD 125 million.

The Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, visited Mozambique in July 2016 and signed the MoU through which he formalized his country´s commitment to import 125,000 tons in 2017-18, gradually increasing the annual volume to 200,000 tons in 2020-21. Subsequently, the Mozambican government also intensified pigeon pea promotion among farmers, to reach the MoU targets. These efforts, together with the high prices of 2016, led to a further jump in the number of farmers and cultivated area compared to 2016, translating into a production of approximately 250,000 tons, the largest ever recorded.

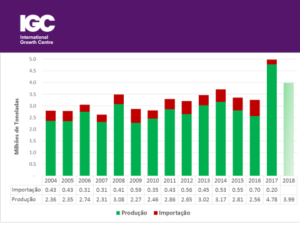

However, India also stimulated domestic production, which, combined with good monsoon rains and high farm-gate prices in 2016, led to an all-time record production in 2017, enough to satisfy domestic demand and still be left with 1 million tons (Figure 1). As a result, the pigeon pea price in India collapsed, provoking farmer protests. In response, the government took measures to protect its farmers, introducing a 200,000 ton pigeon pea import quota for the financial year 2017-18.

Figure 1. Indian Pigeon Pea Production and Import

Source: IGC, based on data of Indian Ministry of Agriculture

Following these developments in India, the farm-gate price in Mozambique fell by 90%. Simultaneously, the price of other important agricultural crops, such as maize, dropped as well. This meant that many farmers were left without any financial revenues, and subsequently without the resources to invest in the next agricultural season, which may lead to a reduction in overall cultivated area. Further, the reduced purchasing power of the farmers created multiplier effects in the local economy. The depth of the crisis varies by district, with the worst impact felt where most farmers had no other cash crops, besides pigeon pea, which is the case in most of Middle and Upper Zambézia. In this region, virtually all shop-owners refer that their business volume declined by more than 50% compared with last year. (See the article A Socioeconomic Crisis in Rural Mozambique).

The current situation reveals the danger of depending on a single cash crop, particularly if that crop depends on a single market. To avoid similar scenarios in the future, the IGC study[1] recommends that Mozambique takes the following measures

1. Improving Pigeon Pea Statistics

There is a lack of reliable statistics on Mozambican pigeon peas, both in national and international databases. National production statistics are hidden in the wider category of “beans”, as no distinction is made between the various types of beans and peas, despite the fact that these are products with very different markets. Therefore, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (MASA) should orient the major pigeon pea producing districts to systematically collect pigeon pea statistics, to be integrated in the government´s official reports on the agricultural sector. These production estimates should also be included on FAOSTAT, the FAOs online database. Finally the Agricultural Market Information System (SIMA) should start reporting the pigeon pea price in a set of important market towns.

2. Market Intelligence

The 2017 season provides a stark reminder of the danger of investing without a good understanding of market trends. In the case of pigeon peas, special attention should be paid at the end of September, when the Indian Ministry of Agriculture publishes its first estimate of pigeon pea production of the kharif season, the harvest of which takes place mainly in January, based on estimates of the cultivated area and an assessment of the monsoon rains. As such, the forecast of a record Indian harvest for 2017 was already available in September 2016, which is three months before Mozambican farmers start planting. Based on this information, the current situation in the Mozambican countryside could have been anticipated. Therefore, the Mozambican government should improve market intelligence by monitoring international pigeon pea developments, particularly in India, the main market. In fact, Figure 1 shows that current estimates point at another bountiful harvest, of 4 million tons, which means there is no perspective of a substantial price increase to the Mozambican farmer in 2018.

3. Monitoring Trade Data

Mozambique’s official export statistics suggest that annual pulses exports have been around USD 20 million in the last two years. Indian import statistics, however, show that it has been importing USD 120 million per year from Mozambique. This represents a very large discrepancy, the causes of which should be further investigated, as it points at the possibility of capital flight or of serious deficiencies in the data capturing process at the ports.

4. Diversification

One of the main reasons for the current situation in Zambézia is the strong reliance on a single cash crop with a single market. Therefore, a diversification effort is needed, in the following dimensions:

Market Diversification. The government should promote the image of the country as an exporter of pigeon peas and other pulses. Although India is practically the only importer of raw pigeon peas, the market for peas that have been processed into tur dhal is more diversified, even if smaller.

From a longer term perspective, Mozambique should identify partners in Europe and North America to promote the consumption of pulses. In these markets, there is a strong trend of consumers becoming more aware of the effects of their consumption patterns on personal health, but also on climate change, global poverty and inequality. Pigeon pea is a crop typically produced by small farmers and has highly favourable characteristics for soil health, particularly through nitrogen-fixing. Finally, it is rich in protein, and thus ideal for vegetarians, a continuously growing group of consumers.

Promoting Domestic Consumption. Despite representing a low-cost, yet highly nutritious food crop, rich in protein, vitamins and minerals, domestic consumption is limited. To guarantee a local market for pigeon peas, Mozambique could take advantage of the crop´s potential and associated benefits, by promoting domestic consumption through awareness-creation and the inclusion of pigeon pea in national food assistance programs, such as school feeding and humanitarian aid.

Diversification of Pulses Production. Considering that Mozambique already has a tradition of producing pulses, which are well-suited to smallholder conditions, it makes sense to continue to promote this crop category. Therefore, MASA should particularly promote the diversification to other pulses, besides pigeon pea, with more diversified markets, such as mung beans and common beans. It could also encourage donors and NGOs to focus on these alternative pulses, more so than on pigeon pea, which has already been well-established among farmers.

Editor’s Note: A related blog on this topic can be found here.

[1] The full study, “Pigeon Pea Value Chain Analysis in Mozambique: Public Policy and Action Plan”, will be published in December 2017.