Anticipating regional integration in Africa

The Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) for eastern and southern Africa offers enormous potential for East African Community (EAC) states, but it also poses a staggering organisational challenge

The Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) for eastern and southern Africa offers enormous potential for East African Community (EAC) states, but it also poses a staggering organisational challenge

Regional integration – ceding some national interests in trade policy for the long term purpose of higher growth and improved livelihoods for citizens – is being embraced by countries around the world. As part of this movement, Ministers from 26 African countries and three Regional Economic Communities (RECs) have been discussing the formation of the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA), with an action plan released by the African Union calling for a continental customs union to be formed in 2019. However, in the tradition of many similar integration efforts, the expected December TFTA launch has now been postponed until February 2015.

Establishing ‘deep integration’

Establishing the ‘deep integration’ necessary to the customs union’s success first requires basic trade liberalisation, followed by what Melo and Tsikata call ‘trade facilitation’, facilitated by regionally shared infrastructure as well as common institutions of business practices and standards. The experience of the East African Community (EAC), a customs union with only five members, brings to light some of the details of reform that, if left unaddressed, can greatly delay deeper integration.

The most recent EAC integration efforts began over a decade ago. The EAC Customs Union launched in 2005 with the ‘Big 3’, Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, and later expanded, adding Rwanda and Burundi in 2009. Officially, internal tariffs were removed, and a 3 band (0%, 10%, and 25%) common external tariff was applied starting 2010.

Compromise has been challenging, and the EAC has already experienced a close call. At the end of September 2014, the EAC failed to ratify its pending Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) with the EU. Thus Kenya temporarily lost its duty-free-quota-free (DFQF) access. The least developed country status of the remaining four EAC members – Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi – guaranteed them DFQF status under the EU’s Everything but Arms regime.

Fortunately for Kenya, the venture came through on the 16th of October, when the EAC and EU initialled a region-to-region agreement. Kenya regained DFDQ access, while its EAC partners effectively gained nothing except the obligation to eventually liberalize rates on 80% of EU imports. Melo and Regolo attribute this compromise to a high prioritisation of REC integration. Meanwhile, lingering trade frictions in the EAC indicate the influence of a strong Kenyan negotiating team in the EPA process, and that, rather than universally prioritising integration, members continue to pursue individual interests.

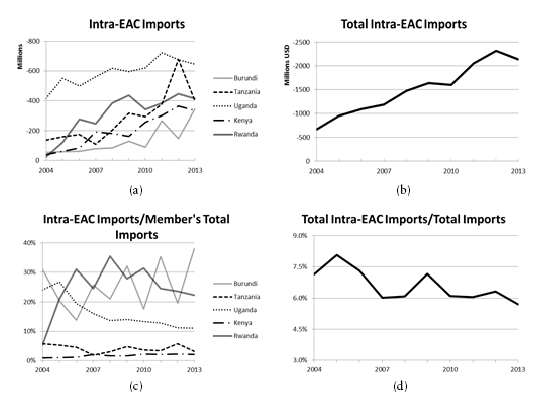

Figure 1: Intra-regional imports have increased but lag behind total imports

Figure 1: Intra-EAC imports, by member state and as a region. Source: EAC Facts and Figures, 2014.

While intra-regional imports have increased, as seen in Figure 1, they lag behind total imports. Specifically, regional import volumes have declined from 8% of the region’s total imports in 2005 to under 6% in 2013. To add perspective, intra-regional trade volumes for EU and NAFTA were around 65% and 45%, respectively, of those regions’ total trade in 2011.

Deep integration is hindered by a range of factors that include: rules of origin; non-tariff barriers such as roadblocks and complex licensing regimes; and deficient transportation infrastructure. Additionally, EAC regulations have potential loopholes and discretionary options to help mitigate perceived adverse effects on local economies.

As TFTA activities progress, the EAC has a limited window of time to determine the standards to promote within the larger 26-member group. EAC reform leaders should push for improved enforcement and accelerated reforms across the EAC in order to present a credible platform. They should leverage moments like the EPA negotiations to advance their position.

Rules of origin and certificates of origin

Any final goods produced within the EAC face limits on imported inputs and must meet a minimum value-added criterion. Specifically, for goods not entirely originating in EAC states, EAC rules of origin require that:

1. Such goods have a cost, insurance, and freight (CIF) value comprised of no more than 60% of imported materials

2. The value added is at minimum 35% of ex-factory costs

or

3. Final goods are transformed enough to list under a separate tariff from any imported inputs

Although the rules of origin seem simple, enforcing them has been hampered by coordination problems at the borders, where certificates of origin have not been sufficiently harmonised and account for an estimated one fourth of the EAC’s non-tariff barriers complaints. The East African Community Market Scorecard, compiled by the World Bank and the EAC Secretariat shows that Tanzania had the highest share of reported problems related to certificates (50%), followed by Uganda (30%), and Kenya and Rwanda (10% each).

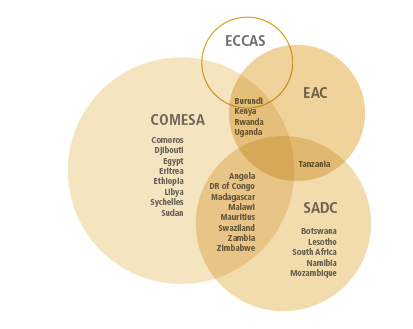

Simplifying rules of origin should be aggressively pursued before fully joining the TFTA — which will require additional harmonisation across the now 26 states — so that the EAC has a more cohesive negotiating position. The EAC could potentially coordinate with the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), as the two rules of origin regimes are currently similar. The larger bloc could then exert pressure against the stricter regime in the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Figure 2: EAC partner states’ membership in free trade areas

Non-tariff barriers

Several administrative and legal requirements likewise increase time and trade costs. According to the Scorecard, Tanzania has the most non-tariff barriers (18), followed by Kenya (16), Uganda (9), Rwanda (5), and then Burundi (3). Before arriving at EAC borders, traders must navigate a series of agencies and obtain the necessary transport permits, an inconvenience exacerbated when agencies are not located near customs posts. Furthermore, the EAC currently lacks harmonised certification procedures, license systems, and any preferential treatment of EAC-based traders.

Despite the 2011 launch of a time-bound programme to eliminate internal non-tariff barriers, their persistence, and the emergence of new non-tariff barriers demonstrate the challenge of their removal. The Scorecard’s analysis found sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures to be the most enduring, comprising about 30% of reported non-tariff barriers, while extra taxes and fees account for almost 20% of reported non-tariff barriers. Promoting the benefits of TFTA membership at home will be easier if EAC traders can expect limited non-tariff barriers in the TFTA. Advocating such an environment will be easier if the EAC can show that its members impose limited or zero non-tariff barriers.

Provisions for exceptions

The EAC CU Protocol includes two mechanisms to grant members flexibility in the face of negative impacts of the CET. A “stay of application scheme” allows Members to effectively suspend the common external tariff temporarily, while a “duty remission scheme” awards exemptions to applicant firms on an individual basis.

The World Bank/EAC Scorecard analysis reported that stay of applications have not affected trade significantly. However, as duty remission is currently awarded to firms on a case by case basis, this provision creates opportunities for corruption and favouritism. Secondly, duty remissions have been applied in ways that depart from the underlying principles of regional integration. For example, the FAO has cited how Kenya has used this provision to open its rice market to Pakistan, in exchange for market access for Kenyan tea exports in Pakistan. Again, these potential loopholes can be exponentially more complex across 26 states if the EAC sends a signal that such behaviour is permissible.

Opportunity for leadership

The Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) offers enormous market potential for East African Community (EAC) states as well as a staggering organisational challenge. The EAC’s strongest position in TFTA will be as a group and should be used to argue for reforms and market practices that best reflect and complement the EAC’s current policy trajectory. The credible force of these arguments can only be strengthened by greater practical enforcement of the overarching EAC trade legislation.