Challenges and opportunities for e-waste in Rwanda

Growth in use and obsolescence of electronic goods results in e-waste which poses significant health and environmental risks, requiring wide-ranging solutions.

There is a sustained global increase in the manufacturing, demand, and usage of electronics and electronic equipment. Simultaneously, the resulting electronic waste (e-waste) generated from obsolete and discarded equipment has risen, bearing significant health and environmental risks. For instance, leaching of heavy metals from e-waste has been found to contaminate the soil and underground water, making land unsuitable for growing crops and water unsafe for drinking. In terms of volume and environmental impact, e-waste is one of the fastest growing waste streamsin the world.

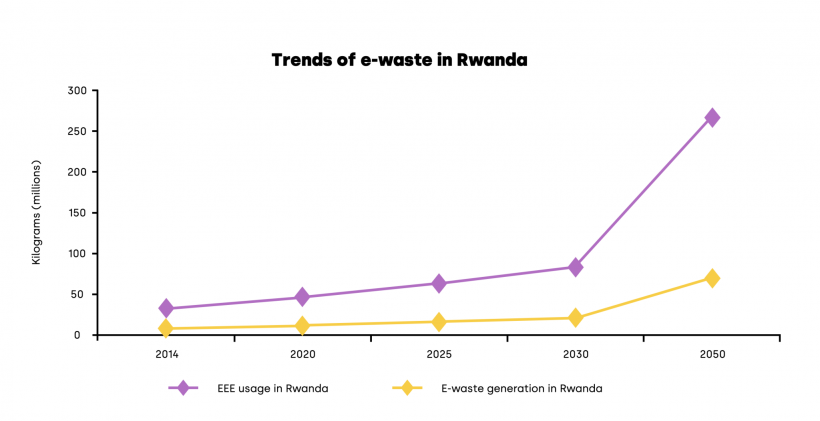

In keeping with global trends, Rwanda has a growing stock of electronic devices and equipment as well as the resultant e-waste. It is estimated that between 2010 and 2014, ICT equipment imports increased by 5% while electronic and electrical equipment (EEE) imports had an estimated 5.9% annual growth rate , resulting in the potential generation of 9,417 tonnes of e-waste per year. Out of this, 81.5% was contributed by individuals, 12.1%by public institutions, and 6.3% by private institutions. In 2014, 8,790 tonnesof e-waste was generated from 33,450 tonnes of EEE while in 2020, 12,432 tonnes of e-waste was generated from 47,309 tonnes of EEE. If this trend continues, it is estimated that by 2025, 16,597 tonnes of e-waste will be generated from 63,155 tonnes of EEE, growing to 22,155 and 70360 tonnesof e-waste from 84,308, and 26,7741 tonnes of EEE in 2030 and 2050 respectively. This is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Trends of e-waste generation in Rwanda

Note: The graph plots previous, current, and estimated trends of e-waste generation with corresponding EEE usage in Rwanda. Both EEE and e-waste have increased gradually over the years and are set to spike and rise sharply by 2030.

Source: Adapted from Twagirayezu et al. 2021.

High demand for EEE, but little awareness of e-waste

The proliferation of EEE and subsequent e-waste has been driven by the increasingly central role of ICT in socioeconomic and population growth as well as the expeditious development of the electronics sector. These factors have led to the substantial accumulation of EEE by institutions and individuals. However, with limited e-waste management facilities in Rwanda, this typically results in environmentally unfriendly disposal of EEE. Although waste dealers collect and dispose of waste at assigned sites, no distinction is made for e-waste which requires separate handling. In addition, despite residents being required to pay for all other waste compilation and disposal, there are currently no special requirements for e-waste which is subsequently treated like all other waste. There is inadequate understanding of e-waste in Rwanda with little knowledge of the risks, potential toxicity, requisite management, and appropriate disposal practices. This leads to e-waste being kept within homes giving rise to very low e-waste streams.

Rwanda’s policy response to e-waste

Rwanda has taken some steps to combat e-waste. The government entered into a public private partnership (PPP) with a private company – Enviroserve – to facilitate the collection and disposal of e-waste. In this agreement, the government provided capital investment through the green fund to build a recycling plant with Enviroserve who were responsible for managing operations and upgrades. In addition to contributing to the green agenda, the PPP has contributed to the creation of ‘green jobs’ through its operations. Between 2017 and 2019, 120 tonnes of e-waste was collected and treated. This in turn contributed to mitigating the equivalent of 270 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions. However, as of 2021, the plant was reported to only run at 30% of the 10,000 tonnes per year capacity raising efficiency concerns. Low utilisation is partly attributable to the low number of collection points (only 20 as of 2021) which negatively impacts access by some parts of the population and therefore collection.

To complement the work of Enviroserve and encourage e-waste recycling, the Ministries of ICT, Environment and other stakeholders have engaged in information sharing on proper e-waste management. Knowledge of the potential toxicity of e-waste has been shown to spur e-waste recycling. However, knowledge campaigns in Rwanda have been sporadic, potentially undermining their intended goal.

Make recycling easier for consumers

One option to overcome the impact of few collection points, is to build on existing waste collection infrastructure and make e-waste recycling easier for consumers. For example, provision of complementary services such as separate containers or bins for e-waste with the existing curb side waste collection service can help increase the quantity of the e-waste collected and recycled.

Apart from establishing adequate infrastructure and systems, there is a need to identify and employ appropriate incentives for consumer participation in e-waste management and recycling. Reducing costs of consumer participation has been shown to positively impact participation in e-waste recycling. Services like a subsidised waste collection fee for separating waste have the potential to incentivise participation. Similarly, providing curbside collection removes the cost of travelling to a central e-waste collection point thereby reducing cost barriers to e-waste recycling.

Extended Producer Responsibility Schemes (EPRs)

Requiring manufacturers to take responsibility for the post-consumer phase of some items has been widely adopted by governments in developed countries. However, the same is not true for developing countries. Extended Producer Responsibility schemes allow for the sharing of responsibility across different stakeholders. Although in Rwanda the majority of EEE purchases are not directly from manufacturers, models that work with suppliers and importers can be put in place to implement EPRs. Examples of EPR models include economic and market-based instruments that incentivise the implementation of environmental protection frameworks such as deposit refund schemes and disposal fees on EEEs

Urban mining from e-wate recycling

The extraction of precious metals from e-waste provides a major opportunity for the development of a vertical e-waste recycling industry. Domestically extracting precious minerals from e-waste and undertaking domestic value-addition (rather than exporting for value addition) cannot only preserve resources and control pollution but it can also create jobs. This however, would require large investments from both the public and private sector in part because of the presence of hazardous chemicals that require advanced recycling techniques.

E-waste and its improper disposal can adversely impact the environment and human health in Rwanda. Dealing with these challenges requires a coordinated effort from the public and private sectors; increased awareness of e-waste; and reduced costs for participation in e-waste recycling. In addition, sharing responsibility of e-waste management with manufacturers, suppliers and importers can have positive implications for the environment and the health of current and future generations.

To learn more about the climate priorities in developing countries discussed during the LSE Environment Week view the policy memos tabled and other recordings here and read IGC’s latest growth brief on sustainable growth for a changing climate.