How do people value air quality?

Phasing out coal-fired power is key to mitigate climate change. However, fast-growing nations such as India and China still invest heavily in coal as an energy source. Popular pressure could revert this situation, but it is not clear whether those who reside near coal plants are aware of their negative consequences.

Phasing out coal-fired power, replacing it with less polluting alternatives, such as wind and solar, is one of the key forms of climate action that governments around the world could undertake to mitigate climate change and environmental damage. Renewable technologies are now sufficiently scalable to replace much of the capacity generation of coal-fired power plants. Also, fast-growing R&D investments in energy storage technology are helping address the challenge of variable grid demand. Thus, a green energy transition looks technologically more feasible now than ever.

To achieve this from the bottom up, there needs to be pressure from the citizens of coal power-dependent countries. In this spirit, most of the coal power plants in the United States and in Western European countries have been scheduled for retirement. However, coal power generation still commands strong public and private investments in fast-growing nations such as India and China. Coal is a highly polluting energy source, with detrimental consequences for both air quality and climate change. But it is still far from obvious that those who reside near coal-fired power plants are aware of its negative consequences. And, if that is not the case, political forces seem less likely to be unleashed.

Does being near coal-fired power stations increase concerns about air quality?

In our research, we investigate whether perceptions of air quality are affected by proximity to operational coal-fired power stations. To do this, we make use of global attitudes data on ambient air quality perceptions from the Gallup World Poll, a nationally representative annual survey covering 99% of the world’s adult population living in more than 160 countries. We focus on measuring local effects by exploiting spatial granularity at the geocode level (that is, latitudes and longitudes of survey respondents). We are therefore able to detect whether respondents are located within 40 km of a coal power plant. The main analysis is representative of 51 countries, which are mostly low- and middle-income.

We use these findings to construct a measure of the willingness to pay for closing existing coal-fired power plants in all the 51 countries. To do so, we look at the life satisfaction approach (following earlier work by Layard, Mayraz and Nickell, 2008; Kahneman and Deaton, 2010). This exploits the negative relationship between air quality dissatisfaction and life satisfaction along with the positive relationship between income and life satisfaction to get an “income equivalent” to air quality dissatisfaction. We use these numbers to estimate the net benefits of transitioning towards solar and wind generation on a global scale. Considering only the resulting air quality improvements, the benefits are large enough to justify investing in a green transition that involves closing coal fired power stations.

Studying low- and middle-income countries

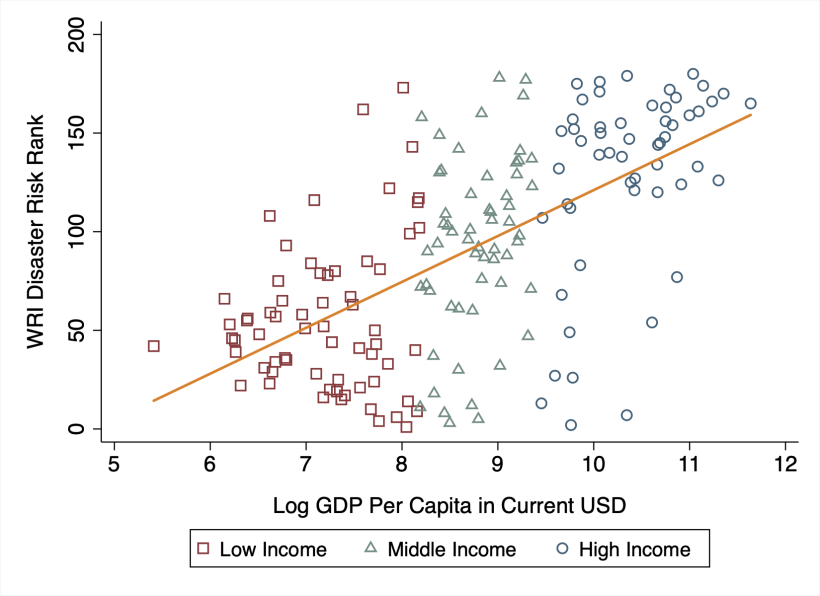

Much of the prior research on climate change within environmental psychology has concentrated on high-income, primarily the United States and Europe. However, climate change damages are predicted to be disproportionately higher in low- and middle-income countries. Moreover, future energy demand is predicted to come from the countries that continue to rely heavily on coal. There is a need to close this knowledge gap by looking at low- and middle-income countries, something that our work does. Figure 1 suggests that low- and middle-income countries are placed at lower values in ranking, thereby are at higher risk of disasters unfolding due to climate change.

Figure 1: Relationship between country-level disaster risk and GDP per capita

Notes: This chart presents a scatterplot of the WRI country-level disaster risk rankings and country-level GDP per capita in 2019. Rankings are in decreasing order, that is, countries in the lower ranks are at higher risk of damages caused by disaster events. The ranking considers countries’ exposure, vulnerability, susceptibility, coping capability, and adaptive capacity.

Linking location and perceptions

Domestic and international policies to reduce carbon emissions are only likely to happen in democracies if citizens demand change. Hence, it is crucial to know about the factors that drive citizens’ perceptions of their local environment. We find that there is a positive relationship between living near a coal-fired power station and dissatisfaction with ambient air quality. This is important because it suggests a latent demand for policy change.

Estimating willingness to pay for clean air

Scientific evidence has championed concerns about the detrimental effects of coal power. But there are people who benefit from the status quo through employment opportunities both directly in the plants and indirectly in coal mining and associated activities. Shutting down coal plants or replacing them with renewables would have distributive effects. Looking at these distributional consequences is an important topic for further research.

Looking at perceptions of air quality, we can gain some insight into how people value air quality and hence what would be the implicit willingness to pay for moving away from coal-fired power. Of course, this does not mean that people will pay in practice, but we can still calibrate how perceptions of air quality affects wellbeing, and hence how it compares to the effect of income on wellbeing.

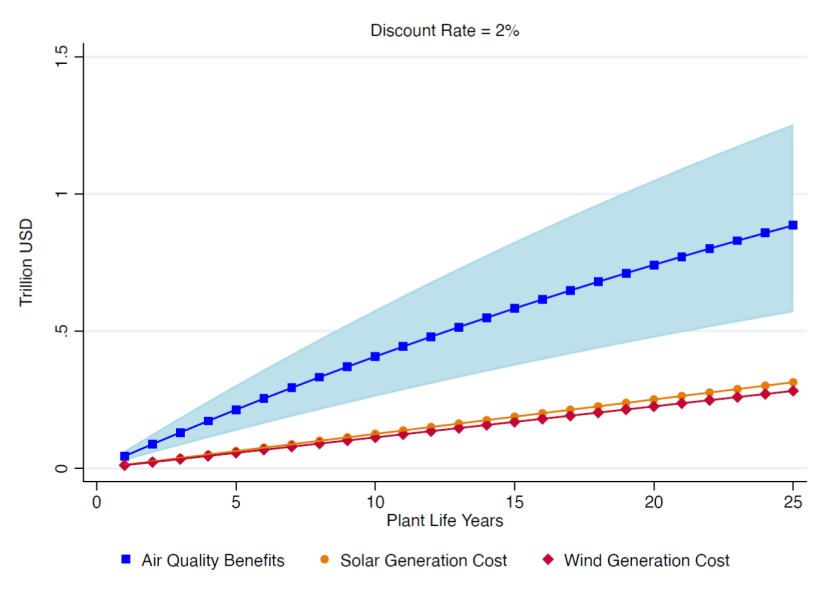

Using the quantitative relationship between the wellbeing indicator, which is measured on a 10-step Cantril ladder, and income and air quality dissatisfaction level, we estimate the equivalent variation of moving residents in the 0-40 km distance band to outside that band with better air quality. We use this to see whether transition from coal-fired power to green energy is feasible, given the benefits and the costs. As shown in Figure 2, the transition looks feasible even if we take a very cautious view on the estimates of benefits that come from air quality enhancements from closing coal plants. And we could look at this for different countries across the world and across education groups.

Figure 2: Air quality improvements cost-benefit analysis

Notes: The chart shows the cost-benefit results for all 51 countries combined. The policy experiment entails phasing out coal-fired power at a constant rate of 4% per year and replacing that freed capacity with solar or wind generation over a period of 25 years. The blue line represents point estimates of air quality benefits with the shaded area showing upper and lower bounds on the estimates. The costs of solar and wind energy generation are calculated by multiplying their respective source-specific average global LCOE values in USD/kWh with the total excess energy demand because of closing of coal plants.

Looking at differences in our measure of willingness to pay across education groups, the educated elite group stands out; being nearly two to three times of other education groups. In terms of differences across space, we estimate that Indians are less concerned on average. It can be argued that given India is a middle-income country, income might yield greater life satisfaction than air quality to its citizens.

In practice, the decisions that policymakers will have to make to bring about a green transition will involve deciding whether to decommission specific coal-fired power plants.

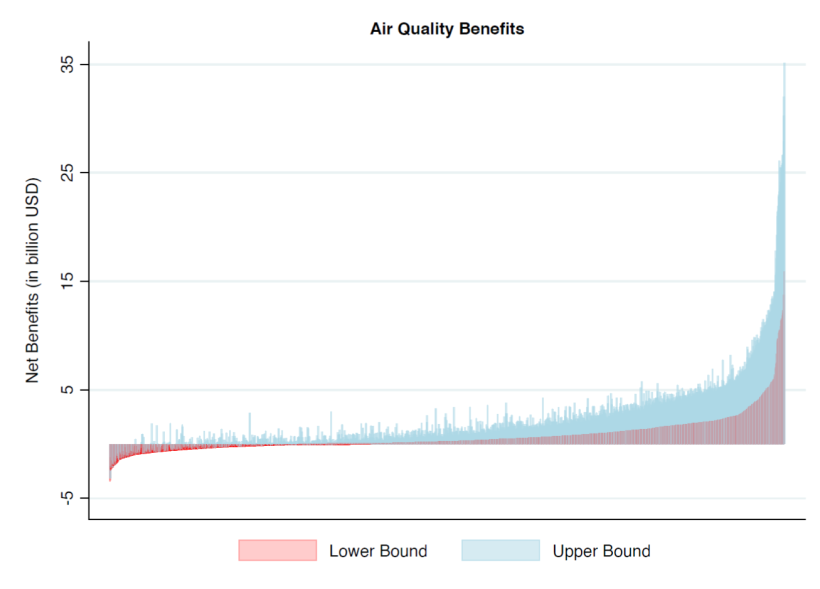

Our analysis allows us to look at a policy strategy of that kind by looking at the benefits of closing specific coal-fired power stations. Figure 3 gives the plant-level net benefits for all operational coal-fired power plants across the world in 2019. It gives a good sense of the distribution of benefits and makes it clear that replacing coal plants with solar and wind generation units would be beneficial in almost all cases, even if we take a very cautious view on the estimates of net air quality benefits.

Figure 3: Plant-level net benefits from closing all coal-fired power plants

Notes: The chart shows the net benefits from closing all the operational coal-fired power in 2019 located across the whole world. The parameter values are taken from the global estimates using all the 51 countries combined. The policy experiment entails phasing out coal-fired power and replacing that freed capacity with 50% solar and 50% wind generation. The two shaded regions in both plots represent upper and lower bounds of the benefits estimates. The costs of solar and wind energy generation are calculated by multiplying respective source-specific global average LCOE values in USD/kWh with the total excess energy demand because of shutting down coal plants.

This article was first published in the LSE Business Review.