Closing the gender profit gap through savings and training: Evidence from Mozambique

Access to mobile savings accounts and financial management skills can lead to improved profits and financial security of female-led micro-enterprises

The ILO estimates that 78% of the world’s poor living in low-income countries are self-employed (ILO 2017). Yet female-led microenterprises often struggle with low levels of growth and rates of survival. Indeed, a salient fact about self-employment is the persistence of a substantial business performance gap between male and female microentrepreneurs (Nix et al. 2015, Morgan and Kagy 2018). Female-led businesses often report less than half of business profits, even when they operate in similar sectors as their male counterparts (Morgan and Kagy 2018).

Our study (Batista, Sequeira and Vicente 2021) focuses on two key supply-side constraints to female-led business performance that can contribute to this gender profit gap: limited access to capital (Bruhn and Love 2009, Collins et al. 2009, de Mel et al 2010) and lack of exposure to financial management know-how (Rosenthal and Strange 2012, Field et al. 2016, McKenzie and Woodruff 2017, McKenzie, 2020).

Existing evidence for improving supply-side constraints is mixed

Increased savings can play a critical role in helping low-income microentrepreneurs optimise their cash flow management, their investment strategies, and improve the performance of their business. However, female microentrepreneurs often have limited access to savings technology due to restricted mobility, a higher opportunity cost of time, and lower levels of financial literacy—all of which constrain their interaction with the traditional banking system. In this context, the evidence on how savings can impact microenterprise performance in practice is still mixed (Dupas and Robinson 2013, Schaner 2018).

In settings of poor human capital and limited exposure to entrepreneurial know-how, financial management training can potentially improve financial practices that allow for higher savings, better forecasting of revenues and expenses, improved inventory management and, as a result, improved firm performance. But business training programmes have shown sometimes positive (Klinger and Schuelden 2011, Field et al. 2016, McKenzie and Puerto 2020) and sometimes negative or zero effects in a variety of contexts (Karlan and Valdivia 2010, Drexler et al. 2014).

While mobile money accounts can significantly reduce the cost of keeping and accessing safe savings, they can also reduce the cost of these savings being dissipated in the form of transfers to family or other non-income generating types of consumption. These effects can be exacerbated for female microentrepreneurs who tend to lack access to traditional banking and who may be more heavily taxed by their relatives, including by their husbands (Fafchamps et al. 2014, Bernhardt et al. 2019 and Solene et Ng 2020).

Moreover, increased savings may not translate into improved business performance if female microentrepreneurs lack the ability to manage resources well (de Mel et al 2010, Dupas and Robinson 2013, Bernhardt et al. 2019). Similarly, improved financial literacy and management capabilities may not translate into improved business performance if microentrepreneurs have limited financial resources to invest towards business growth (Klinger and Schuelden 2011, Schaner 2018).

One potential reason for these mixed results is that releasing only one of these constraints may not be enough to improve business performance and investment for future business growth.

Research methodology

To test the independent effect and complementarity between these interventions, we take advantage of the rollout of mobile money in Mozambique to create mobile money accounts with a temporary (three months) but high-powered incentive to save (a 5% interest rate). We then design a business management training course, with a particular emphasis on separating household and business accounts, cash flow management, bookkeeping and the implications of transfers to relatives. This course was delivered across four one-hour, in-person, training modules, and followed a standard rules-of-thumb approach (Drexler et al. 2010), relying heavily on visual illustrations and examples from everyday market situations to ensure participants understood how to apply the training to their day-to-day business activities.

We randomly assigned 1,270 microentrepreneurs operating in services and retail into the three treatment arms:

- access to mobile money accounts and high-powered but short-term (three months) incentives to save;

- financial management skills training; or

- a combination of both treatments.

A fourth group served as a control and did not receive any intervention.

The sample was stratified by the gender of the microentrepreneur where we benchmark treatment effects against the impact of the same interventions in a cohort of male microentrepreneurs. This design also allows us to examine how the interventions affect the gender profit gap by comparing the business performance of treated female microentrepreneurs with that of control male microentrepreneurs at endline.

Our outcomes of interest, namely profits and financial security of the microentrepreneur, were assessed at baseline, 12 months later, and then again six years after the intervention.

Impact on profits and financial security for female microentrepreneurs

Twelve months following the interventions, the combined treatment led to a significant increase in profits for female microentrepreneurs. Both the combined treatment and the mobile money treatment are also associated with higher levels of household financial security (a 7% increase relative to the control mean). This is measured through an index capturing whether in the last 12 months, anyone in the household went without food, and if the microentrepreneur was able to pay for children’s schooling expenses. The effect on profits persists and grows in the following five years, representing a doubling of profits for the joint treatment group relative to the control.

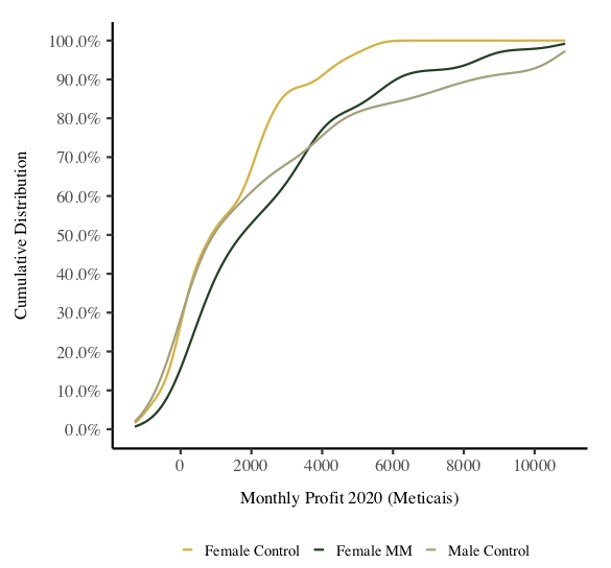

In the long-run, the mobile money treatment also increased firm profits, but mostly for female microentrepreneurs who started off with lower performance.

Gender-specific impacts

We then examine the impact of these interventions on a matched subsample of male and female microentrepreneurs who are more similar on observable characteristics including store characteristics, experience, assets, sales at baseline and financial literacy.

In this matched sample, the mobile money treatment no longer has an effect on long-run profits, while the treatment effect for the combined intervention is still sizable and significant. These findings suggest that providing access to liquid savings through mobile money is effective mostly for female microentrepreneurs who have lower levels of profit to begin with. Once we account for these differences across male and female microentrepreneurs in the matched sample, the mobile money intervention alone no longer increases profits.

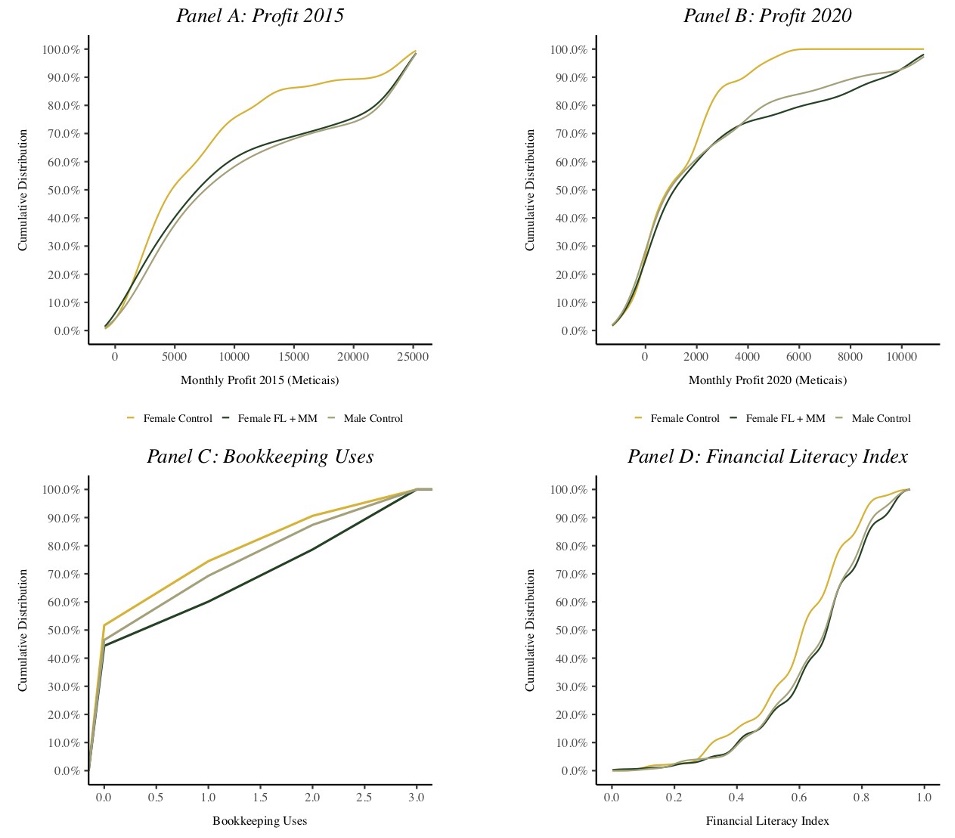

Only the combined treatment allows female microentrepreneurs to close the profit gap, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 Closing of the performance and knowledge gap between treated female microentrepreneurs and control male nicroentrepreneurs at endline, for the combined treatment of mobile money and business management training

Figure 2 Partial closing of the profit gap by 2020 for those in the mobile money savings group

The key mechanisms behind these treatment effects were a sustained improvement in financial management knowledge and practices such as bookkeeping, lower remittances, and higher savings in more liquid and potentially safer mobile money accounts. Mobile money accounts were used primarily to store money and make remote payments for critical utilities such as electricity.

Male microentrepreneurs learn from our financial management training programme and they improve their bookkeeping practices. They also take up the mobile money service but they are less likely to report replacing traditional bank savings with mobile money savings. Despite these positive effects associated with the intervention, we observe no real changes in profits or financial security suggesting that our interventions did not address the binding constraints to growth for male-led microenterprises.

Conclusions

We provide novel evidence on an important complementarity between providing female-led microenterprises with the enabling technology to build their savings, while at the same time providing financial management skills with a special focus on how these savings can be applied to maximise business returns.

When targeted to female microentrepreneurs, these interventions can have a positive, significant, sizable, and long-lasting effect on profits and the financial security of female micro-entrepreneurs. This enables them to close the gap in knowledge and business performance relative to their male counterparts. Specifically, for female microentrepreneurs with lower levels of profits, savings, and skill, just providing access to mobile money accounts that encourage savings appears to have a positive impact on long-term profits—leading to a partial closing of the gender profit gap for this subset of microentrepreneurs alone. The main mechanisms behind these effects are improved financial management practices (bookkeeping), reduced transfers to relatives, and increased savings.

This article first appeared on VoxDev (you can see the original here)

References

Batista C, S Sequeira and P Vicente (2021), “Closing the Gender Profit Gap”, Working Paper.

Bernhardt, A E Field, N Rigol and R Pande (2019), “Household Matters: Revisiting the Returns to Capital among Female microentrepreneurs”, American Economic Review: Insights 1(2).

Bloom, N, A Mahajan, D McKenzie and J Roberts (2010), “Why Do Firms in Developing Countries Have Low Productivity?”, The American Economic Review 100(2): 619-623.

Bruhn, M and L Inessa (2009), “The Economic Impact of Banking the Unbanked: Evidence from Mexico”, Policy Research working paper; no. WPS 4981. World Bank.

Collins, D, J Morduch, S Rutherford, and O Ruthven. (2009), Portfolios of the Poor, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

de Mel, S, D McKenzie and C Woodruff (2008), “Returns to Capital in Microenterprises: Evidence from a Field Experiment”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(4): 1329-1372.

Drexler, A, G Fischer and ASchoar (2014), “Keeping it simple: Financial Literacy and Rules of Thumb”, American Economic Journal. Applied Economics 6(2): 1-31.

Dupas, P and J Robinson (2013), “Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya”, American Economic Journal. Applied Economics 5(1): 163-192.

Dupas, P, D Karlan, J Robinson, and D Ubfal (2018), “Banking the Unbanked? Evidence from Three Countries”, American Economic Journal. Applied Economics 10(2): 257-297.

Field, Er, S Jayachandran, R Pande and N Rigol (2016), “Friendship at work: Can peer effects female entrepreneurship?”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 8(2): 125:53

Hardy, M and G Kagy (2018), “Mind The (Profit) Gap: Why Are Female Enterprise Owners Earning Less Than Men?”, American Economic Association, Papers and Proceedings 108: 252-55

Karlan, D and M Valdivia (2011), “Teaching entrepreneurship”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 93(2): 510-527.

Klinger, B and M Schundel (2011), “Can Entrepreneurial Activity be Taught? Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Central America”, World Development 39(9): 1592-1610.

McKenzie, D and A L Paffhausen (2019), “Small Firm Death in Developing Countries”, Review of Economics and Statistics 101(4): 645-57, 2019

McKenzie, D and C Woodruff (2017), “Business Practices in Small Firms in Developing Countries”, Management Science 63(9): 2967-81.

McKenzie, D and S Puerto. (2020), “Growing Markets through Business Training for Female Entrepreneurs: A Market-Level Randomized Experiment in Kenya”, American Economic Journal. Applied Economics, forthcoming.

McKenzie, D (2020), “Small Business Training to Improve Management Practices in Developing Countries: Reassessing the Evidence for ’Training Doesn’t Work”, Policy Research Working Paper; No. 9408. World Bank

Nix, E, E Gamberoni, and R Heath (2015), “Bridging the Gender Gap: Identifying What Is Holding Self-Employed Women Back in Ghana, Rwanda, Tanzania, and the Republic of Congo”, World Bank Economic Review 30(3): 501-512

Rosenthal, S and Wi C Strange (2012), “Female Entrepreneurship, agglomeration and a new spatial mismatch”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 94(3): 764-788.

Schaner, S (2018), “The persistent power of behavioral change: Long-run impacts of temporary savings subsidies for the poor”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10(3): 67.