What prevents women’s labour force participation in Pakistan?

Social norms may not matter so much for certain groups such as well-educated managers of relatively large firms. Despite this perceived gender neutrality, women employees only make up a small fraction of the total workforce in Pakistan’s garment manufacturing industry.

Pakistan’s female labour force participation (FLFP) substantially lags behind the rest of the world and its neighboring countries in South Asia. In 2019, the country’s FLFP rate for women aged 15 to 64 was 22.6%, which is significantly lower than the world average of 52.6% and even low compared to the South Asian average of 25.2%. The social norms of physical gender segregation, prevalent in some Islamic countries, makes entering the formal labour market difficult for Pakistani women, but they can also affect Pakistani employers’ decisions to hire women, as demonstrated in the recent studies in Saudi Arabia by Miller et al. (2019) and Eger et al. (2022).

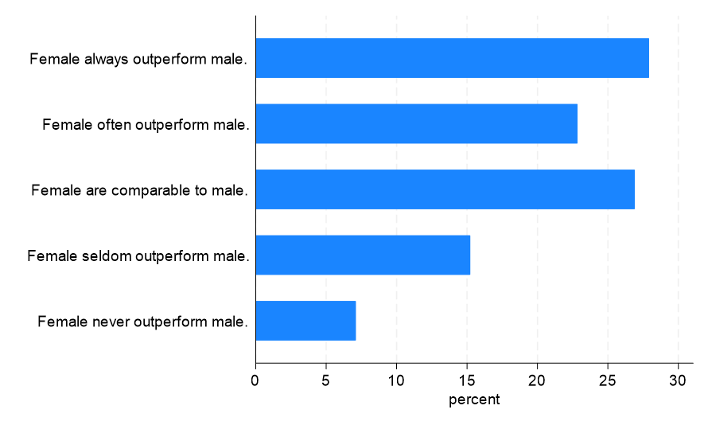

Even in this milieu with norms unfavourable towards formal female employment, some Pakistani employers are seemingly willing to hire women, and consider women viable job candidates. Our survey of garment manufacturing firms in the Punjab province of Pakistan shows that 74% of the interviewed employers think women are at least as good as, if not better, than men at on-site production jobs (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Employers' perception of relative female job performance

With which of the statements do you most agree, with respect to non-finishing production positions?

Notes: Non-finishing production positions were defined in the survey as factory positions in which people work on tasks such as knitting, dyeing, cutting, embroidery, and stitching. There is no statistically significant correlation between employers’ positive beliefs about women’s relative performance and their social desirability bias.

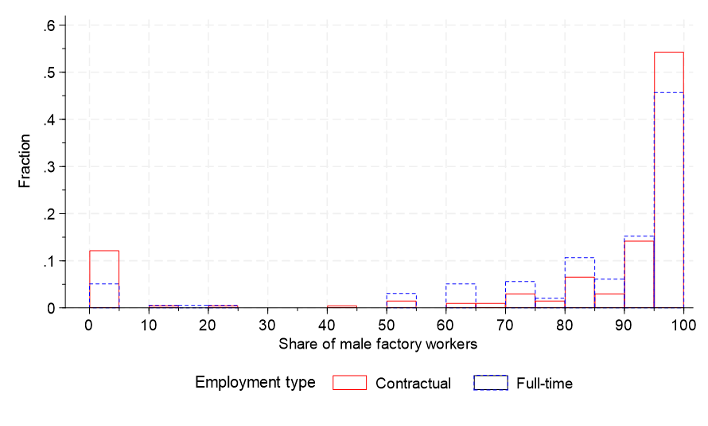

Yet, employers in our sample, as well as those in the greater industry, do not hire women for on-site factory positions in Pakistan. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the share of male workers for factory positions. Nearly 70% of employers fill 90% or more of factory positions with men in our survey sample. Furthermore, the share of female employees in Punjab’s garment manufacturing industry was only 12% in 2011, according to Pakistan’s Census of Manufacturing Industries.

Figure 2: Distribution of share of male workers at factory by employment types

Notes: The majority of the factory positions have gone to male workers, with 70% of employers filling 90% or more factory positions with male workers.

This project investigates this problem by understanding employers’ constraints in hiring women in the context of the garment manufacturing industry in the Punjab province of Pakistan. We examine whether there are economic and non-economic costs associated with employing women. The main goals of this study are to provide evidence on: 1) the presence of economic and non-economic costs in hiring women, 2) whether alleviating the burden of economic integration costs can motivate firms to hire women, and 3) the potential for monetary incentives in influencing the willingness to comply with social norms.

A hypothetical-choice methodology and a behavioural experiment

To answer our research questions, we collected original firm survey data on integration costs in Pakistan using two methodologies: a hypothetical choice and a behavioural experiment. The hypothetical choice method is designed to collect firms’ reported choice probabilities to hire women under different cost environments, which vary on the basis of how all of the five or a subset of these economic costs, faced by the firm, are covered; i.e., through a lottery or by the firm itself.

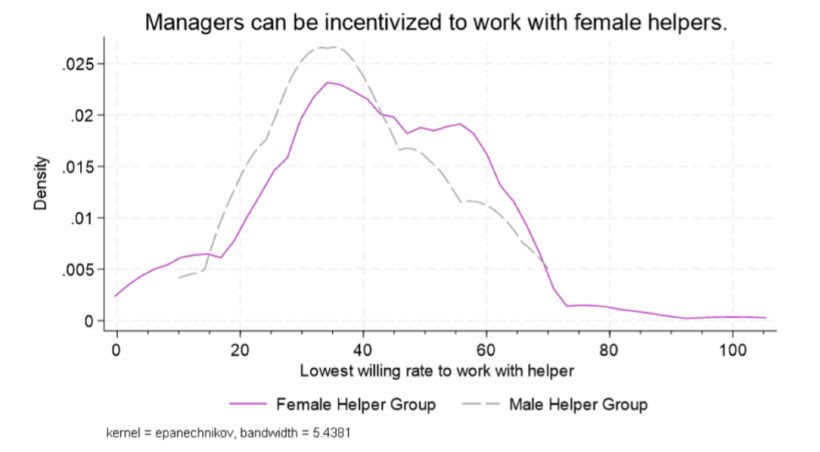

On the other hand, the marble sorting behavioural game (Figure 3) is aimed at measuring the willingness to comply with social norms that idealise strict physical separation of the sexes, using the Becker-Degroot-Marschak (BDM) mechanism. In this game, a top manager is asked to sort marbles for a short period of time for a monetary prize with a helper whose gender is randomly determined. This experiment is designed to produce data on each individual manager’s lowest rate at which he is willing to play this game with the helper. Using the two approaches our project provides evidence on 1) whether there are economic and non-economic costs in hiring women, 2) if relaxing the potential burden of bearing economic integration costs motivates firms to hire women, and 3) whether the willingness to comply with social norms can be monetarily incentivised.

Figure 3: Marble sorting game setup

Notes: Measures the willingness to comply with social norms that idealise strict physical separation of the sexes.

Key findings

- Amongst the surveyed firms, the adherence of top managers to social norms of physical gender segregation is not a significant factor.

Figure 4 presents the results from the marble sorting game experiment and plots the willingness to comply with social norms of gender segregation for the group of top managers who were assigned a female helper. The key takeaways are:

- The mean willingness to comply is PKR 41, which is close to the median.

- While managers have different thresholds at which they are willing to work with the helper, the gender of the helper does not seem to affect their decisions.

- Comparing the distributions of managers’ reported lowest willing rate to work with the helper across the groups of managers who were assigned the female or male helper, we learn that there is no statistically meaningful difference between the means of these groups.

Finally, from the hypothetical choice model, we find that all women-related hiring costs negatively affect the likelihood of hiring women. However, the cost of providing safe transportation to women appears to have the greatest positive impact on employers. This evidence suggests that policymakers interested in increasing female labour force participation in the garment industry should prioritise resource allocation towards decreasing the cost burden of transportation of women.

Figure 4: Willingness to comply with social norms

Notes: The figure plots the willingness to comply with social norms of gender segregation for the group of top managers who were assigned a female helper. While managers have different thresholds at which they are willing to work with the helper, the gender of the helper does not seem to affect their decisions.

- Top managers generally perceive their workers as more open to collaborating with female counterparts, and their willingness to comply for a typical male worker does not exceed their own willingness to comply.

This suggests that, in the given context, traditional norms of physical gender segregation are not deemed crucial. Moreover, the study highlights that the visibility of a typical male worker’s actions is a critical consideration for top managers. Such concerns escalate when male workers’ behaviour towards female workers is not observable.

- The study also points out that other factors, beyond social norms of gender segregation, play a more dominant role in influencing the hiring of women.

Specifically, the cost associated with providing safe transportation for female workers emerges as a key determinant in the decision-making process of firms regarding the employment of women.

Policy implications

- Addressing employers’ economic constraints in hiring women may be more important for increasing female labour force participation than changing social norms for a certain group of employers.

The study has shown that, even in a context where social norms around gender are a dominant part of life, norms may not matter so much for certain groups such as well-educated managers of relatively large firms. However, women are only a small fraction of the total workforce in these firms.

- The cost of providing safe transportation is perceived to be more binding as a cost of hiring women by employers.

While the findings from the current study suggests that assisting firms on the cost of providing safe transportation may encourage firms to hire more women, we believe that a further study that can identify an efficient way to provide such support is necessary. This is in line with the experimental findings provided by Field and Vyborny (2022), which shows that the lack of safe transportation reduces women’s propensity to search for jobs. Our study implies that employers are also constrained in hiring women when they are unable to offer them transportation services.

- Future studies to understand whether current key findings hold amongst smaller firms is necessary.

The current study sample is limited to relatively large companies, while the industry in Pakistan predominantly consists of much smaller firms. An additional study that can understand constraints of hiring women amongst these firms will also be relevant. Furthermore, understanding if social norms hold the same importance for top managers of smaller firms is important before deciding on concrete policy prescription.