Is green growth possible? Revisiting the Environmental Kuznets curve

Can economic growth be environment friendly? IGC Policy Economist, Matei Alexianu, looks at what we can learn from economic theory and evidence from around the world. He argues that both the optimistic and pessimistic views are unconvincing, and developing countries should use environmental policy to mitigate the costs of growth.

Is there a trade-off between economic growth and a clean environment? Today more than ever, this question is crucial not only for economists and policy makers but for us all. We are already experiencing the effects of climate change. The world is 1°C warmer than pre-industrial levels (Met Office, 2015). This year alone, we have witnessed unprecedented droughts in Cape Town, an earthquake and tsunami In Indonesia, forest fires in the Arctic, and devastating hurricanes in the US. The question is not whether climate change needs to be tackled but how. Do we need to re-think our growth strategy?

Can economic growth be sustainable? The current debate

Many experts have weighed in on this question. At one end of the spectrum, the ‘degrowth’ movement argues that further global economic growth is ecologically unsustainable. In response, it advocates for a conscious push to decrease consumption levels – and therefore, GDP. Its proponents point out that a decline in GDP would not necessarily translate into welfare losses, and could even increase living standards, as Jason Hickel argues. But regardless of whether this is true, radically rewiring the global economy in a world where rich countries have historically grown rich through massive consumption at high environmental cost appears a far-fetched prospect.

At the other end of the spectrum are the ‘eco-modernists’ who argue that economic growth and its associated technological improvements enable countries to consume fewer natural resources and mitigate their environmental impact. However, there is little evidence that this has happened so far at the global level – natural resource use is expected to more than double by 2050 and pollution and carbon emissions continue to rise. So for now this strategy requires waiting for new technology to be developed. The potentially devastating costs of further environmental damage due to increasing emissions suggest ‘waiting it out’ is too risky.

What does economic theory tell us?

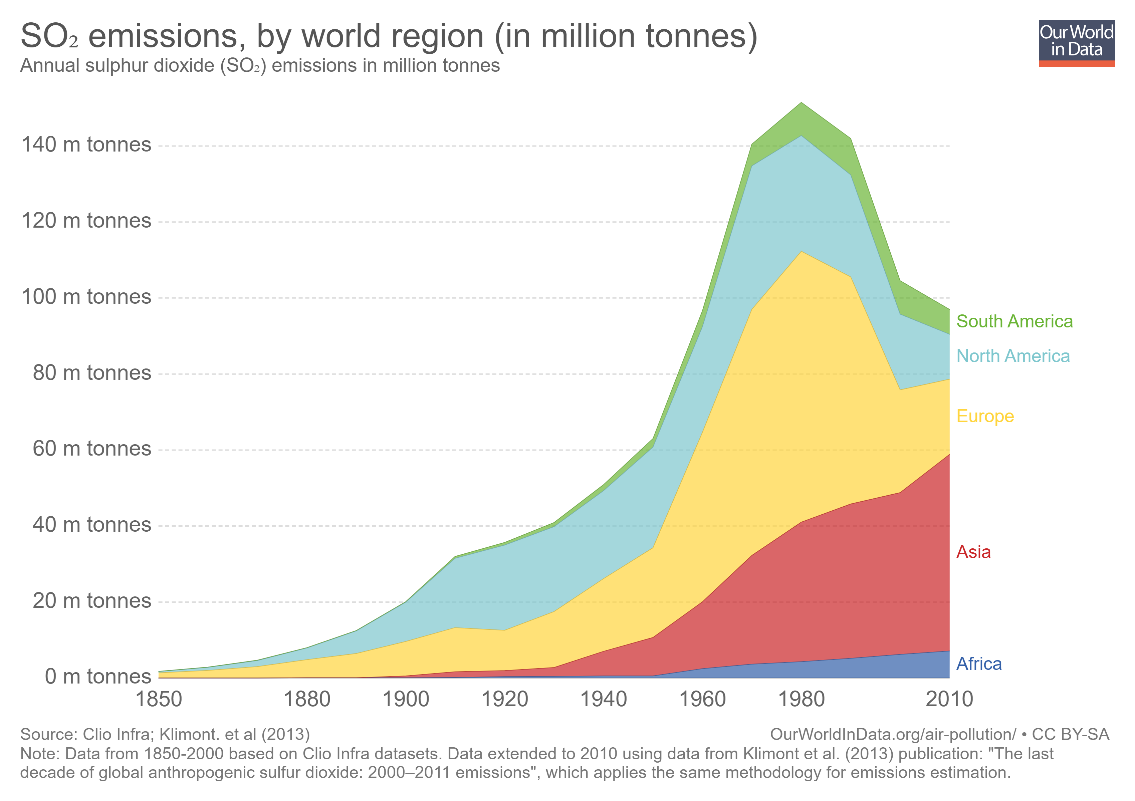

Much of the economic literature suggests a more nuanced picture – at the country level, the ‘Environmental Kuznets Curve’ posits that pollution tends to increase as an economy grows and then, at a certain point, begins to fall. Figure 1 demonstrates that emissions of sulphur dioxide (SO2), a major pollutant, have reduced from 1980 to 2010 in all regions except Africa and Asia, which fits this hypothesis. But while this may sound like good news for developing economies, the evidence remains mixed.

Figure 1: SO2 emissions are increasing in Asia and Africa but decreasing everywhere else

Figure 1: SO2 emissions are increasing in Asia and Africa but decreasing everywhere else

The Environmental Kuznets Curve

One of the most popular economic tools to understand the relationship between growth and the environment is the Environmental Kuznets curve (EKC). The relationship was first introduced by Grossman and Krueger (1991) and popularised by the 1992 World Bank Report on ‘Development and the Environment.’ Its central claim is that environmental damage increases with income until a ‘turning point’ is hit, after which it begins to steadily decline. The resulting U-shaped curve is named after Simon Kuznets (1955) who posited a similar relationship between income inequality and economic growth.

In theory, this trajectory is driven by three countervailing effects:

- Scale effect: Pollution increases in line with economic output if technology and the structure of the economy remain unchanged.

- Composition effect: Pollution may either increase or decrease with economic output as certain sectors of the economy grow relative to others.

- Technique effect: Pollution is likely to decrease with economic output as technology makes production less pollution-intensive and/or citizens demand a cleaner environment.

The EKC hypothesis posits that the technique and (possibly) composition effects begin to overwhelm the scale effect at a certain level of income. But despite a wealth of studies run to test the hypothesis empirically, the results are mixed.

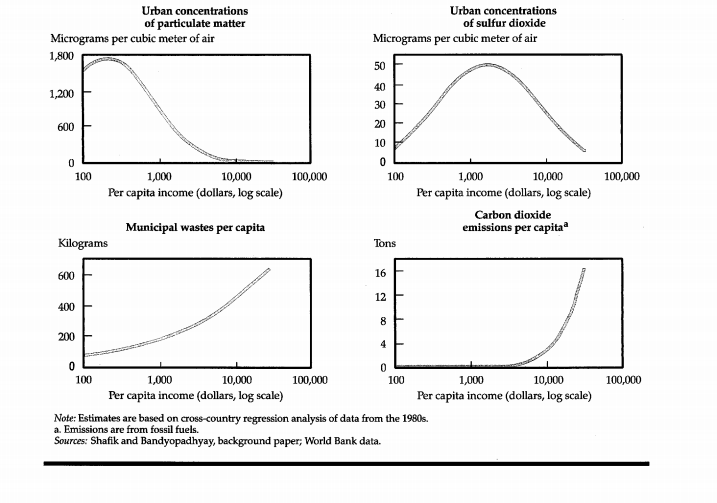

Many studies (Grossman and Krueger 1995, Cole et al. 1997, Stern and Common 2001) do find a turning point for ‘local pollutant’ emissions including nitrogen oxides, sulphur dioxide, and particulates that ranges between $7,300 and $18,000 per capita GDP, but the estimates vary by country.

However, CO2 emissions, among others, are typically found to increase with economic growth. This is possibly because the effects of this ‘global pollutant’ are much more easily externalised to other countries (Shafik 1994), though a very high turning point yet to be observed might also be possible. In short, local pollution does seem to decrease with economic growth after a country reaches a certain level of income but only for some pollutants.

Figure 2: Some initial results supporting an Environmental Kuznets Curve for some pollutants

Figure 2: Some initial results supporting an Environmental Kuznets Curve for some pollutants

EKC and developing countries: A word of warning

Should developing countries only focus on growth since its effects on the environment will take care of themselves over time anyway? This is a bad idea for several reasons:

- The EKC relationship may not hold for developing countries;

- the EKC relationship may not be automatic even if it does hold; and

- the transition growth period before a turning point may well be very unpleasant and trigger potentially irreversible changes to the environment.

- The EKC relationship may not hold for developing countries

As mentioned earlier, the empirical evidence is mixed – particularly regarding ‘global pollutants’ such as CO2 – and in any case, is backward-looking. Extrapolating results into the future is problematic, especially as the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Pessimists point to the ‘pollution haven’ hypothesis, which argues that developed countries have reduced pollution at least in part by offshoring dirty industries to developing countries with less stringent environmental regulations (the composition effect). If true, this would mean that developing countries could not replicate the experience of developed countries, as there would be nowhere left to outsource their own pollution.

However, Levinson (2009) reveals that only around 10% of the clean-up of manufacturing by the US can be explained by offshoring, with the rest being explained by technology improvements (the technique effect). Nevertheless, other studies have found a more significant pollution haven effect, leading Cole and Neumayer (2005) to warn that the EKC represents a ‘best case scenario’ for developing countries.

- The EKC relationship may not be automatic even if it does hold

In particular, the composition effect – that is, consumers choosing to consume cleaner goods as an economy grows – can be broken down into an automatic effect of a change in people’s preferences away from dirty consumption and an indirect effect of changes in prices and regulations.

In a study of US consumption and pollution levels, Levinson and O’Brien (2015) argue that:

- Overall, the technique effect (technology) is the largest driver of the EKC relationship

- Within the composition effect, the indirect component (prices and regulations) accounts for around half of the resulting changes in pollution levels

- This suggests that environmental regulations have an important role in reducing the pollution that comes with economic growth. Policy can stimulate the technique effect by requiring polluters to adopt abatement technologies early.

- Best-case scenario: A painful transition

Even in the best-case scenario, where ‘growing out of pollution’ is automatic for developing countries, the transition period until pollution starts to abate will be long and painful without additional action. Cole and Neumayer (2005) use turning point estimates for preceding studies to forecast pollution levels in developing countries. They find that even in an optimistic growth scenario, Africa will see most types of pollution increase until after 2100.

Considering the already high levels of pollution in developing regions and the well-documented pernicious health effects of these, ‘just focusing on growth’ is a dangerous approach. It could also prove disastrous if the additional pollution triggers irreversible ecological damage, potentially limiting future growth and further immiserating the most vulnerable populations.

Going forward

To the extent that the EKC finding shows that countries can continue to grow without seeing ever increasing pollution levels, it should provide a hopeful message for developing countries. But as has been argued here, the finding should not be seen as a solution in itself, particularly in the short term. Policy can and should play a central role in minimising the environmental costs of economic growth.

Indeed, some economists are optimistic – Dasgupta et al. (2002) argue that by using the right policy instruments, developing countries could experience both ‘lower and flatter’ EKC curves than their wealthier counterparts. Although developing countries face serious barriers to enforcing environmental regulations, new research suggests that simple interventions can be surprisingly effective (see, for example the IGC’s research on the effects of firm transparency on pollution). Time to get to work.

Editor's Note: This blog post is linked to the LSE Festival: New World (Dis)Orders

References

Cole, M. A. & Neumayer, E. (2005). Environmental policy and the environmental Kuznets curve: can developing countries escape the detrimental consequences of economic growth?, In P. Dauvergne (Ed.), International Handbook of Environmental Politics, 298-318, Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Cole, M. A., Rayner, A. J. & Bates, J. M. (1997). “The Environmental Kuznets Curve: An Empirical Analysis”, Environment and Development Economics, 2: 401- 416.

Dasgupta, S., Laplante, B., Wang, H. & Wheeler, D. (2002). “Confronting the Environmental Kuznets Curve”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(1): 147-168.

Grossman, G. M. & Krueger, A. B. (1991). “Environmental impacts of the North American Free Trade Agreement”, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), (Ed.), Working paper 3914.

Grossman, G. M. & Krueger, A. B. (1995). “Economic Growth and the Environment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(2): 353-377.

Kuznets, S. (1955). “Economic Growth and Income Inequality”, The American Economic Review, 49(1-28).

Levinson, A. (2009), “Technology, International Trade, and Pollution from U.S. Manufacturing”, The American Economic Review, 99(5): 2177–92.

Levinson, A. & O’Brien, J. (2015). “Environmental Engel Curves”, Working paper 20914, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Shafik, N. (1994). Economic Development and Environmental Quality: An Econometric Analysis, Oxford Economic Papers, 46(5): 757-773.

Stern, D. I. & Common, M. S. (2001). “Is there an environmental Kuznets curve for sulfur?”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 41(162- 178).

World Bank (1992). World Development Report, New York: Oxford University Press.