Learning to teach by learning to learn: Measuring the effects of an innovative teacher training programme in Uganda

In 2007, Uganda became the first African country to introduce free universal secondary education. Yet, in 2017, 79% of students who began primary school, which is also free, did not make it to secondary school at all.[1] How can the delivery of education be improved to address this issue?A unique teacher training programme in Uganda has begun and is providing significant insight into overcoming the challenges of retaining children in education.

Experts highlight how low teacher morale, an emphasis on rote-learning (a memorisation technique based on repetition), and a syllabus divorced from real-life applications all combine to create an environment in which students do not see the value of staying in school. What approaches can be implemented that transform these fundamental components of education systems to ensure that learning becomes a life-long endeavour that facilitates the development process?

Learning to teach by learning to learn: Increasing capacity for scientific inquiry

Kimanya Ng’eyo Foundation for Science and Education (“KN”), founded in 2007, is a Ugandan NGO that, since 2014, has been working with education officials to run a teacher training programme. Unlike most such programmes that provide teachers with particular content, incentives, or pedagogical techniques, KN aims to nurture a love of learning in all their programme participants. Their objective is to re-invigorate the intrinsic motivation of teachers and to help them to cultivate a similar love of learning about the world among their own students. KN’s programme does this in two main ways.

First, the content they use helps teachers internalise how basic scientific capabilities, and methods of scientific inquiry, can be used to address social issues in their local communities that go far beyond the classroom. Second, their mode of content-delivery breaks the teacher-student hierarchy, creating a classroom environment in which teachers and students participate as equals united by a desire to learn and discover systems and processes in the world around them. In this new environment, the teacher mimics and then internalises approaches to learning that they experience themselves. They constantly ask students to explain, in their own words, what they have understood. These lessons often utilise teaching aids from the local environment that students are familiar with in order to weave theoretical and practical learning together in a manner that connects knowledge to its local applications. In this way, knowledge is not transferred from teacher to student, but discovered by the student with the teacher’s guidance.

We are working with KN to study the effects of their innovative programme

Our research is studying whether KN’s methods are effective at addressing our motivating questions: can the programme motivate teachers to invest more in their profession? If so, will it increase student learning and ability to continue through the schooling system? We initially wanted to work with KN because we saw a number of very promising signs in our interactions with them. In early 2017, the programme was in high demand by teachers, with 282 teachers in 60 schools across Central Uganda offered the training between 2014 and 2017. When we spoke with some of them, they seemed to have been re-invigorated by their experience. Both they and their students spoke about how their classroom environment had been transformed.

In fact, the effects went far beyond the classroom. In some communities, teachers embraced KN’s emphasis on applying scientific principles to local issues, making major changes to their agricultural practices by experimenting with new methods and techniques. One teacher we talked to became such a productive gardener that she shifted from being a net-consumer to a net-producer who finances the education of three secondary-school students and is investing in the construction of her own home. She has also become a key source of guidance and insight to members of the community, whereas in the past she viewed regular interactions with community members as unbecoming of her social status. Both we, and the Ministry of Education and Sports of Uganda, were eager to better understand the degree to which this transformation can be attributed to KN’s training.

To go beyond these promising anecdotes, we need numbers. Supported by IGC Uganda, and in collaboration with both KN and the Ministry of Education and Sports, we were able to collect data on a number of key aspects relating to KN’s impact. This process is still on-going, but results so far are highly encouraging. As we show in Figure 1 below, we find that the training is associated with major shifts in teacher attitudes, improvements in school retention rates, and higher test scores.

Surveys of the teachers show major shifts in attitude after participating in the programme

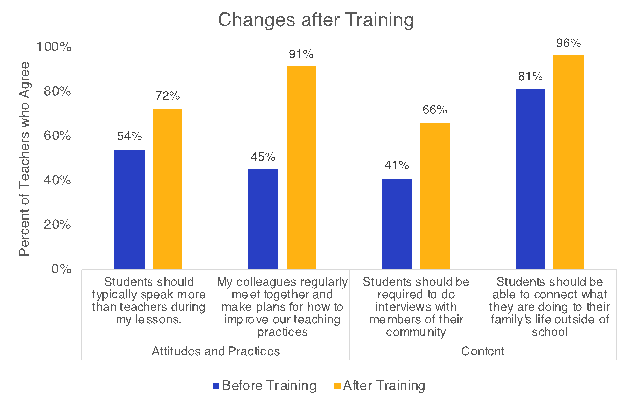

Figure 1

Figure 1

KN asked teachers about their views on key attitudes and teaching practices both before and after the training. Comparing these, we observe major shifts in these views. For example, with regard to attitudes, before the training 54% of teachers agreed with the statement that students should typically speak more than teachers. After the training, this increased to 72%. KN’s focus on teaching locally-relevant content had a visible effect: the share of teachers who viewed it as important that students conduct interviews with members of their community increased from 41% to 66%. Perhaps most importantly, teacher morale and commitment seem to have been greatly improved – the share of teachers who report regular meetings among colleagues to discuss plans to improve their teaching doubled, increasing from 45% to 91%. Across these, and many other attitude measures, we observe large, positive, and statistically significant effects.

Schools with teachers attending the programme have significantly greater retention rates

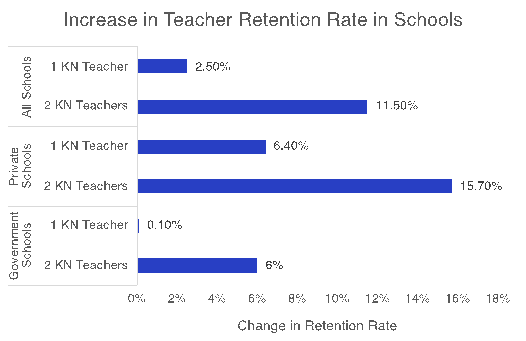

The Ministry of Education and Sports provided us with data on 128 schools from their central database on teacher retention rates. Teacher retention is a very important issue in Uganda. In our data, the average school retains less than half of its teachers in any given year. Retention rates are increasing in general among our schools, which means that we cannot simply do a before-after training comparison. Instead, we measured whether the increase over time was larger in KN schools than in similar non-KN schools, effectively treating the non-KN schools as a control group. Our results are presented in Figure 2 below. We found that schools with at least two teachers trained see retention increase by an additional 12 percentage points on average, which is substantial when compared to the average of less than half. Furthermore, this effect was especially large – at 16 percentage points – for private schools, where retention rates and teacher motivation are particularly low.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Students in classes where the teacher attended the programme have higher test scores

We also worked with three large schools to digitise test scores across a variety of subjects and classes in order to see if the new teaching practices translate into real learning. Our basic strategy was to compare the test scores of classes with KN-trained teachers with those of classes of the same subject, in the same term and at the same school, with teachers not trained by KN. For example, were test scores higher in the grade five maths class taught by a KN-trained teacher than in the grade five maths class taught by a different teacher? The answer is a resounding yes. The KN classes scored between 0.34 and 0.42 standard deviations higher on average. To put this number into context, an effect of 0.2 standard deviations is normally considered to be large by education specialists.

We were also careful to check that this was not simply because KN attracts teachers that are already highly skilled. In fact, we find that prior to the programme these teachers were actually achieving lower scores on average, which suggests that this alternative explanation is unlikely. More generally, we ran a number of checks of this kind, and the results suggest that our measured effects really did come from KN training helping teachers to improve the scores of their students.

Our conclusion: positive suggestive results, and a much more detailed investigation is currently underway

All in all, our results to date suggest that KN’s novel teacher training can have a number of positive effects within the Ugandan schooling system. This may be a key factor in addressing the issues of student dropout and the lack of transition into secondary school. However, our research is only at an early stage, and results are very preliminary. To this end, we are now testing the programme in a fully rigorous manner by running a randomised controlled trial. Across three districts in Uganda, we are working with a large number of schools, where a randomly selected half will receive KN’s training, and the other half will serve as a control group. We can then measure whether differences emerge between these two groups of schools over the medium and longer term. The trial began in January 2018, with the first major set of results due around August 2020. We greatly look forward to sharing the results with policymakers and wider audiences in Uganda and beyond.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number (1809427). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

References

UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2018), “Uganda education and literacy: Progress and completion in education.” Retrievable at http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/ug

[1] UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2018), “Uganda education and literacy: Progress and completion in education.” Retrievable at http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/ug.